By Ray Bennett

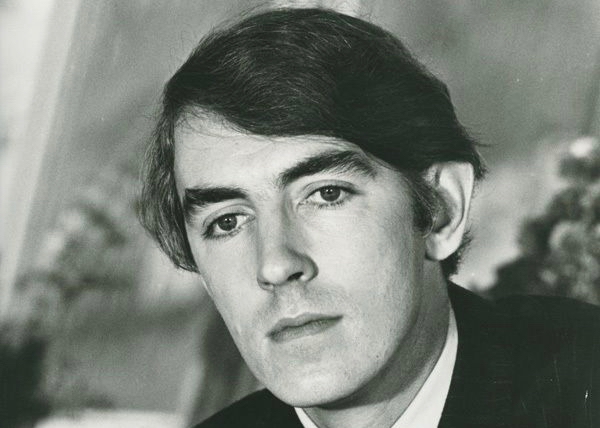

LONDON – Peter Cook, who died 25 years ago today aged 57, was the funniest person I ever saw and ever met. He was naturally, effortlessly funny but he was never ‘on’ in the way some comedians seem to always be performing.

He was famous for the Tony Award-winning stage shows ‘Beyond the Fringe’ (1962) and ‘Good Evening’ (1974), the much-loved British television series ‘Not Only … but Also’ (1965-70), and films such as ‘The Wrong Box’ (1966) and ‘Bedazzled’ (1967). But his legendary status in the U.K. derives from his many television appearances as a satirist in the Sixties and Seventies, the stage shows ‘The Secret Policeman’s Ball’ and ownership of the groundbreaking Establishment nightclub in London and the humour publication Private Eye.

I spent time with him in 1981 when he was in Los Angeles making a short-lived sitcom titled ‘The Two of Us’, an American version of Donald Sinden’s British Seventies comedy series ‘Two’s Company’. Relaxed and easy-going, he said he had never planned his career. “Career goals, or whatever they’re called? No, a number of things have happened obviously not by chance. I’ve written stuff and worked on stuff but I haven’t really thought of my life in terms of a career that has some peak to which it should aspire. Or any depths to which it should sink, for that matter. Or any plateau along which I should walk. It just seems to have gone along.”

He said he discovered he could be funny while at Cambridge University. “At school, I used to wander around doing stuff that led to catchphrases. Why this confidence was there, I don’t know but it was.” He started writing comedy professionally while still at university. He wrote the famous ‘One-legged Tarzan’ sketch at age 18 and sold it and several other sketches to Kenneth Williams for a West End review called ‘Pieces of Eight’. By the time ‘Beyond the Fringe’ came along, he was established and joined Jonathan Miller, Alan Bennett and Dudley Moore for the show at the Edinburgh Festival.

As to his influences, he said, “I’ve never quite known. I would say probably Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll and Spike Milligan would be the ones who sort of filtered through in some way and stayed. ‘The Goon Show’ had enormous influence among many others. Evelyn Waugh is my favourite writer.”

One of his regrets was that his screenplay based on Evelyn Waugh’s newspaper satire ‘Scoop’ was never filmed. “I would have loved to have done it. I was going to play William Boot. We updated it. Africa remains in turmoil and we introduced a new character, an American CIA man, the most unsuccessful CIA man they have who is thrown out of this small African state. He was called Charles Ivor Arlington with his initials on the luggage that his mother had given him. He was constantly trying to bug things and people. It was a good script. I was pleased with it but we couldn’t raise the money.”

Best of all, during our time together, over lunch at the Wine Bistro and in his dressing room at the CBS Radner Studios, was when he simply let his mind wander. We were talking about his sketches with Moore: “Whenever I see Dudley, we can get something going anytime, upper class or lower class, it just sort of flows out without any thought.”

He said he loved vague sort of upper class people: “Oh, do, do, do come in the … what do we call it, dear? … room, oh, room, yes. Sit down on the, ah, we get them in, man brings them up … chair! When we first bought this house, what did we have when we first bought this house? We had our whole life in front of us, that’s what we had. Well, we still have, of course, but there’s less of it now. I remember in the old days, I never thought about having my life in front of me or behind me. Always thought my life was just to left of me but apparently it wasn’t. It was in front of me. And tomorrow’s the last day of the rest of my life, is it? No, today is the first day of the month so you shouldn’t eat an oyster.”

I told him that my old friend, another Peter Cook, and I used to telephone people at random and see if we could start a conversation. He ran with it: “I thought I’d give you a ring because, you know, we haven’t talked for some time. In fact, we never ever have talked and I thought it was about time we established some sort of contact. Why? Well, I mean, if one starts asking why, one would never do anything. So I thought I’d give you a ring, ask how you are and, indeed, ask who you are. I have your name but that could be an alias. Do you spy for anybody? I’m in the pay of the Koreans at the moment. I have to go down to the fish market every Tuesday and look at the fish. I meet a little Chinese chap there. I give him a piece of paper and he gives me a piece of paper. Then I have to ring through to my, well, I wouldn’t call him my superior, I’ve never seen him. I only speak to him on the phone and give him some secrets about what’s going on. I have to make them up because the fellow I meet down at the fish market doesn’t speak a word of English. My sort of secrets are, well, they’re completely secret because I forget them as soon as I’ve been told them.”

Cook said he was “rather annoyed” at Cambridge when nobody asked him to become a spy: “Bit of an insult, really. I spoke French and German, fine material. The only trouble with being a spy is that you can’t talk about your work to anybody. You can’t come home to your wife and say, ‘I’ve toppled the leader of Ecuador.’”