By Ray Bennett

LONDON – With his blind left eye, American character actor Jack Elam, who was born 100 years ago today, made a perfect villain in hundreds of TV shows and feature films but he told me he was a better auditor than he was an actor.

He started out in the film business as a chartered accountant and worked as an auditor for Samuel Goldwyn Studios and General Services Studios: ‘I do believe that I was as good an auditor as there was when I was an auditor. I was as high a salaried auditor as there was so I knew my business. I felt a very great self-respect as an auditor, which as an actor is pretty hard to feel because you might like what I’m doing and the other fella doesn’t like it at all. You say, jeez, I thought you were great in such-and-such and he says he thought it was a terrible fucking thing and you were awful. There are no matters of opinion in audting. If the sonofabitch balances, you can shove it up your ass, your opinion. You can go fuck it, you know?’

You might think the kind of personality that balances columns of figures wouldn’t necessarily have the imagination and the creative freedom to be an actor, but Elam said: ‘It doesn’t take any imagination or creative freedom to be an actor. Doesn’t take either one of those things. It just takes the guts to go stand in front of a camera and talk, the ability to memorise the goddam lines. There’s no creative thinking about acting to that extent. There’s no more creative thing about acting than there is about auditing. You come to me with your books to balance and I can look at ‘em and say, wait a minite, I think I know where I’ll find it, and I can save thousands of hours of work by being able to understand where the shortage is. That’s just as creative as actors creating. When I went into it, I didn’t know anything about acting. I’ve learned through doing it.’

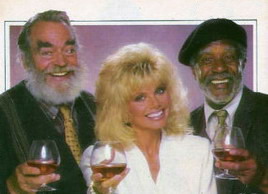

His left eye was blinded when a fellow boy scout accidentally stuck him with a pencil as a boy. He quit accounting when a doctor told him he risked sight in his other eye if he  continued staring at financial reports. He became an actor when he helped finance a friend’s movies in return for roles. I spoke to the genial but thoroughly professional actor – who died in 2003 – at an NBC-TV gathering during the Television Critics Association tour in Los Angeles in January 1987. Famous for his evil roles, he was equally adept at comedy in movies and TV shows. That year, he appeared in a sitcom titled ‘Easy Street ’as an ageing hillbilly named Bully who is brought to live in Beverly Hills by a distant and suddenly rich relative played by Loni Anderson (above with Elam and Lee Weaver).

continued staring at financial reports. He became an actor when he helped finance a friend’s movies in return for roles. I spoke to the genial but thoroughly professional actor – who died in 2003 – at an NBC-TV gathering during the Television Critics Association tour in Los Angeles in January 1987. Famous for his evil roles, he was equally adept at comedy in movies and TV shows. That year, he appeared in a sitcom titled ‘Easy Street ’as an ageing hillbilly named Bully who is brought to live in Beverly Hills by a distant and suddenly rich relative played by Loni Anderson (above with Elam and Lee Weaver).

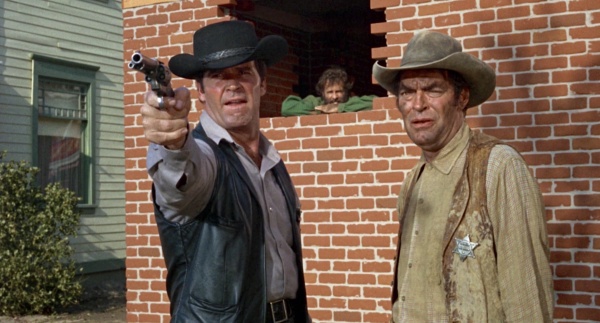

I asked if he had a favourite of the films he’d made: ‘No way to tell you. Actually, it would be a series of steps. My favourite early one would be “Rawhide” with Tyrone Power and Susan Hayward (pictured with Elam left) in 1950 because it’s the one that blasted my career and I’ve never been out of work since. Then, I’d go to “Support Your Local Sheriff” with Jim Garner (pictured below) because that was the change into comedy. There’ve been many that I loved. Listen, let me tell you something. I would have been very happy to have played that Frankenstein monster the rest of my life. I loved that sonofabitch. I like Bully in this show and it’s a nice company. I just don’t like the process. I don’t like the live camera stuff.’

I asked if he had a favourite of the films he’d made: ‘No way to tell you. Actually, it would be a series of steps. My favourite early one would be “Rawhide” with Tyrone Power and Susan Hayward (pictured with Elam left) in 1950 because it’s the one that blasted my career and I’ve never been out of work since. Then, I’d go to “Support Your Local Sheriff” with Jim Garner (pictured below) because that was the change into comedy. There’ve been many that I loved. Listen, let me tell you something. I would have been very happy to have played that Frankenstein monster the rest of my life. I loved that sonofabitch. I like Bully in this show and it’s a nice company. I just don’t like the process. I don’t like the live camera stuff.’

In an earlier press conference, he said Burt Kennedy (‘The Rounders’, ‘The War Wagon’, ‘Support Your Local Sheriff’) was the best director of westerns he’d worked with and I told him that surprised me given all the directors he’d worked with. He said, ‘I’ll tell you what surprised the shit out of me: somebody just asked me what has he done. I thought, you’re putting me on. Burt Kennedy, in my opinion, has done some of the best westerns. For example, ‘Support Your Local Sheriff’ was one of the biggest grossing westerns of the year. It won the Box Office Award, all kinds of award. I can’t believe that people don’t know what Burt Kennedy has done.’

He put Howard Hawks (‘Rio Bravo’, ‘El Dorado’, ‘Rio Lobo’) in second place: ‘I put Howard at number two because Howard’s gone and Burt is a personal friend. I did only a couple of pictures for Howard. I’ve done nine for Burt so that becomes a difference. I think he’s very definitely in Howard’s category, though, because they work the same way. Howard was very easy. We’d sit around, talk about the script, he’d ask if we had any ideas, any changes we wanted to make. He’d ask Duke what d’you think? Duke’d say, well, I think we oughta come over the hill there, we oughta have more guys than we’ve got. Howard would say, fine, Duke, we’ll do that. It was very congenial but he had his finger on everything going on.’

Did they think they were creating art? ‘No, it was just let’s do it. It was our job. It was a professional thing. Our job is to make a movie. In those days … let’s go back to Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Robert Taylor, those guys. I never saw one of ‘em ever late. Duke Wayne (with Elam in ‘Rio Lobo’ below). They were never late. I never saw one of ‘em didn’t know his lines. They came prepared, they came on time. They expected to have to work, it was a profession. The making of the picture itself, they didn’t consider themselves some special kind of artist. They considered themselves, I don’t know, actors who were just hired to fill a role.’ Were the directors were in sync with that? ‘Oh, yes, absolutely, right down the line. In those days, the directors, even the ones that were mean like John Farrow (“Ride Vaquero” 1953), he was kind of a mean man but he was right on the nose.’

Was working with Sergio Leone different? ‘Well, Leone had all the money and all the time in the world so it was almost like a game to him. I don’t know that I ever made a contact with him because I only did the one show with him and I was on it only about ten days.’ Leone directed Elam in one of the most iconic scenes in western movies – a man, a gun and a housefly. In the opening scene of Sergio Leone’s epic ‘Once Upon a Time in the West’ (below), three bored gunmen await the arrival of a train at a dusty frontier outpost. One of them, played by Elam, sits in a chair as flies buzz around his grizzled chin when suddenly he traps a fly in the barrel of his six-shooter. The special effects man had a fly on a wire and they could have done the shot in two hours, he told me: ‘Leone said no, no, he wanted it to fly. We took a day and a half before I caught a fucking fly. He smeared apricot jam from the lunch table on my beard thinking it would attract flies. Well, they came to my beard but they wouldn’t go where I could catch ‘em. Then he smeared honey in my beard. No luck. One afternoon, we broke and there was some watermelon on the set. He spread some watermelon on me. Millions of flies came and I caught a fly.’ Leone offered him another film afterwards but Elam said drily, ‘I had a good enough time on that one. I was busy so I said I’ll just pass.’

Did spaghetti westerns ruin things for the Hollywood western? Elam said, ‘I think the greatest damage was probably “Blazing Saddles”. It was a big success, a $100 million gross or whatever it was but it made fun of westerns and I don’t think you can make fun of westerns and then come back. Burt Kennedy had two or three good prokects in the works and he and I went to see “Blazing Saddles” amd neither one of us liked it. All of his projects were cancelled because none of them were comedies. Go back and look at the record, there were no westerns made since that date except the occasional one or two like ‘Pale Rider’, there would be one or two but that ended the eight or ten westerns a year, that ended it.’ I suggested that perhaps sci-fi movies also contributed as they were westerns in space: ‘I think they probably had a lot to do with it. We have a generation now … I don’t see any cowboys. I see “Star Wars” with kids … I’ve got two kids and I don’t see any cowboys at home. Westerns are too straight, maybe, there’s a black hat, there’s a white hat.’ What about Rambo? ‘I can’t relate him to a western at all. That’s something kids can understand because there’s no dreaming to that. Let me play you some cowboy music, there’s a dream to the cowboy. The cowboy’s a quiet soul. Go look at the westerns, really look at Gary Cooper and Bob Taylor and those westerns they did, and Kirk Douglas, those guys, they don’t come on in front. Rambo is a front character, it’s another personality entirely so I don’t see any relationship of any kid. Of course, I’m in love with the other thing.’