By Ray Bennett

LONDON – The New York Times critics have named their choices of the best movies of the 21st century so far. They include titles such as “I’m Not There”, “L’Enfant” and “The 40-Year Old Virgin” but ignore fine films such as “Arrival”, “The Grand Budapest Hotel” and “Inception”.

Any such list is, of course, subjective. We all can think of great films overlooked but here, in alphabetical order, are 20 more films that for me have been highlights of the century so far. All are available on Blu-ray and/or DVD except “The Sun Also Rises”.

12

Russian filmmaker Nikita Mikhalkov’s film version (pictured above) of Reginald Rose’s fine play “12 Angry Men”, which screened in competition at the 2007 Venice International Film Festival, takes the basic plot of a dozen jurors who must decide the fate of an accused murderer and expands it into an examination of modern Russia. The essential debate about democratic justice and all of the suspense remains, but the defendant is a Chechen youth charged with killing his Russian stepfather. That permits an illuminating exploration of the post-Soviet era as each juror reveals his background, life choices and prejudices. Eduard Artemev’s score adds all the right touches.

All is Lost

Robert Redford (pictured above) gives a career-best performance as a man alone in peril aboard a sailing craft in the Indian Ocean in J. C. Chandor’s first-class 2013 thriller. A voice-over at the start speaks of doom and regret and the film flashes back to eight days earlier when the man awakens in the cabin of his sailboat to discover water flooding in from a hole made by a freight container that has fallen from a container ship. With extraordinary intensity, the film relates the man’s attempts to save his boat and himself. Alex Ebert robust music won the Golden Globe for best original score.

Apocalypto

Not for those for whom Mel Gibson can do no right and not for anyone who hates excessive violence, but this full-tilt 2006 thriller (pictured above) is a masterpiece of pace and excitement. It’s a pure chase movie set in a roughly pre-Columbian time where Mayan rulers wreak gut-churning horror on anyone they choose. With barely any dialogue, the film follows a young man named Jaguar Paw (Rudy Youngblood) who lives a simple life with his young family in the forest. That ends when blood-thirsty warriors descend on their home, killing at random and taking away women and children for who knows what fate. Paw sets out to save them. It’s ferocious stuff and definitely not for the squeamish but the director manages to place the violence in a place and time where it is plausible. Major contributions by cinematographer Dean Semier, editor John Wright and composer James Horner.

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford

Easily my choice as best film of 2007 Andrew Dominik’s elegiac and epic Western is elegant, detailed and profound. Dominik’s screenplay, adapted from a splendid novel by Ron Hansen, offers rich opportunities to a fine cast. Brad Pitt (pictured above and top), who was named best actor at the Venice film festival, plays Jesse James with Casey Affleck as Robert Ford. The film has an evocative production design by Patricia Norris, beautiful images by cinematographer Roger Deakins and expert editing by Curtiss Clayton and Dylan Tichenor. Music and songs by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis add to the often plangent mood. More than a Western, it’s an examination of envy and the dangers of fame.

The Band’s Visit

Eran Kolirin’s little 2007 gem is a delightful movie that tells a simple tale of a group of dignified Egyptian musicians on a trip to Israel who end up in the wrong town but encounter a night of magic. Starring Sasson Gabai and Ronit Elkabetz (pictured above), it’s smart and tender, and filled with small moments of high comedy. Spry and laced with understated wisdom, it’s a glorious road show that posits larger themes not only about the relations between the countries but also of mankind. It does so with such deferential grace and good humour that the grandness of the themes never gets in the way of an entertaining scenario underscored with droll comedy and counterpointed with unexpected revelations. Habib Shadah’s score enhances the changing moods.

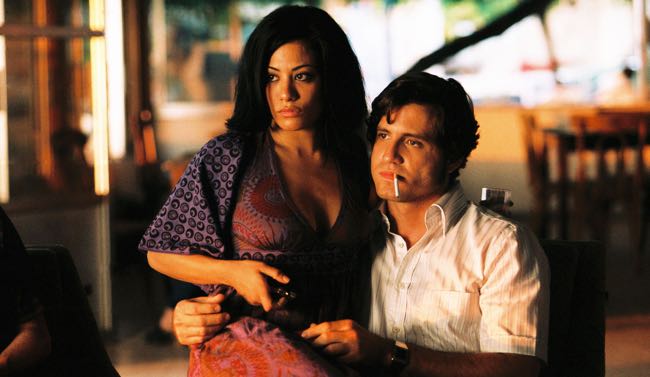

Carlos

Epic depiction by French director Olivier Assayas of the life of the international terrorist known as Carlos the Jackal shot in three parts for television with all 5 hours and 33 minutes screened in full at the 2010 Festival de Cannes. It is a tremendous achievement that shines a light on the way many countries use criminals to further their domestic and international goals. Politically informative, it also offers great drama with excitement and suspense, and no little tragedy. Assayas and his cast bring the huge number of characters to life, and in Venezuelan actor Edgar Ramirez (above right) he found a performer who captures the Carlos’s enormous ego, considerable charm and manifest criminality.

Children of Men

In his gripping 2006 thriller “Children of Men,” director Alfonso Cuaron takes the classic movie formula of a cynical tough guy required to see an innocent party to safe harbour and shoots it to pieces. Set in 2027, with the world gone to hell in a hand basket, the film paints a bleak portrait of a future in which complete global human infertility has meant that no babies have been born anywhere in 18 years. Cuaron and co-scripter Timothy J. Sexton do the important little things that help make characters believable and take sufficient time to register the deeper impact of things that are troubling the world. John Taverner’s score echoes those themes smartly. Michael Caine, Peter Mullan and Julianne Moore (pictured above with Owen) add vivid cameos. Owen carries the film more in the tradition of a Jimmy Stewart or Henry Fonda than a Clint Eastwood or Harrison Ford.

The Constant Gardener

John Le Carré’s terrific novel is adapted by Jeffrey Caine for a tense, exciting and profoundly disturbing 2006 thriller directed by Brazil’s Fernando Meirelles. Ralph Fiennes plays a mild-mannered, garden-tending British diplomat stationed in Kenya where his beautiful activist wife (Rachel Weisz) gets into serious trouble when she tries to expose the corruption of big pharmaceutical companies exploiting the country. Her violent death sparks him into action as he tries not only to solve her murder but reveal collusion between the U.K. authorities and the drugs firms. Fiennes and Weisz (who won the Academy Award as best supporting actress) are outstanding with fine support from a cast that includes Hubert Koundé, Danny Huston, Bill Nighy and Gerald McSorley. Production designer Mark Tildesley and cinematographer César Charlone take full advantage of the colourful locations enhanced by a typically insightful score by Alberto Iglesias.

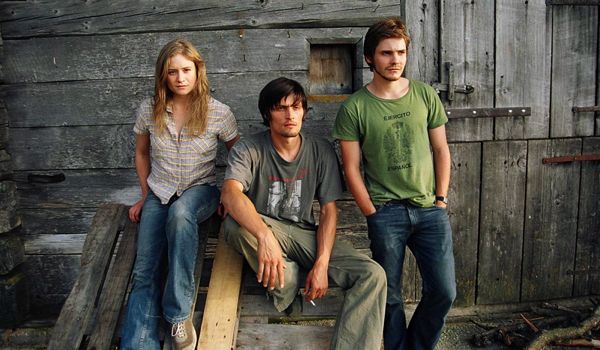

The Edukators

That rare beast, a terrific movie that boasts intelligent wit, expert storytelling, delightful characters, and grown-up dialogue plus suspense and a wicked surprise ending. Directed and co-written by Hans Weingartner, the 2004 German-language film’s ambition is high as it grafts all the elements of a thriller onto a fascinating discussion of the need for kids to rebel. Daniel Bruhl, Stipe Erceg and Julia Jentsch play students who take their politics seriously but feel they have no voice. With a membership list from the city’s yacht club, they break into rich homes where they they stack furniture, put objets d’art in the toilet, toss the couch into the pool and stick the stereo in the fridge. They leave a note: “Your days of plenty are numbered,” signed The Edukators. It goes horribly wrong when a home owner surprises them. They panic and kidnap him but he turns out to be far from what they expected. Smart and sophisticated, it’s a thriller that, along with Andreas Wodraschke’s music, will leave you smiling.

Happy-Go-Lucky

No one expects confection from British sobersides Mike Leigh and so his light-as-air film “Happy-Go-Lucky” is as surprising as it is delicious with an indelible performance by Sally Hawkins (pictured above), who was named best actress at the 2008 Berlin International Film Festival. Her performance divided audiences but to me she is a marvel with her urchin looks and irresistible smile. She plays an irrepressibly cheerful, smart, confident and goofball but caring primary school teacher named Poppy. There’s no plot to speak of as it’s just a snapshot of Poppy at work being watchful of her flock, at home with her friends and family, and at play with the world. Darkness appears in the form of a pupil abused at home and a disturbed driving instructor (Eddie Marson) who becomes infatuated with her, both of which test Poppy’s eternal optimism. Gary Yershon’s playful music adds to the pleasing mood of a lovable film, which shares Poppy’s optimism without being syrupy or sentimental.

I Served the King of England

Forty years after their “Closely Watched Trains” won the Oscar for best foreign-language film, director Jiri Menzel in 2007 adapted another novel by the late Bohumil Hrabal, one with a similar sensibility. It’s a picaresque tale of an ambitious but naive Czech waiter whose gumption, opportunism and blinkered awareness of events see him thrive amid political and social upheaval. The film begins with a grizzled, aging Jan Dite (Oldrich Kaiser) released after 15 years in a Czech prison and flashbacks tell how the fates have conspired to bring him to this pretty pass. Ivan Barnev (pictured above) is sublime as the young man, gifted with the physical grace of great comedians and with expressive features that encourage sympathy despite some of the unsympathetic things he does. It’s a saga told sumptuously of childlike wonder in the face of dark corruption and war, mixing high comedy, surreal sequences and genuine drama viewed from a wise, jaundiced perspective. Its all accompanied by Czech composer Ales Brezina’s savvy score.

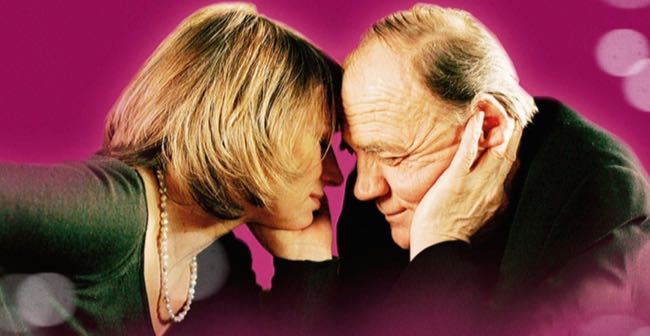

Julia’s Disappearance

Sophisticated and insightful, Swiss director Christoph Schaub’s German-language comedy “Julia’s Disappearance” is a romantic comedy based on the feeling that as people get older they become invisible to others. Corinna Harfouch plays Julia, a cultured and beautiful woman who is anxious about her 50th birthday party where friends are waiting to celebrate the milestone. She delays her arrival not least because of a chance meeting in a department store with a charming man played by Bruno Ganz (pictured above with Harfouch), who gives a master-class in the art of seduction. While Julia and her stranger dally over drinks, her colourful friends discuss the various pains and pleasures of getting older with sharp dialogue and great timing. Several strands are interwoven cleverly with warm and wry comedy. Balz Bachmann’s nimble score adds to the pleasure of a film that suggests getting older has its rewards and the days of pure screen romance are not a thing of the past. The film won the public award after its world premiere in the Piazza Grande at the 2008 Locarno International Film Festival.

Julietta

Pedro Almódovar’s sublime 2016 film “Julieta” is a reminder of how, in the hands of a master, a lifetime’s drama can be shown movingly and memorably in little more than an hour and a half of great cinema. It is sumptuous with great performances and a marvellous score by Alberto Iglesias. A tale of motherhood and loss drawn from short stories by Canadian Nobel Prize-winner Alice Munro in her 2004 collection “Runaway”, it follows a melancholy middle-aged teacher in Madrid named Julieta (Emma Suárez) as she reflects on her marriage to a romantic fisherman, Xoan (Daniel Grau), and their daughter, Antia, from whom she has been estranged for many years. Vivacious Adriana Ugarte (pictured above right with Inma Cuesta) plays the younger Julieta and together with Suárez they create an unforgettable character.

The Master

Paul Thomas Anderson’s complex and accomplished 2012 film “The Master” addresses the conflict between the puritan and hedonist traditions of the United States as it adjusts to its new potential and place in the world after World War II. The two extremes are exemplified in the characters of Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a self-righteous authoritarian founder of a quasi-mystical cult, and Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix, pictured above left with Hoffman), a self-interested flouter of authority in search of personal freedom. Their clash and recognition of the strengths and failings in each other that could be a mirror image form the basis of a film with no formal narrative arc, many strange happenings and an imponderable resolution. It is quite wonderful and boasts another typically fine performance by Amy Adams as Dodd’s implacable wife. Anderson’s regular composer Jonny Greenwood captures time and place evocatively.

The Piano Tuner of Earthquakes

Directed by the American Quay Brothers, this is a finely crafted 2005 horror film with a devious storyline and hauntingly beautiful production design that together are the stuff of nightmares. Integrating puppetry, animation and live action, the film (in Portuguese and English) has echoes of “Phantom of the Opera” and Jules Verne’s subterranean adventures. Terry Gilliam’s name on the credits as executive producer guarantees that it will appeal to those with a taste for something more than slightly twisted. The film is about vanity and pride, and the caging of beauty. Its elaborate fabrication has an intoxicating quality that captures the imagination like all good horror stories. British composer Christopher Slaski, who provides a suitably penetrating score, was named Best Young European Film Composer by the World Soundtrack Academy in 2009.

The Royal Tenenbaums

Splendidly enjoyable Wes Anderson 2001 saga about the weird and wonderful Tenenbaum family whose estranged patriarch (Hackman) returns to announce that he is soon to die. Anjelica Huston plays his former spouse with Ben Stiller, Gwyneth Paltrow and Luke Wilson as their offspring. The cast includes Owen Wilson, Bill Murray, Danny Glover, Seymour Cassel, Kumar Pallana and Alec Baldwin. Hackman is marvellous and the entire cast raise their game delightfully aided by an agile score by Mark Mothersbaugh.

The Sun Also Rises (Taiyang zhaocheng shengqi)

Fluid motion and glorious colours provide a visual treat in Jiang Wen’s sumptuous romantic fantasy, which screened in competition at the 2007 Venice International Film Festival. Flowers in bloom, intricately embroidered slippers, billowing curtains and a belly as soft as velvet are among the sensuous elements in a quartet of interrelated stories about characters who are variously addled, lecherous, vengeful and yearning in the four quadrants of China in the mid-1970s. Produced lavishly and shot imaginatively, the film is a delight for those who enjoy extravagantly gorgeous imagery without the violence that usually accompanies it. Besides being wonderful to look at, the film is great fun with sure-handed performances and Joe Hisaishi’s variegated score adds to the entertainment.

Synecdoche, New York

Oscar-winning screenwriter Charlie Kaufman’s first film as a director, “Synecdoche, New York,” mesmerises some and mystifies others, while some are bored silly. Philip Seymour Hoffman (pictured above left) is riveting as a theatre director who wins a lucrative genius award and decides to spend it on creating a synecdoche of his life as an ongoing drama staged in a vast building. Screened first at the Festival de Cannes in 2008, it has a dream-like quality but Kaufman says it’s not supposed to be a dream. It’s an otherworldly jigsaw puzzle of duplicated characters, multiple environments and shifting time frames. It requires concentration to stay up with all the changing characters and many abrupt moves in many directions. Many scenes are flat-out hilarious but the film has a deeply affecting aura of true melancholy. Mankind’s knowledge of death and the unknowable depths of other people’s minds are central to the story. Some sequences are simply there because it’s the movies and movies should be fun, but others are both poetic and profound, helped considerably by Jon Brion’s score.

Tulpan

Polished, funny and utterly charming, Kazakhstan director Sergey Dvortsevoy’s first feature film won the top prize in the Un Certain Regard sidebar at the 2008 Festival de Cannes. It tells of a family who not only endure but also relish the harsh life of sheep- and goat-herders on a barren landscape. Set on the bleak and windswept Hunger Steppe in southern Kazakhstan, 500 kilometres from the nearest city, it’s about a nomadic peasant existence that demands hard work from everyone with pleasures few and far between. The film’s universal story of conflict between generations and the way little eccentricities make life bearable with accessible humour makes it a delight.

Under the Skin

The vivid old Scots word “eldritch” could have been coined for Jonathan Glazer’s spooky 2014 film “Under the Skin” starring Scarlett Johansson (pictured above) as an alien on the prowl in Scotland. Based on Michael Faber’s frightening novel of the same name, it dispenses with much of the detail in the book to create an extraordinarily haunting mystery about the strangest of strangers in very strange land. Johansson is chilling as a creature in human form who tries hard to muster human warmth as she ventures out at night to cull young men as fodder for her fellow aliens whose activities, unlike in the fearful revelation of the novel, are never made clear. The result is hypnotic and unearthly. Glazer spurns the typical tropes of stories about aliens, ghoulies and ghosties with a relentless tone. The sometimes banal, and often startling images are from cinematographer Daniel Landin and there is an unsettling sound mix that blends eerily with Mica Levi’s disturbing score.

Here’s the New York times list

It’s going to be end of mine day, except before finish I am reading this great piece of writing to increase my knowledge.