By Ray Bennett

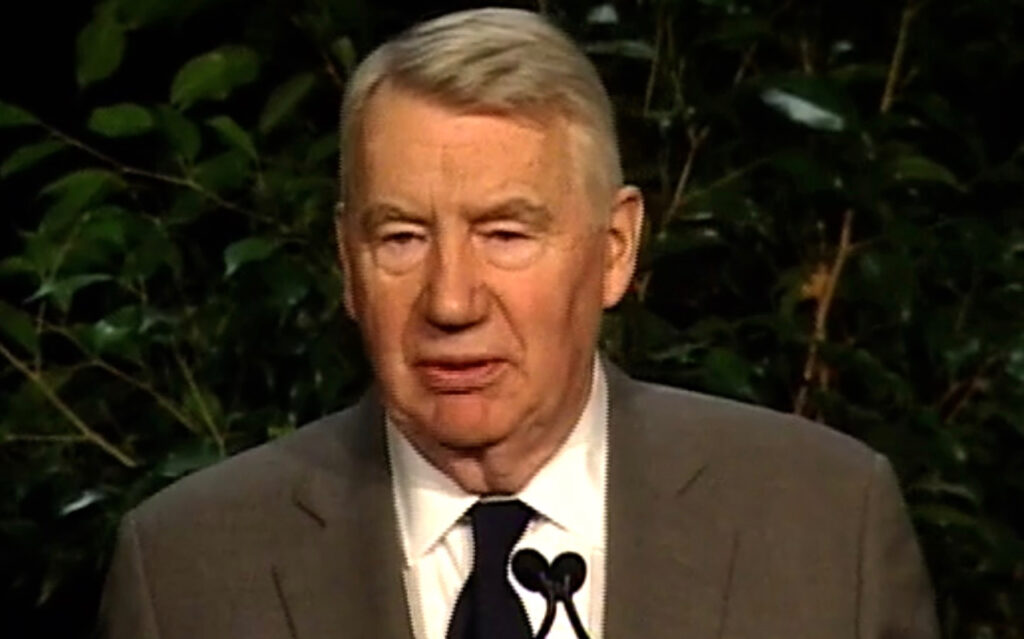

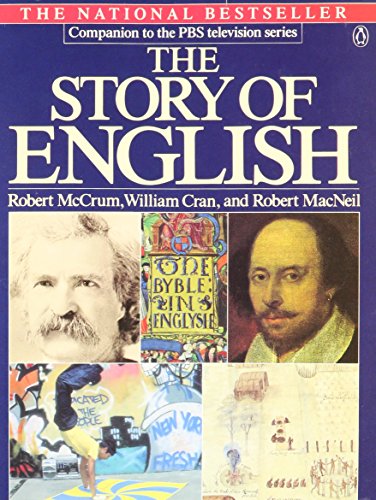

LONDON – Canadian newsman Robert MacNeill, who turns 90 today, shared my fascination with how English was used on radio and television. In 1986, the urbane and articulate co-anchor of the news programme ‘The MacNeill-Lehrer Report’ on America’s PBS-TV had spent the previous three years exploring the impact of the English language around the world. MacNeill was co-writer and narrator of ‘The Story of Engish’, a $3 million BBC co-production that remains available on DVD along with an accompanying book with the same title.

He told me he used to get angry about poor English but not any more as he had gained new respect for its strength and variety. ‘I get much less annoyed,’ he said. ‘I no longer send memos to our reporters when they use “criteria” as singular because I’ve learned from really plunging into the history of it. That is the way this language has developed over hundreds and hundreds of years. There is an instinctive welling-up of adesire to simplify the language. Foreign words by the thousands have found their way into English and whatever inflections they had in their original language – case endings or plurals or arbitrary gender – get wiped out because the English-speaking common man ultimately has no patience with that kind of complexity.’

Through every generation, MacNeill observed, there have been people who deploted what was happening to the language. ‘That is not new. Everybody who today is dismayed and fretting that the language is going to hell, that TV is ruining it, Madison Avenue is ruining it, and when they say “Winston tastes good like a cigarette should” that’s an outrage and shouldn’t be allowed because it’s corrupting our language and ruining the precision of our wonderful inheritance, they should know that people have been saying things like for centuries.’ It took him, co-writer Robert McCrum and director William Cran 26 months of reporting and filming in 16 countries. McCrum, who had the idea for the series, was an English novelist who said he took as his yardstick the words of novelist Anthony Burgess who described the language of Shakespeare and Joyce as ‘a language all thrown together that is gloriously impure’.

English has come a long way from its beginnings two-thousand years ago with a savafe tribe in northern Europe that practised human sacrifice and worshipped Mother Earth. MacNeill traces its growth through the English of Chaucerm and the various invasions especially the Norman invasion. Which he says had the effect if enriching and simplifying the language and set the stage for its great development in the Elizabethan period. ‘ The series illustrates how the English language asserted itself all over the world, in India and Africa but also in places such as the Soviet Union and Japan where the vocabulary is called ‘Russlish’ and ‘Japlish’ respectively. The international language of technology is Englsh and every commercial pilot and air traffic controller in the world uses English.

English has come a long way from its beginnings two-thousand years ago with a savafe tribe in northern Europe that practised human sacrifice and worshipped Mother Earth. MacNeill traces its growth through the English of Chaucerm and the various invasions especially the Norman invasion. Which he says had the effect if enriching and simplifying the language and set the stage for its great development in the Elizabethan period. ‘ The series illustrates how the English language asserted itself all over the world, in India and Africa but also in places such as the Soviet Union and Japan where the vocabulary is called ‘Russlish’ and ‘Japlish’ respectively. The international language of technology is Englsh and every commercial pilot and air traffic controller in the world uses English.

Episodes trace U.S. regional dialects back to their regional British origins. In one episode, Peter Hall, director of the National Theatre in the U.K., speaking at Stratford-upon-Avon , complains that modern BBC English is not adequate for Shakespeare. What the Bard intended and spoke himself, Hall says, was a language borne of England’s West Country and now heard clearly in the voices of Maryland, Virginia and Eastern Canada. Hall mimics that voice in a line from ‘Henry V’ – ‘O for a muse of fire that would ascend the brightest heaven of invention.’ ‘That,’ said MacNeill, ‘was the language of Walter Raleigh from Devon. He spoke that way and Shakespeare in one of the plays even parodies Raleigh’s way of speaking. And, of course, it was Raleigh who found the Virginia colonies.’

Later in the episode, the camera approaches Tangier Island from Chesapeake Bay to a low-lying American fishing village, crab boats by the shore, and the voice of the local preacher. MacNeill says, ‘You say, where have we heard that? Oh, yes, we just heard it from Peter Hall. What you hear is a dead-ringer for that sound of English. The people of Tangier Island and other parts of the Eastern shore speak a dialect today that, to British ears, sounds very much like the speech in Devon, Somerset and Cornwall. It is Elizabethan English very little modified.’ Other varieties of American English are traced back to their roots. Sunbelt English as it is spoken in the U.S. southeast has a direct line traceable back through Applachia and the Eastern Seaboard through to Northern Ireland and lowland Scotland in the language of Scots poet Robert Burns. ‘That episode is a very moody one, as is the chapter on Irish Engish and the effect of Irish Gaelic on the language,’ MacNeill said.

MacNeill, who is from Nova Scotia with Scottish ancestry, partnered Jim Lehrer (see photo left) from 1975 to 1995. Before that, he worked for many years in the U.K. and then moved to the United States. At the start of the ‘The Story of English’, he explains that his own manner of speech is a result of those influences. Still, it is clearly a voice from the States or Canada and that the BBC pause when it came to who should narrate the series for British viewers. In the end, they agreed and MacNeill said, ‘It is appropriate to the thrust of the series that English no longer the British language.’ In one episode, Englishman Robert Birchfield, then editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, makes the outlandish (to the British) assertion that it is American English that was now driving the language. He says that if America were suddenly obliterated then the English language would fade.

MacNeill, who is from Nova Scotia with Scottish ancestry, partnered Jim Lehrer (see photo left) from 1975 to 1995. Before that, he worked for many years in the U.K. and then moved to the United States. At the start of the ‘The Story of English’, he explains that his own manner of speech is a result of those influences. Still, it is clearly a voice from the States or Canada and that the BBC pause when it came to who should narrate the series for British viewers. In the end, they agreed and MacNeill said, ‘It is appropriate to the thrust of the series that English no longer the British language.’ In one episode, Englishman Robert Birchfield, then editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, makes the outlandish (to the British) assertion that it is American English that was now driving the language. He says that if America were suddenly obliterated then the English language would fade.

One chapter explores that in detail: the language of Shakespeare, the King James Bible and the spread of English to America. ‘We look at why the accents in the southern colonies were different from the original accents in the north,’ MacNeill said, ‘where they came from in England and how they spread out from there and were modified.’ Another chapter looks at American Black English. ‘That’s a news story in this country and a controversial one,’ MacNeill said. ‘We call the episode “Black on White” and trace the development of Black English from the earliest days of the slave trade through plantation Creole to the present-day forms. We see how Black English affected the southern accents and White English in this country. It’s a fascinating story in itself.’ While MacNeill said he believed that varieties of Engish only enrich the language, he did not say that anything goes: ‘Black English is one of the areas where pleas have been made for a special kind of tolerance, that it should be an accepted standard ad kids should be allowed to write it and use it,’ he said. ‘But at the end of the “Black on White” episode, a Black school director from Philadelphia stresses that it is imperative that we teach standard grammatical English because Black kids are going to need it to get on in anything in the world.’

Any discussion of the language raises the issue of profanity, which MacNeill said was accepted more widely but was hardly new: ‘Some of the oldest humour in English is extremely bawdy, in Chaucer for example. I think we’ve all become less prudish about it. The story of London’s Cockney showing up in Australia is bawdy in places and rollickingly funny as Cockney and Australians tend to be.’ Early in the series, the fourth word of the term ‘SNAFU’ is bleeped more out of a sense of fun, MacNeill said, ‘In some later episodes, particularly the Cockney/Australian one, there is what many people would regard as quite a lot of profanity. Some of the Austalian colloquialisms are particularly ripe. One phrase is “as unpopular as a fart in a phone box”. Things like that, common everyday expressions in Australia, are left in.’ Such richness was widespread in America too, he noted. He did not accept the notion that television was causing regional accents to fade: ‘It isn’ happening. It’s not true in Britain and it’s not true here. Contrary to conventional wisdom, television is not ironing out regional dialects.’ He had a firm belief in the ruggedness of English and he said he did not share the fears of those concerned about the incursion of Spanish into the United States.

‘Some think that you weaken your sense of nationhood if you permit rival languages to compete,’ he said. ‘They point to Canada and Belgium and they fear that if Spanish made enormous inroads then it would somehow dilute or attenuate the national identity of this country. I think that is so inconceivable that I do not worry about it.’ He pointed out that in the urgency of America’s founding fathers trying to break from Britain, there was a movement to make German the official language of the United States since German-speakers were then in the majority. There also was a movement to make Hebrew the official language. English prevailed as it did in Britain even though for 250 years after the Norman invasion in 1066, the official language was Norman French. ‘English remained the language of the common man and It has always been drivern by the comman man’s energy and impatience with complexity,’ MacNeill said. ‘I know there are lots of people in this country who would have liked the series to bash people over the head for misusing the language but I think it’s just part of a long historical trend. I think the language is in good hands.’