LONDON – When Cary Grant, born this day 120 years ago, died in 1986, Time magazine film critic Richard Schickel wrote, ‘Some distant day, audiences may come to agree that he was not merely the greatest movie star of his generation but the medium’s sublest and slyest actor.’

That was clouded with rehashes of the private torments of Archibald Leach, the deprived working-class kid from Bristol, England, who grew up to be Cary grant. His marriages and affairs; his alleged tightness with a dollar; his experiments with LSD and the long-rumoured suggestion of homosexuality were paraded in books, tabloids and talk-shows.

Finally, in the middle of the night, Tony Curtis had the perfect response. When Bob Costas, on NBC’s ‘Later’, asked him what he thought of the allegations, Grant’s costar in ‘Operation Petticoat’ replied cheerfully, ‘Who Cares?’

Sean Connery called Grant ‘probably the most underrated actor to appear onscreen.’ Alexis Smith, who starred opposite him in ‘Night and Day’, said, ‘There’s a term, “romance with the camera” and I doubt anybody had a romance with the camera as Cary did.’ And Charlton Heston declared, ‘What Cary did, he did better than anyone ever has or perhaps ever will. He was surely as unique as any film star and as important as anyone since Charlie Chaplin. The only comfort we can take is we still have him on film.’

Although he was awarded a special Academy Award in 1969 and was nominated twice as best actor (for ‘Penny Serenade’ and ‘None But the Lonely Heart’), Grant never won an Oscar. Some said it was because he was viewed as a movie personality not an actor. Rosaline Russell, his co-star in the newspaper comedy ‘His Girl Friday’ (1940), disagreed. ‘Grant was different,’ Russell said. ‘He wasn’t just a personality. He could immediately go off into a spin and become any character that was called for.’

Grant always claimed to be baffled by his screen image. ‘I don’t know that I’ve any style at all,’ he said. But he acknowledged where the elements came from. He said he patterned himself on a combination of Jack Buchanan, a debonair English musical-comedy star of the Twenties and Thirties; Noel Coward and Rex Harrison. ‘I pretended to be somebody I wanted to be and I finaly became that person. Or, he became me.’

Grant always claimed to be baffled by his screen image. ‘I don’t know that I’ve any style at all,’ he said. But he acknowledged where the elements came from. He said he patterned himself on a combination of Jack Buchanan, a debonair English musical-comedy star of the Twenties and Thirties; Noel Coward and Rex Harrison. ‘I pretended to be somebody I wanted to be and I finaly became that person. Or, he became me.’

His need to become someone else certainly had its roots in his unhappy childhood. His emotionally distant mother ‘disappeared’ when he was 10. Only later did he discover that she had been placed in a nearby institution. Bewildered and hurt, the boy fended largely for himself as his father took a common-law wife and started a new family.

By the age of 14, Archie was touring England with a troupe of slapstick stage comedians, the Penders. Two years larer, they took him to New York. In 1922, when the Penders went home, Archie remained on Coney Island walking on stilts for $5 a day advertising the amusement centre. He played in revues and regional straw-hat theatre and five years later he won a small part in a Broadway Musical, ‘Golden Dawn’. Five years later, he arrived in Hollywood.

Contrary to myth, he was not discovered by Mae West. Taking the name Cary from a character he played in a stage production titled ‘Nikki’ and Grant from the Los Angeles phone book, he made his film debut as a featured player in a romantic comedy, ‘This is the Night’ in 1932.

Grant was so dismayed when he first saw himself onscreen that he went home to pack. Friends dissuaded him but four films later he remained unimpressed. In ‘Blonde Venus’, he starred opposite Marlene Dietrich as the suave sugar-daddy she turns to in order to keep her child. Directed stylishly by Josef von Sternberg, the episodic saga is interesting today mainly to watch Grant’s developing screen presence. He said it was his first good role but confessed that Von Sternberg ‘bemoaned, berated and beseeched me to relax but it was years before I could move with ease in front of a camera, years before I coud stop my right eyebrow lifting, a sure sign of inner defences and tensions’.

Mae West, who was preparing a film of her bawdy Broadway hit ‘Diamond Lil’, saw Grant on the Paramount lot dressed in uniform for his seventh film. ‘Who was that?’ She asked. ‘Oh, that’s Cary Grant. He’s making “Madame Butterfly”’ the studio chief replied. ‘I don’t care if he’s making “Little Nell”, if he can talk, I’ll take him,’ said West.

Mae West, who was preparing a film of her bawdy Broadway hit ‘Diamond Lil’, saw Grant on the Paramount lot dressed in uniform for his seventh film. ‘Who was that?’ She asked. ‘Oh, that’s Cary Grant. He’s making “Madame Butterfly”’ the studio chief replied. ‘I don’t care if he’s making “Little Nell”, if he can talk, I’ll take him,’ said West.

She took him, told him onscreen to come up and see her sometime and the short and saucy ‘She Done Him Wrong’ was one of the biggest box-office smashes of 1933. Grant said sometime later, ‘She knows so much. Her instinct is so true, her timing so perfect. It’s the tempo of the acting that counts rather than the sincerity of the characterisation.’

It was a lesson he studied further in their second big hit, ‘I’m No Angel’ and by the time he teamed with Katharine Hepburn as a carnival con-man in ‘Sylvia Scarlett, director George Cukor coulld see the difference.

‘Cary knew the kind of life we showed in the picture. He had started his career walking on stilts,’ Cukor said. ‘He’d had enough experience by this time to know what he was up to. Suddenly the part hit him and he felt the ground under his feer.’

Grant made several more films and in 1937, he had two hit comedies – ‘Topper’, playing a ghost, and ‘The Awful Truth’ as a reluctant divorcee. Director Howard Hawks declared, ‘Cary Grant became a star when he became confident in himself. He’s doing things now, little gestures, facial expressions, that he wouldn’t have dared do when he first came to Hollywood because he lacked confidence. Now, he’s got it.’

Of course, Hawks had just signed Grant to star in ‘Bringing Up Baby’ but he was right. The classic screwball comedy pits Grant, as a paleontologist in search of a rare dinosaur bone and a million dollars for his museum, with heiress Katharine Helpburn, who has an aunt with the money and a pet leopard named Baby.

Oddly, the streamlined farce, which is regarded as a classic today, was a flop in 1938. So was their follow-up, ‘Holiday’. Fortunately for Grant, who was not yet regarded as a mahor star, Hepburn got the blame. Theatre operators labeled her ‘box-office poison’. Grant went on to the epic comedy adventure ‘Gunga Din’ and gave RKO Pictures the biggest success in the syudio’s history.

‘His Girl Friday’ (1940) with its rapid-fire dialogue, cemented the actor’s stardom. When Hepburn wanted to film her Broadway hit, ‘The Philadelphia Story, Warner Bros. tried to buy it for Bette Davis but MGM came to the rescue provided Hepburn chose two major leading men, preferably those under contract to MGM. Hepburn approved James Stewart as the sometimes inebriated reporter but she balked at Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy and Robert Taylor as her ex-husband.

Howard Hughes, who helped finance the stage production, suggested his friend Cary Grant who took the part so long as he had as much screen time as Stewart, received top billing and $100,000 fee was paid to the British War Relief Fund. Producer Joseph L. Mankiewicz revealed later that Grant had not signed on then MGM would never have made the picture. As it was, Hekpburn returned to Hollywood’s good graces oscar?, Stewart won an Oscar, Grant had another hit and movie fans have a comedy to treasure.

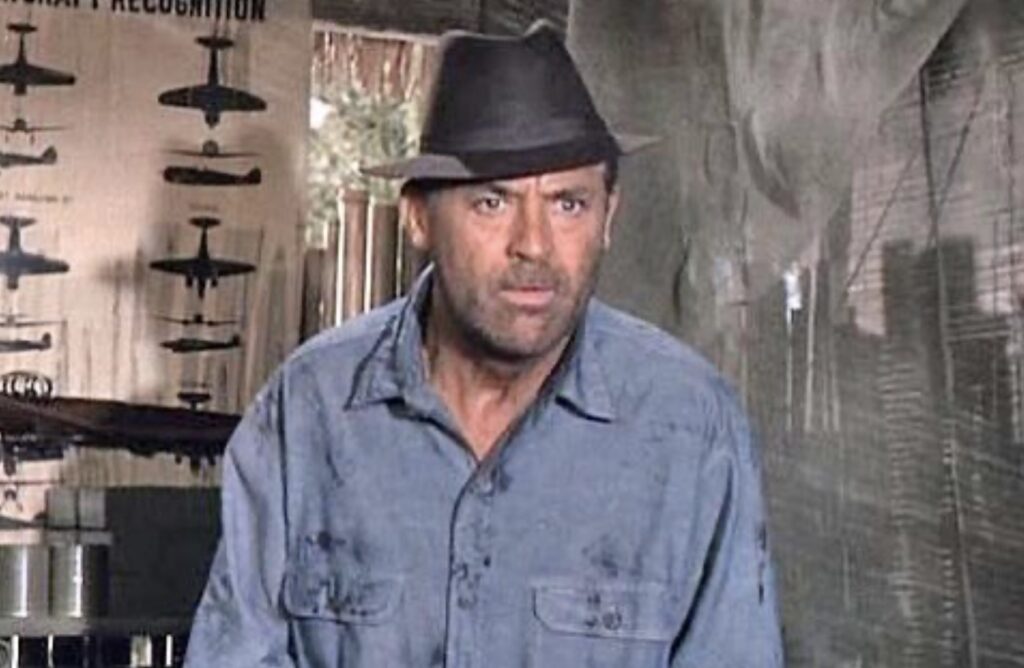

Throughout the Forties – ‘Notorious’, ‘Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House’, ‘I Was a Male War Bride’; the Fifties – ‘’To Catch a Thief’, ‘An Affair to Remember’, ‘Indiscreet’, ‘North by Northwest’; and the Sixties – ‘That Touch of Mink’, ‘Charade’ (with Audrey Hepburn pictured above) Father Goose’ – Grant reigned supreme. After ‘Walk Don’t Run’ in 1966, he retired.

Turning his attention to his lomg-awaited only child, Jennifer, from his fourth marriage, to Dyan Cannon, he never acted again. Over the year he turned down many films that might have shown us a different Cary Grant – ‘Roman Holiday’, ‘Can-Can’, ‘Around the World in 80 Days’, ‘Lolita’, ‘The Music Man’, ‘Sleuth’ and ‘Heaven Can Wait’.

He said the role that revealed his own character best was the unkempt old grouch he played in ‘Father Goose’ in 1964 (pictured above) . ‘I’m closer to him than to any man I’ve ever played,’ he said. ‘As precise as I’ve always been about my attire and appearance, there has been that hidden desire, a subconscious urge, to go around like that unshaven and untidy. I’m not a lover really and I don’t drink but I am sometimes grumpy and have that hard shell of defence, which can be softened at the right time with the right person.

He refused, however, to reveal too much. Perhaps the greatest loss is that he turned down the role that went to James Mason in ‘A Star is Born’. Director George Cukor said he got him to read the script: ‘Cary read his part aloud with me. He was absolutely magnificent, dramatic and vulnerabble beyond anything I’d ever seen him do. But when he finished, I was filled with a great sadness and I knew that Cary would not do the role. He would never expose himself like that in public.’

Who can blame him? As he once said, ‘Every man wants to be Cary Grant. I want to be Cary Grant.’ The mystery that was Archibald Leach was long gone but in his films he will be Cary Grant forever.

This story appeared first in Orbit Video magazine in August 1989