Joshua Marston’s “The Forgiveness of Blood” offers the Hatfields and the McCoys Albanian style taken seriously with a good deal of suspense. It screens tonight and Sunday at the Toronto International Film Festival, and at the BFI London Film Festival on Oct. 13.

By Ray Bennett

California-born filmmaker Joshua Marston, whose award-winning 2004 picture “Maria Full of Grace” dealt with Columbian drug dealing, turns his attention to the conflict between ancient traditions and modern life in Albania in “The Forgiveness of Blood.”

It’s a familiar tale of territorial rights and family honor but it is told well and the film features appealingly natural performances by non-professionals. It could reach beyond festivals in certain territories, particularly those that have populations with a Balkan heritage.

In the rural north of the formerly communist nation, bread is still delivered by horse and cart but every teenager has a mobile phone. The police have modern vehicles and weapons but elders dish out justice according to the 15th century Balkan code known as the Kanun.

A conflict over the right of way on one family’s land leads to anger and violence, and when a man dies there is no way to avoid a blood feud. Marston and Albania-born screenwriter Andamion Murataj have fashioned an absorbing tale about the impact of such old-fashioned rules, especially on the younger generation.

The director has a good eye and British cinematographer Rob Hardy (“Boy A,” “Red Riding”) captures shrewdly the many contrasts of ancient and modern in tools, buildings and terrain.

Refet Abazi plays Mark, a delivery man whose daily route with horse and cart has taken him across trails used since his grandfather owned much of the land. But a temperamental man named Sokol (Veton Osmani) now owns the land and he places rocks on the ground to block Mark’s way.

When Sokol insults him and his family in the presence of his teenaged daughter Rudina (Sindi Lacej), Mark returns with his brother Zef (Luan Jaha) to set things right. The encounter occurs offscreen but soon Zokol is dead, Zev is in prison, and Mark is in hiding.

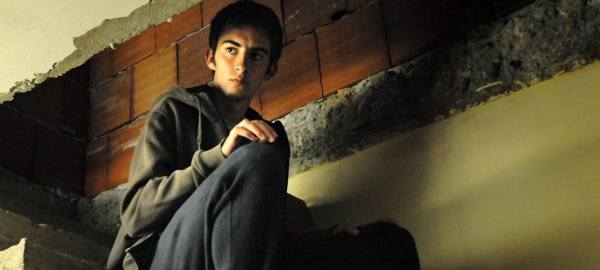

A blood feud is declared that means Mark’s teenaged son Nik (Tristan Halilaj) and his little brother cannot leave the house in fear of retribution. Nik, who has ambitions of opening an internet café once he graduates and has a school sweetheart, Bardha (Zana Hasaj), chafes under incarceration although Rudina thrives in her new duties driving the horse and cart to deliver bread and other goods.

Marston sets a level of increased tension as Sokol’s family make further threats and attempt to intimidate Rudina while Nik risks his life to sneak out at night to see his girlfriend. Loyalties become strained as the youngsters begin to challenge what they see as the stubborn futility of the old ways.

The contrasts between unspoiled countryside and urban development and the clash between rural intransigence and youthful impatience add depth to an accomplished and suspenseful drama.

Venue: Toronto International Film Festival; In Competition; Cast: Tristan Halilaj, Sindi Lacej, Refet Abazi, Zana Hasaj; Director, screenwriter: Joshua Marston; Screenwriter: Andamion Murataj; Producer: Paul Mezey; Director of photography: Rob Hardy; Production designer: Tommaso Jamieson; Music: Jacobo Lieberman, Leonardo Heiblum; Editor: Malcolm Jamieson; Costume designer: Emire Turkeshi; Production: Journeyman Pictures; Sales: Fandango Portobello; No Rating, runs 109 minutes

This review is from the Berlin Film Festival and appeared in The Hollywood Reporter