By Ray Bennett

LONDON – Ry Cooder, who turns 75 today, told me that he knew that he would be a musician when he discovered the blues as a kid. When I first heard his slide guitar, I imagined he came from from some swamp in Louisiana or Mississippi but I was wrong. The legendary guitarist, singer-songwriter and film composer Ryland Peter Cooder is a California boy from Santa Monica by the sea.

‘When I was little, you couldn’t go to Tower and buy all the records or get the books,’ he said. We spoke in 1986, long before streaming changed everything. ‘I knew some older people who would play me a Leadbelly or Woody Guthrie record,’ he recalled. ‘I didn’t know what it was except that it was different from anything else I’d ever heard. It wasn’t Santa Monica. It was from someplace else, very exotic, very strange and very compelling.’

He knew it was something he wanted to learn how to play but those around him said, ‘Well, this is the blues. These people are different from you and you can’t play this music.’ Cooder was around six or seven years old at the time. ‘I said, well, I like it. I’m gonna stick with this thing and do the best I can,’ he told me. ‘I’m just a little kid. I don’t know what the world is all about. I don’t know about poor people in the South and picking cotton and chain gangs. Then I saw photographs of the dust-bowl, beat-up cars, and I thought, my God, what is this all about? I was curious about it and I didn’t think that those people were different from me. I didn’t see myself as being a white, middle-class kid from Santa Monica. I think it would have stopped me in my tracks, if I did.’

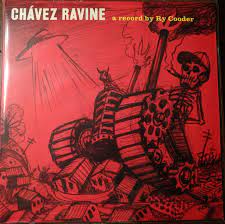

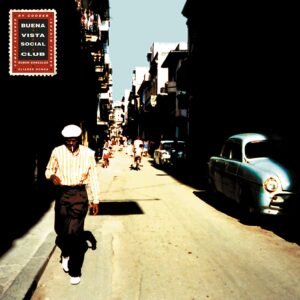

One of the most influential figures in the history of contemporary popular song and a multiple Grammy Award winner, Cooder has played with a great many artists including Captain Beefheart, Randy Newman, Van Dyke Parks and the Rolling Stones. His own eclectic jazz, blues and folk albums, the many soundtracks and such masterpieces as ‘A Meeting by the River’ with V.M. Bhatt, ‘The Buena Vista Social Club’, ‘Paradise and Lunch’, ‘Borderline’, ‘Chavez Ravine’, ’My Name is Buddy’, ‘I, Flathead’, ‘Pull Up Some Dust and Sit Down’, ‘Election Special’ and his most recent, ‘The Prodigal Sun’ in 2018 are essential in any album collection. Cooder’s scores for Wim Wenders’s ‘Paris, Texas’ and Walter Hill’s ‘The Long Riders’ and “Crossroads,” are must-have albums as well as the Warner Bros. double-album ‘Music by Ry Cooder’, which is the only place I know to hear his haunting tracks from Hill’s ‘Southern Comfort’ and ‘Streets of Fire’ and Louis Malle’s ‘Alamo Bay.’

One of the most influential figures in the history of contemporary popular song and a multiple Grammy Award winner, Cooder has played with a great many artists including Captain Beefheart, Randy Newman, Van Dyke Parks and the Rolling Stones. His own eclectic jazz, blues and folk albums, the many soundtracks and such masterpieces as ‘A Meeting by the River’ with V.M. Bhatt, ‘The Buena Vista Social Club’, ‘Paradise and Lunch’, ‘Borderline’, ‘Chavez Ravine’, ’My Name is Buddy’, ‘I, Flathead’, ‘Pull Up Some Dust and Sit Down’, ‘Election Special’ and his most recent, ‘The Prodigal Sun’ in 2018 are essential in any album collection. Cooder’s scores for Wim Wenders’s ‘Paris, Texas’ and Walter Hill’s ‘The Long Riders’ and “Crossroads,” are must-have albums as well as the Warner Bros. double-album ‘Music by Ry Cooder’, which is the only place I know to hear his haunting tracks from Hill’s ‘Southern Comfort’ and ‘Streets of Fire’ and Louis Malle’s ‘Alamo Bay.’

His entry into film music occured when, along with Randy Newman and Jack Nitzsche, he contributed to the soundtrack of the 1970 British crime drama ‘Performance’ starring Mick Jagger and James Fox directed by Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg.

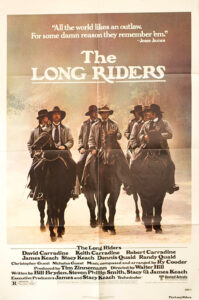

American film director Walter Hill was planning his western ‘The Long Riders’ when he heard Cooder’s 1978 album ‘Jazz’. Instead of having a traditional, big orchestral Western score for the picture, Hil wanted something organic to the 19th century but not what a musicologist might find in old material. ‘I wanted it to be reinterpreted in a way that would mean something to a contemporary audience, which is almost a complete definition of what Ry Cooder does,’ Hill told me. ‘He’s fabulous at working with traditional forms of American music and reinterpreting them in such a way that they have a current, contemporary validity.’

American film director Walter Hill was planning his western ‘The Long Riders’ when he heard Cooder’s 1978 album ‘Jazz’. Instead of having a traditional, big orchestral Western score for the picture, Hil wanted something organic to the 19th century but not what a musicologist might find in old material. ‘I wanted it to be reinterpreted in a way that would mean something to a contemporary audience, which is almost a complete definition of what Ry Cooder does,’ Hill told me. ‘He’s fabulous at working with traditional forms of American music and reinterpreting them in such a way that they have a current, contemporary validity.’

What Hill didn’t know was how Cooder felt about ‘Jazz’. ‘It turned out to be the album he hates the most,’ the director said. ‘He just shudders.’ When I spoke to Cooder, he agreed. ‘It was an honest effort but we weren’t anywhere near the level at which that music has to operate to be truly good,’ he said. ‘It’s awfully polite. I like parts of it. I don’t care for the tempos; the instrumentation is too nervous. I love that music but it’s very hard to get it right.’

Still, Hill said there were a couple of cuts on it that he thought had a sound that might be useful on his western. ‘Ry came in and we talked and got on quite well,’ Hill said. ‘He understood what I wanted to do. We thought we could work well together as basically we use the same techniques. He didn’t want full scoring sessions as you do usually with movies as that takes time and money. He used over-dubbing, which works very well because if I wasn’t happy with something, he could change it instantly and it wasn’t economically crippling. When you have the big orchestra, the composer will play something for you ahead of time but you never really quite know what it’s gonna sound like. It’s one person on the piano saying “This is where the brass comes in, this is where the percussion enters …” Working with Ry, you build as you go and you can change things and modulate. That’s very good from my point of view.’

Cooder said, ’I was pretty lucky there. Walter really helped me out. He saw a use for what I do. I always figured there was a use for it but I couldn’t quite figure it out. If not enough people have a use for what you do, then what do you do? But being a practical man, Walter saw a use for the idea. He’s not the only one but he’s the main one. Nobody was welcome from the record business side for years. A very conservative branch of the film industry, is music; much more so than cinematography or acting in terms of style. But now you have younger people in the film business who expect to hear it. It’s part of their life experience and their environment, and they can sell it.’

Cooder said, ’I was pretty lucky there. Walter really helped me out. He saw a use for what I do. I always figured there was a use for it but I couldn’t quite figure it out. If not enough people have a use for what you do, then what do you do? But being a practical man, Walter saw a use for the idea. He’s not the only one but he’s the main one. Nobody was welcome from the record business side for years. A very conservative branch of the film industry, is music; much more so than cinematography or acting in terms of style. But now you have younger people in the film business who expect to hear it. It’s part of their life experience and their environment, and they can sell it.’

Cooder and Hill’s other collaborations were on ‘Johnny Handsome’, ‘Trespass’, ‘Geronimo: An American Legend’ and ‘Last Man Standing’. He also worked with Tony Richardson on ‘The Border’, Michael Manning on ‘Blue City’, Wim Wenders on ‘The End of Violence’, Mike Nichols on ‘Primary Colors’ and Wonk Kar-wai on ‘My Blueberry Nights’.

Cooder observed that music reflects time and space: ‘If you hear old blues music that came out of the Southern states, especially Mississippi, and you go down there and catch the way the place looks and smells,’ he told me, ‘you understand where the tempos are coming from and where the space in the music comes from.’

Music he heard as a chid made him see places he’d never visited. ‘When Woody Guthrie used to say, “I’m goin’ down the road feelin’ bad”, you really saw it happening,’ he said. ‘I’d listen to those records as a kid and I could see every foot of the road. I try to bring that to my pictures.’