By Ray Bennett

LONDON – Rory Calhoun was a colourful old-time film star whose real-life story was as action-packed as any movie. Born 100 years ago today, he stole cars, spent time in prison and worked as a logger, miner, cowboy, forest-fire fighter and, briefly, as a professional boxer before he turned to acting.

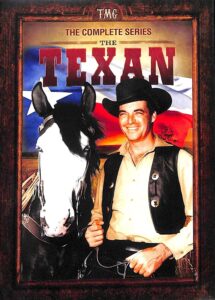

Tall, rangy and leathery, his shock of hair was silver when I interviewed him in 1982. He had been one of the handsomest cowboy stars in movies in the Fifties and Sixties when westerns could still turn a buck. He had the longest ever screen fight, with Jeff Chandler, in ‘The Spoliers’, starred with Robert Mitchum and Marilyn Monroe in ‘River of No Return’ (above) and made a lot of pictures with titles like ‘Massacre River’, ‘Four Guns to the Border’ and ‘A Bullet is Waiting’. When westerns retreated to television, he spent three years on ‘The Texan’.

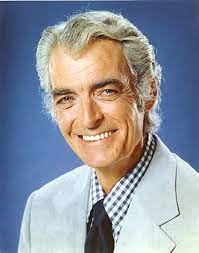

At 61, Calhoun still looked as if he would sit tall in the saddle even after a bout with pancreatitis. He was content to be wise and grandfatherly as lawyer Judson Tyler, patriarch of the McCandless clan on a CBS daytime soap opera called ‘Capitol’ (left). He was one of the old pros – along with Carolyn Jones, Constance Towers, Richard Egan and Ed Nelson signed to balance the new young blood.

At 61, Calhoun still looked as if he would sit tall in the saddle even after a bout with pancreatitis. He was content to be wise and grandfatherly as lawyer Judson Tyler, patriarch of the McCandless clan on a CBS daytime soap opera called ‘Capitol’ (left). He was one of the old pros – along with Carolyn Jones, Constance Towers, Richard Egan and Ed Nelson signed to balance the new young blood.

Calhoun averaged two episodes a week. ‘There’s no real money involved on daytime soaps,’ he said, ‘but it does get you back current and into people’s homes. I was amazed by the numbers. A lot of soap viewers associate with me because we’re the same vintage.’ He saw it as just another gig. ‘Fortunately, I’ve never been what they call a superstar so whenever I fell, I didn’t have too far to fall,’ he said. ‘I’ve always been comfortable just under the top. I’ve enjoyed all of it, even the low times didn’t bother me that much. I shrug it off, forget it and go on. Maybe there’s another rainbow over here, we’ll get that one; it’s closer and smaller, you don’t have to worry about that big one. That’s the way I’ve done it.’

Calhoun said a career in showbusiness had not been his goal as a young man. Born Francis Timothy McCown in Los Angeles, he was raised near Santa Cruz up the California coast where as a teenager he fell in with a bad crowd. He barely knew his father, a professional gambler, he told me, and he turned to stealing cars for a living. He became an expert at hot-wiring automobiles and, at 18, he had a thriving if highly illegal operation.

Fleeing across state lines in a stolen car following a series of jewelry-store robberies, he spent three years and three months in federal reformatories. That included one year in solitary confinement for allegedly inciting a riot. A prison chaplain took him under his wing and he was given a second chance.

After a chance meeting with Alan Ladd, the movie star’s wife, talent agent Sue Carroll, sent his photo to ‘Gone With the Wind’ producer David O. Selznick who signed him to a contract. Calhoun said his experience on the wrong side of the tracks proved invaluable in the movie business.

After a chance meeting with Alan Ladd, the movie star’s wife, talent agent Sue Carroll, sent his photo to ‘Gone With the Wind’ producer David O. Selznick who signed him to a contract. Calhoun said his experience on the wrong side of the tracks proved invaluable in the movie business.

‘As a juvenile delinquent, everything was a sham, everything was pretence,’ he said. ‘That’s where I learned to act – in front of creditors and the judge. I never got paid for it so this time, with a little help from training and experience, it got a little better.’

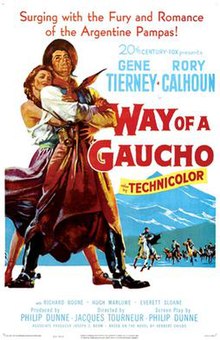

Soon, he was co-starring with Susan Hayward in ‘With a Song in My Heart’, Gene Tierney in ‘Way of the Gaucho’ and Marilyn Monroe, Betty Grable and Lauren Bacall in ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ (below). In 1954, he made ‘River of No Return’ in Jasper, Alberta. ‘That was my third picture with Marilyn,’ Calhoun said. She had an uncredited role in the western ‘A Ticket to Tomahawk’ starring Dan Daniel and Anne Baxter. ‘I knew her before she really got started,’ he said. ‘She went with a friend of mine from Texas. We always had a nice relationship. I wasn’t much older than her but she always came to me with her problems. She was in a good state of mind then. I’ve heard all kinds of reports on what happened to her and I really don’t believe any of them. I don’t know what the hell to believe.’

On ‘River of No Return’, Calhoun began a lifelong friendship with Robert Mitchum. Like Mitchum, he was the kind of movie star who was a natural target for men who wanted to prove themselves in a barroom brawl. ‘When I was younger, I was challenged a lot,’ he told me. ‘Mainly, I guess, by guys who wanted to prove to their girlfriend or wives that, hell, they could take this bum. You try to talk your way out of it, buy ‘em a drink or something, and if that didn’t work then you did the best you could’.

Of Mitchum, he said, ‘Now, there’s a guy who doesn’t give anybody any trouble. It just comes to him like a bee to a honeypot. When he was younger, he could take care of himself very well. A lot of guys made a mistake by jumping on Brother Bob. That Swede would take ‘em apart. A good friend of mine is Jack Palance. I don’t think many guys pick on Jack and it’s lucky for them even though he’s older now because Jack is a very strong guy. Like Richard Egan. He’s a powerful, powerful man. What the hell. Some guys can do it, some guys can’t and some guys said, okay, you wanna go? Let’s go. I don’t look for trouble, too old now anyhow. That was when I was young and it was fun. Now it just hurts.’

Calhoun had more than his fair share of encounters with women over the years. He was married for 21 years to actress Lita Baron (left) and when they divorced in 1969, her suit cited seventy-nine ‘Jane Does’ as co-respondents. ‘The judge asked if that was in any way injurious to my career,’ the actor said. ‘The thing was getting grim so I tried to get some humour into it. I said, oh, yes sir, it was. He asked me to tell the court exactly how. I said it hurt me because that was just the summer count; they didn’t give me the whole year. The judge started to laugh, called a recess and said he wanted to see me in his chambers. I went back there and I said, tell you what, you give me what I’m asking for and I’ll give you my little black book. He said that was bribery and he’d put me in jail. I told him I was kidding. There were no seventy-nine Jane Does. I’m sorry there wasn’t, actually.’

Calhoun had more than his fair share of encounters with women over the years. He was married for 21 years to actress Lita Baron (left) and when they divorced in 1969, her suit cited seventy-nine ‘Jane Does’ as co-respondents. ‘The judge asked if that was in any way injurious to my career,’ the actor said. ‘The thing was getting grim so I tried to get some humour into it. I said, oh, yes sir, it was. He asked me to tell the court exactly how. I said it hurt me because that was just the summer count; they didn’t give me the whole year. The judge started to laugh, called a recess and said he wanted to see me in his chambers. I went back there and I said, tell you what, you give me what I’m asking for and I’ll give you my little black book. He said that was bribery and he’d put me in jail. I told him I was kidding. There were no seventy-nine Jane Does. I’m sorry there wasn’t, actually.’

There were some high old times, though, not least with Robert Mitchum making ‘River of No Return’ in the Canadian Rockies. ‘Jasper wasn’t very big then,’ he said. ‘They had a Hudson’s Bay Store, a railroad ran through and there was a country club that would not admit actors. There also was a whorehouse where we threw a 13th birthday party for little Tommy Rettig, who was on the picture [left with Mitchum and Monroe]. Mitchum arranged it. He said he was gonna give the kid a good birthday. I didn’t know it was a whorehouse until I had to go to the can. There was this orange bathroom trimmed in purple, a wild combination. I said, wha-a-a-t? Whoops, tilt. Mitchum did it to us again.’

There were some high old times, though, not least with Robert Mitchum making ‘River of No Return’ in the Canadian Rockies. ‘Jasper wasn’t very big then,’ he said. ‘They had a Hudson’s Bay Store, a railroad ran through and there was a country club that would not admit actors. There also was a whorehouse where we threw a 13th birthday party for little Tommy Rettig, who was on the picture [left with Mitchum and Monroe]. Mitchum arranged it. He said he was gonna give the kid a good birthday. I didn’t know it was a whorehouse until I had to go to the can. There was this orange bathroom trimmed in purple, a wild combination. I said, wha-a-a-t? Whoops, tilt. Mitchum did it to us again.’

Calhoun said his most lucrative moviemaking period was from around 1957 to 1967 under contract to Fox and then Universal. Then, the old scandal magazine Hollywood Confidential dredged up his years as a juvenile car thief. Calhoun confronted it head on. ‘They found out about it and called me,’ he said. ‘They asked if I wanted to talk about it. I said, hell yes. It turned out to be an upbeat story, not an expose so much as a success story.’

Fans supported him he said, because they rooted for the underdog. There was no industry backlash. ‘Hell, no,’ said Calhoun. ‘That’s when the exploitation started. Get him a picture, let’s cash in on this.’ In 1957, he moved into television with ‘The Texan’, which he also wrote, produced and directed. ‘I wore all the hats but not all the time. You can’t,’ he said. ‘One of ‘em’s gotta come up short. I did it for three years and then I quit. I said that’s it. It was like a one-man show. I was in everything all the time. I didn’t have a sidekick or somebody to take part of the work load. I could see that one-man shows like “Have Gun, Will Travel”, “Black Saddle” and.”Lawman” were fading. CBS said no, they wanted to keep it the way it was. I told them I couldn’t hack it anymore. Rather than get run down and maybe sick, I said the hell with it.’

Fans supported him he said, because they rooted for the underdog. There was no industry backlash. ‘Hell, no,’ said Calhoun. ‘That’s when the exploitation started. Get him a picture, let’s cash in on this.’ In 1957, he moved into television with ‘The Texan’, which he also wrote, produced and directed. ‘I wore all the hats but not all the time. You can’t,’ he said. ‘One of ‘em’s gotta come up short. I did it for three years and then I quit. I said that’s it. It was like a one-man show. I was in everything all the time. I didn’t have a sidekick or somebody to take part of the work load. I could see that one-man shows like “Have Gun, Will Travel”, “Black Saddle” and.”Lawman” were fading. CBS said no, they wanted to keep it the way it was. I told them I couldn’t hack it anymore. Rather than get run down and maybe sick, I said the hell with it.’

Like many a western star, Calhoun started getting calls from European filmmakers. ‘I’d been around long enough to get a little moss on my horns and I got offers from many countries,’ he said. ‘Some of them were hysterical because they didn’t want to pay you. It was a game to me. I didn’t get mad, I just played the game.’

One producer asked him to finish a picture on his honour. ‘I said, your honour? Tell you what, you be here tomorrow with a day’s salary in cash and a limousine, I will go to work and we’ll do that every day until the picture’s finished, how’s that?’

On a Sergio Leone epic titled ‘Collosus of Rhodes’ costarring Lea Massari (above), shooting in northern Spain, he had a three-month contract. ‘Half-way through the shoot, the way they were going it was going to take four months,’ Calhoun told me. ‘At the end of my contract, we had a meeting and one of the producers said “Ay Dios”, which I learned later means “Oh, God”. I thought it he said “Adios”. I stood up, got a car to the airport and flew to London. They had to come and find me at the Savoy Hotel with a suitcase full of money, which I put in the bank. After that, they kept saying they would shoot the end of the picture that day. I said, oh no, we’ll shoot the end of the picture at the end. There’s ways to skin the cat.’

Money was never Calhoun’s big interest in life. He lived quietly in Studio City with his second wife, Sue Rhodes. ‘I’m a guy that, you give me too much pressure, it’s not worth the bucks,’ he said. ‘I’ll turn my back on it every time. That’s the way I live. The hell with it. There’s more to life. The biggest money I ever made for a picture was $150,000 in the early Sixties. I made three films that year for the same fee. You lost a lot of that in taxes, agents and things, but still it wasn’t bad. I wish I had $100,000 a a year, every year, right now. That’d be just lovely. I’d go up there in Canada to one those lakes you fly into, catch me some of those big trout and live it up. Oh, boy.’

Rory Calhoun died aged 76 on April 28, 1999.