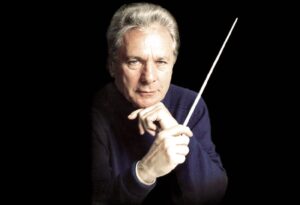

French film composer Maurice Jarre, who was born 100 years ago yesterday, is invariably linked with director David Lean but there were other filmmakers he worked with more than once and he had interesting anecdotes about them.

French film composer Maurice Jarre, who was born 100 years ago yesterday, is invariably linked with director David Lean but there were other filmmakers he worked with more than once and he had interesting anecdotes about them.

Australian director Peter Weir invited Jarre to Australia in 1982 to score ‘The Year of Living Dangerously’ starring Mel Gibson and Sigourney Weaver (pictured below). The Frenchman was impressed when a giant limousine awaited him in Sydney and when Weir told him how much he admired his work as director of the Theatre National Populaire based near Lyon in France.

More important was that Weir said he could do whatever he wished with the music. ‘I wanted to write something totally electronically but in the U.S. producers insisted on a full orchestra,’ Jarre told me when I interviewed him at the World Soundtrack Awards in Gent in 2003. ‘I discovered there was no one in Sydney with synthesiser experience sophisticated enough so I decided to do it myself with an engineer. It was a very long process as I had to get a sample of each instrument. It took me about three months working from nine in the mornng to 2 a.m. Peter gave me freedom and in the end he was very happy.’

Two years later came Weir’s ‘Witness’, starring Harrison Ford, with its much-admired barn-building scene (pictured). ‘The music for that scene was one of Peter’s favourites,’ Jarre told me, ‘although at first he told me not to spend any time on it as he already had music in place. I studied very thoroughly to know how he edited the film; analysed it very carefully. I thought music for the scene should start slowly – a bass line, a counterpoint and then, like the barn, the music starts to build. As I was almost finished, I heard Peter outside the studio sayiing, “What’s that? What is that?” He came in and I explained and he said, “Oh, that’s fantastic!” He said it was a piece I could play in concert. I transcribed it for an orchestra and we recorded it in Los Angeles. It was very well received.’ It won the BAFTA for best score and earned an Oscar nomination.

Two years later came Weir’s ‘Witness’, starring Harrison Ford, with its much-admired barn-building scene (pictured). ‘The music for that scene was one of Peter’s favourites,’ Jarre told me, ‘although at first he told me not to spend any time on it as he already had music in place. I studied very thoroughly to know how he edited the film; analysed it very carefully. I thought music for the scene should start slowly – a bass line, a counterpoint and then, like the barn, the music starts to build. As I was almost finished, I heard Peter outside the studio sayiing, “What’s that? What is that?” He came in and I explained and he said, “Oh, that’s fantastic!” He said it was a piece I could play in concert. I transcribed it for an orchestra and we recorded it in Los Angeles. It was very well received.’ It won the BAFTA for best score and earned an Oscar nomination.

Jarre’s experience on Weir’s next picture ‘The Mosquito Coast’ in 1986 was not so pleasant. The director gave him the script before he started to shoot in Belize and asked him to write music for seven or eight sequences so he could play them for the actors. Jarre obliged and when the shoot began, Weir told him, ‘I am so happy. The actors are working with the music.’

Then Weir put together a rough cut and they tried to put the music to the film. ‘It didn’t work at all,’ said Jarre. ‘He said he didn’t understand why it didn’t work but it meant I had to write new music completely. That was an interesting experience.’

Jarre said he threw the original music away. ‘I thought it was a beautiful film although critics thought Ford was miscast. I worked with a synth player but in the end the musical concept from the script was wrong.’

The Frenchman said it taught him something: ‘Many of my colleagues say they like to write from a script but for me it didn’t work. For me, the inspiration is when you see the film even if it’s a rough cut. When I saw the first cut of “Lawrence of Arabia” (top picture) … I saw 40 hours of film. The beauty of the locations, the actors … neither Peter O’Toole nor Omar Sharif were known then but they were fantastic. The first lttle theme I wrote became the theme of Lawrence. I had a home on Half Moon Street in London. Producer Sam Spiegel asked me to come to London for one month. I did not know much about Lawrence so I read about his life and his time. It was a very interesting experience. I realised that the inspiration definitely comes when you see the film.’

Jarre later provided scores for Weir’s ‘Dead Poets Society[ and ‘Fearless’ and he worked twice with British filmmaker Adrian Lyne, on ‘Fatal Attraction’, starring Michael Douglas, Glenn Close (pictured below) and Anne Archer, and ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ with Tim Robbins. The first really put him to the test. ‘This crazy film, “Fatal Attraction”, did not have too much music,’ Jarre said, ‘and Adrian told me he did not want scary music. He wanted something discreet and he was happy.’

One week before the release of the film, the studio held a preview. Jarre told me, ‘The notes were very good but the studio said something was wrong with the ending. It was crazy, the writer would rewrite the last seven or eight minutes of the fim. They said the actors wanted to do it but they really did not. The studio said either they did it or they would put the film on the shelf. Adrian showed me new scenes and said he neeed eight or 10 minutes of new music. That was Friday and we would record on Monday morning. I spent two days and nights writing. We recorded the music on Monday and by Monday night it was ready for release. The studio people were very happy. They said, “You saved the film.”’

Jarre, who died in 2009, is inextricably linked with David Lean as his three Academy Award wins from nine nominations were for scores to the British director’s pictures starting with ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ in 1962 and followed by ‘Dr. Zhivago’ and ‘A Passage to India’. He worked with a great many other top directors including Alfred Hitchcock, Fred Zinnemannm, William Wyler, Rene Clement, Richard Brooks, John Frankenheimer and John Huston.

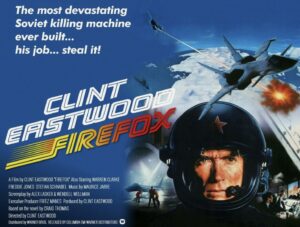

He also worked with Clint Eastwood and, given that filmmaker’s preference for his own music, I was curious about his experience working on the 1982 action picture ‘Firefox’.

He also worked with Clint Eastwood and, given that filmmaker’s preference for his own music, I was curious about his experience working on the 1982 action picture ‘Firefox’.

‘Clint Eastwood is an interesting man, very nice, very charming but he does not understand too much about music in film,’ Jarre said. ‘He’s a fan of jazz … on his latest picture, he does his own music. It sounds like putting him down but it’s not that. He likes sound effects but not music. It was not one of his best pictures, not a good film, I liked the man, absolutely adorable, no temper. I enjoyed very much working with him but the film was not interesting from the music point of view.’