By Ray Bennett

LONDON – Roger Moore, who died on May 23 aged 89, told me that really he was a frustrated bank robber. “It’s only fear that’s stopped me from robbing banks, and that’s why I’m a movie actor. I’d get caught. I’ve never been caught acting.”

I spoke to him at Pinewood Studios on Dec. 10, 1984, on the set of his last James Bond picture, “A View to a Kill”. He had just been shooting an action scene with co-star Tanya Roberts. Unruffled, he sat on a director’s chair in the middle of a very cold soundstage smoking the first of several Davidoff cigars he would enjoy through the day.

“The boilers are gone. This centre of the British film industry on a Monday morning is freeze-your-bollocks-off time.”

The debonair star did not look it, but he was 57 years old at the time and so I asked if there would be an eighth 007 outing for him.

“The answer is always the same,” he said. “No.”

“Until it’s yes,” I said.

“Until it’s yes. One thing you can be sure about me is that I always tell the truth until I open my mouth. Then, I lie.”

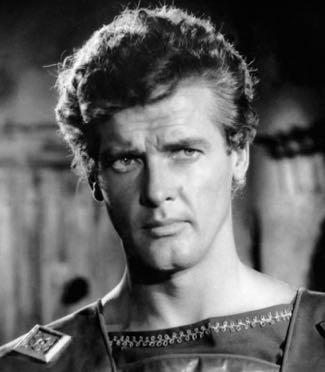

As it turned out, “A View to a Kill” (above) was Moore’s final appearance as James Bond so I was pleased to catch him before it all ended. I spent the best part of an hour talking to the star who had been famous in the United Kingdom since the Fifties when he picked up a sword in the title role of the TV series “Ivanhoe” (pictured below).

Signed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in the mid-Fifties, he made a clutch of Hollywood pictures without huge success: “The Last Time I Saw Paris” (1954) starring Elizabeth Taylor and Van Johnson, “Interrupted Melody” (1955) starring Glenn Ford and Eleanor Parker, “The King’s Thief” (1955) starring Ann Blyth and David Niven and “Diane” (1956) starring Lana Turner.

Signed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in the mid-Fifties, he made a clutch of Hollywood pictures without huge success: “The Last Time I Saw Paris” (1954) starring Elizabeth Taylor and Van Johnson, “Interrupted Melody” (1955) starring Glenn Ford and Eleanor Parker, “The King’s Thief” (1955) starring Ann Blyth and David Niven and “Diane” (1956) starring Lana Turner.

Television proved more fruitful and right after 39 episodes of “Ivanhoe” (1959-60), Moore dug for gold in “The Alaskans” with Dorothy Provine and took over from James Garner in “Maverick” for 16 shows.

Moore told me: “‘The Alaskans’ was almost a Western: a frozen Western. I didn’t want to do ‘Maverick’ at all. I didn’t want to replace Jim Garner (pictured below with Moore). They said I wasn’t replacing him, that it was an entirely different character [cousin Beauregard] but I noticed all the trousers had J. Garner written inside.”

It was about that time that I saw a quote in which Moore said he always blinked when guns went off. I asked him how he’d gotten over it.

“I haven’t,” he said. “Everybody blinks, actually. You see Western stars, they’re always squinting their eyes. That’s because they’re pinching the muscles to stop themselves from blinking. The trouble with me is that I blink before it goes off because I know it’s going to go off. But there you are. I’m getting better.”

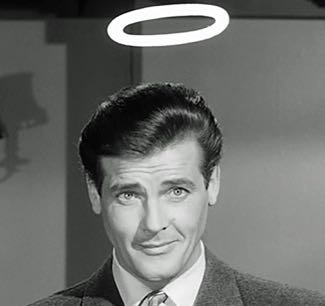

Moore hit pay dirt as the suave and ruthless Simon Templar in ITC’s hit series “The Saint” (below left), which ran for 118 episodes from 1962 to 1969. He was fairly used to replacing people, he said: “George Sanders played ‘The Saint’ long before me. Louis Hayward did, too, and Hugh Sinclair, an English actor, in some films. People said Tom Conway also did but he didn’t. He played ‘The Falcon’, a lift from ‘The Saint’.”

By the time that series finished its run, Sean Connery had made five James Bond films and it looked as if he would finally quit the role. Almost everyone agreed that Roger Moore was the natural choice to take over. I asked him if it had been that simple. “Well, I don’t suppose anybody else worked as cheap as me or turned up on time,” he said.

In fact, he had been asked to play Bond earlier when it appeared that Connery would leave. Moore said he discussed one project as 007 but it was set in Cambodia and events made it impossible to shoot there so the story was dropped. The Bond producers went on to another one and by that time Moore had decided to do ‘The Persuaders’ with Tony Curtis on TV. “Sean went back and did another one and when he finally took a powder, they came back to me. I have no pride whatsoever. Always ready.”

In fact, he had been asked to play Bond earlier when it appeared that Connery would leave. Moore said he discussed one project as 007 but it was set in Cambodia and events made it impossible to shoot there so the story was dropped. The Bond producers went on to another one and by that time Moore had decided to do ‘The Persuaders’ with Tony Curtis on TV. “Sean went back and did another one and when he finally took a powder, they came back to me. I have no pride whatsoever. Always ready.”

Moore’s first appearance in the role was in “Live and Let Die” (1963) and it was a very different James Bond as he continued to show in “The Man With the Golden Gun” (1974), “The Spy Who Loved Me” (1977), “Moonraker” (1979”, “For Your Eyes Only” (1981) and “Octopussy” (top, 1983).

I suggested to him that he played the character much more as the man I saw in Ian Fleming’s novels, very much from the playing fields of England as a man who often got into trouble but was always able to get out of it.

“No. I’ve never gone back to the books to find out what it’s all about. I just play it the way I see it,” Moore said. “I always want humour in the films. ‘The Spy Who Loved Me’ (below), I think, had all the right ingredients in it. ‘Octopussy’ worked, too, in terms of the humour that I tried to get in. A lot of the time, it’s impossible to get any humour in. There are moments when you have to be serious and they’re the moments when I really want to laugh my head off. You think, ‘This is a load of cobblers.’”

Was it really a tussle to introduce humour into the films? “Well, no, not a tussle. Sometimes, it’s written in the script, sometimes it’s not there at all. Whoever’s directing, John Glen*, say, or in the past Lewis Gilbert*, would say, ‘Come on, then, let’s have a joke here.’ Or I’ll say I think we need a joke. Then we make them up. Even if they’re written, we change them. As Cubby Broccoli always says, ‘Bonds are made by committee.’ We basically all work together to make it the best we possibly can and then it’s up to the director to adjudicate what he things is best.”

When “Octopussy” (below) came out in 1983, Sean Connery returned to Bond in a remake of “Thunderball” titled “Never Say Never Again”. That wasn’t a problem, Moore said: “I was delighted! Everybody’s working. Making two films at the same time, you double the amount of people who have work. Cubby, of course, was pissed off but it didn’t worry me.”

I asked about Christopher Walken, the villain in “A View to a Kill”: “Lovely fella. Very interesting. Good actor. Very pleasant to work with too. Mind you, all my villains that I’ve had in Bond have been very good. I envy them all because they’ve got the best part. They really do. Bloody villains!”

In the centre of the Pinewood soundstage, an assistant director approached us, “Roger, when you’re ready?”

Moore said, “When I’m ready? I’m not ready. I don’t want to go. Oh, well. Excuse me.”

He did a fight scene in three sides of a hotel room and after a few takes, it was time for lunch. Moore ate along with everyone else in the studio commissary sitting with his son Christian and Dudley Moore, who was dressed as an elf because he was shooting “Santa Clause: The Movie” at the studio. My table was next to theirs.

After lunch, Roger Moore joined me again on the soundstage: “Did you have a good lunch?” he said. “Where did you eat? So. What were we talking of? What boring subject was I on about? Bond. Yes. Bond and boredom. Yes.”

Mick Jagger had said recently that it was odd to be a rock star at 40 so I asked Moore if he felt it was odd to be an action hero at his age: “I dunno. I play heroes, you know? Sometimes I jump around; sometimes I don’t. The last movie I made, I got the shit kicked out of me. I was the hero but he was not an athletic hero.”

That was “The Naked Face” (above, 1984), written and directed by Bryan Forbes and based on the first thriller written by Sidney Sheldon. Moore played a psychiatrist suspected of murdering one of his patients. Was that a stretch? “Well, Bond doesn’t say much, you know? Playing a psychiatrist, you listen a lot but you also have a lot to say. But in no way is he a hero. When he finally gets the shit kicked out of him, there’s very little to do about it, which made a change.”

Was it a risk for him to play a villain? “It depends. You know, leading film actors have a persona when they play heroes so there are things they don’t do. I would love to play villains but they won’t let me. Nobody casts me as a villain. In a certain sense I can see why. There are people who go to see you for the type of thing you do and you might piss them off by being nasty. But being rotten, they’re the best parts. That would be natural to me. This is acting. Being a nice guy is acting because really underneath, I’m a shit.”

“Tell me more about that,” I said. “Exactly what is the truth underneath this charming exterior?” Moore said: “A monster! A monster!”

Was there a moment, in fact, when he became aware that he had the kind of good lucks and charm that made people like him?

“Well, by answering that question it means that I accept what you’ve said and, of course, how right you are. Er, no. I don’t think so. I’ve always been rather surprised, actually, that I was employed. I didn’t expect not to be employed but I’m always surprised when I am. I’ve been very lucky. It’s luck in the first place to be there at the right time. It’s luck that the part comes along. It’s luck that you’re accepted in it. It’s luck that they come back for more. And it’s their bad luck because they’ve got to watch it.”

Was it ever a worry that audiences would be unwilling to accept him in other roles? “No, it’s no worry. I’ve always had that question asked ever since I did things that I became known in, you know, things like ‘Ivanhoe’. I finished ‘Ivanhoe’ and went to Warner Bros. and made some movies there and a couple of TV series and I was not afraid I would be stuck there. I’ve been lucky. I’ve been able to move back and forth from TV to movies.”

I suggested that he’s one of those actors whose work is described as effortless. Did he resent that?

“No,” he said. “That’s the way it should be.”

But did he feel he was not given credit for the hard work that makes it appear easy?

“I don’t give a shit. I get paid. If acting shows onscreen then it’s wrong. Film acting is listening and re-acting. Unless, of course, you’re playing what I call the lovely character parts where you wear a false nose and beard and hide behind things. As a leading man, you have no physical things to hide behind. You haven’t got the hump, you know? You can’t do, ‘The bells! The bells!’, all that crap. Which is fun, you know, fun to do.”

Had he ever wished his career had gone in other directions. “I would be an ingrate, if I did,” he said. “It’s about those crossroads you come to in life. At the beginning of my film career, literally within the same week as I signed for MGM, I was offered The Old Vic. Well, I might have gone on carrying a spear for 40 years or I might have gone on to be a classical actor. Who knows? I have a feeling I’d have been carrying a fucking spear. But I only say things like that because I’m modest.”

As it was, Moore’s career brought fame and riches and he was grateful for both. “The joy of having money is that you can give your children what you want to,” he said. “Financial security is a great state. I used to have ulcers but I’ve noticed since I have no financial worries to speak of that I don’t have ulcers any more.”

Had he ever been flat broke?

“Oh, sure, but I hate doing a story like, ‘Oh, god, you have no idea how I suffered.’ Bullshit! But, yeah, I wasn’t born rich. I’ve always had to work. Our profession is very dodgy and I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone. Quite often you get asked what advice you’d give to young people who want to go into acting and I say, ‘You’ve really got to like it. You’ve really got to be prepared not to have any success and put up with an awful lot of crap from people dropping it on you from great heights. Because even when you’re lucky enough to become successful, they’re still dropping it on you. And they’re trying to to knock away the rungs on the ladder underneath you. The first ones are the critics who love to hate you. I would have made an ideal critic. I can be as rude about myself as critics are. And I can be even ruder about them.”

Moore’s humour was always self-deprecating and I suggested that was borne of a great deal of self-confidence.

He smiled, “I presume so. Obviously. I must be self-confident to say this. You see through me.”

Was there a time when he lack that self-confidence? “Oh, yes. I used to be terribly timid. I would rather not eat than go into a restaurant on my own. Even now, I hate that. I sort of covered up my timidity by being ingratiatingly charming. Which is why I got away with murder with teachers at school. Smiled a lot. I recall when I came out of the army and started in repertory, a director, or producer as we used to call them, said, ‘You’re not very good. Smile a lot when you come on.’ So, I smile a lot.”

Was it hard to muster the same energy for a new Bond? “Well, no,” he said. “It’s the same as doing any new picture because there’s a new script, a new cast. It’s usually most of the same crew but most of the pictures I do are with the same crew anyway. They’re the only ones who will work with me.”

In fact, Moore made other entertaining films in between 007 outings including George S. Cosmatos’s World War II adventure “Escape to Athena” (1979) and “Shout at the Devil” (1976) by Peter Hunt, who had edited and directed an episode of “The Persuaders”, edited three Connery Bonds – “Dr. No” (1962), “From Russia with Love” (1963) and “Goldfinger (1964) – and directed “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service” (1969) with George Lazenby as the secret agent.

His co-star in “Shout at the Devil”, set during World War I, was Lee Marvin (pictured above). “I loved working with Lee,” Moore said. “A great character. He’s rich; a fruity actor. There’s a lot going on there.”

I mentioned that I had recently interviewed American director Andrew V. McLaglen, with whom Moore had made three films: “The Wild Geese” (1978) with Richard Burton and Richard Harris, “Ffolkes” (1980 a.k.a. “North Sea Hijack”) with James Mason and Anthony Perkins, and “The Sea Wolves” (1980) with Gregory Peck and David Niven.

“Oh, Andy is a lovely fellow,” Moore said. “I’d love to do another with him. He’s great, a beaut to work with. I mean, bang! He’s a wonderful man. He says, ‘They think there’s something wrong with me as a director in Hollywood because I bring movies in on time.’ And he does. He just drives it through. He’s really good. A funny fellow, too.”

Moore was already friends with Peck and Niven: “Working together was our idea. ‘Sea Wolves’ was great fun to do because there was a bunch of mates such as Trevor Howard (pictured above with Peck, Moore and Niven) and Patrick MacNee.” He lived in Switzerland, he said, because David Niven, who had died in 1983, invited him to visit and he decided to stay.

“Miss him,” Moore said.

I told him that a colleague and I had been promised an interview with Niven many years earlier but through no fault of his own he had to cancel it at the last minute. He told us, “Write anything you like, I’ll swear I said it.”

“Ha!” said Moore. “Typically David.”

I asked if he, Connery and Michael Caine, contemporary movie spies, really were mates: “Oh, yes. Ours is a very small profession and actors are inclined to congregate together. At one time, when Michael and I were both very stable and Sean was here, all three of us would see one another a lot. Now, it’s when we happen to be in the same place. I probably see Sean more in California than I do here because I go there to rest.”

The Bond films are famously international so I asked if he enjoyed all the travelling: “I’m fed up with travelling,” he said. “I think I’m going to become a hermit and not move anymore. This week, I had a few days off. Every weekend, I go home to Switzerland, which is only an hour and a half’s flight but there’s the two-hour drive at the other end and you’ve always got that 45 minutes to be at an airport. Then, on Tuesday we went to Paris. On Friday, to Amsterdam. Then yesterday back in London. I mean, phew! But that wasn’t for work. It was because I had a few days off so it’s my own damned fault!”

Our time together was coming to an end but I wanted to know if he had strong political views.

“Hmmm,” he said.

Did he care to talk about them?

“I avoid expressing them,” he said, “I’m slightly to the right of Attila the Hun, that’s all. If everybody knew my views, I’d make a lot of enemies. I believe in dictatorship as long as I’m the dictator. A benevolent dictatorship. I suppose I started off, as most young people do when they start thinking of politics, they’re communists. Then you become socialist. Then Labour. Then Liberal when you don’t know which fucking direction you’re going, and then you end up being Conservative.”

The A.D. came over to fetch Moore and our time was over.

“Excuse me,” he said. “You can make up the rest, as David said. What I like, I’ll take credit for. What I don’t, I’ll deny.”

*John Glen, now 85, directed the Bond films “For Your Eyes Only” (1981), “Octopussy” (1983), and “A View to a Kill” (1985) with Moore and “The Living Daylights” (1987) and “Licence to Kill” (1989) with Timothy Dalton as 007. He edited “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service”, “The Spy Who Loved Me” and “Moonraker” (1979) as well as Moore’s films, “Gold” (1974), “The Wild Geese” and “Sea Wolves”. Lewis Gilbert, now 97, directed “You Only Live Twice” (1967) with Connery and “The Spy Who Loved Me” and “Moonraker” with Moore. His other films included “Reach for the Sky” (1956), “Sink the Bismarck!” (1960), “Alfie” (1966), “Educating Rita” (1983) and “Shirley Valentine” (1989).

A version of this story appeared in the Bigscreen section of TV Guide Canada in June 1985.