By Ray Bennett

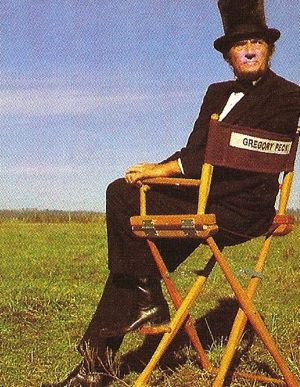

In 1982, Gregory Peck achieved a lifetime ambition to portray his idol Abraham Lincoln onscreen. It was a cameo appearance in the CBS miniseries “The Blue and the Gray”, which became the subject of a special issue in TV Guide Canada.

I traveled from Toronto to Southern California to interview director Andrew V. McLaglen and members of the cast such as Stacy Keach, John Hammond and, of course, Peck.

In our lengthy interview at Peck’s lovely home in the Holmby Hills in L.A., he spoke at length – unhesitating and in great detail with no resort to a book or notes – about Lincoln and his admiration for the man.

I asked him if TV Guide Canada could run his comments under his name, to which he agreed. He later sent me a note of thanks for giving him his first byline. With the UK release this weekend of Steven Spielberg’s wonderful “Lincoln” starring Daniel Day Lewis, Peck’s words came to mind.

He told me: “I have admired Abraham Lincoln since I was a boy. I learned the Gettysburg Address when I was 12, and recited it in school. I first read Carl Sandburg’s “Lincoln” in university, at Berkeley, and I was totally absorbed by it.”

Over the years, he had accumulated something like 200 books about Lincoln, he said: “That doesn’t make me a top-of-the-line collector of Lincolniana; I’m somewhere in the middle. But often, when I have a moment at any time of the day or night, I’ll reach for one of my Lincoln books, open it anywhere and have a visit with him. He is my ideal.”

Peck had always wanted to play him but nobody asked him, and he thought there had not been very many plays or films about him in recent years, at least not one he though amounted to anything in the 40-odd years since Raymond Massey did “Abe Lincoln in Illinois” and Henry Fonda did “Young Mr. Lincoln”.

He said: “He’s a difficult subject to dramatize because he’s a secular saint. You can’t praise him any more than he’s been praised; you can’t heap any more adulation on him. Nothing is more boring than a play that simply rediscovers that a man is good. You have to find a bone of contention, a source of conflict, and with Lincoln that’s not easy to do.”

Most people seemed to think Lincoln was rather dour and glum, and his appearance certainly gave that impression, Peck said, but the man was full of humour: “He liked nothing better than a good old story-telling session; telling jokes and yarns about his rustic days on the frontier and his experiences as a young lawyer on the Illinois circuit.”

Lincoln worked on his address for a couple of weeks before he went to Gettysburg, Peck observed: “It’s a myth that he scribbled it on the back of an envelope on the train. He had worked on it several times at the White House, knowing he had that engagement. In fact, he went to Gettysburg that day, Nov. 19, 1863, with a purpose in mind: not merely to dedicate the cemetery where men from the terrible battle of the previous July were buried, but to restate for the North and for the South what the war was all about.”

The issue was not slavery, Peck said, although morally Lincoln was against it: “He often said that if he could preserve the Union all-free, he’d preserve it; if he could preserve it all-slave, he’d preserve it; if he could preserve it half-free and half-slave, he’d preserve it. Preserving the Union was the primary objective of his administration, and of his life.”

Peck described the Civil War as the most critical event in U.S. history, and the most tragic: “The casualties of 618,000 equalled the number of casualties in all of our other wars including the Revolutionary War, up to the time of Vietnam. It was a horrific slaughter of young men at a time when the total U.S. population was 34 million.”

It was a terrible sacrifice, and Lincoln bore the responsibility for it, he observed: “We’ll never know, but in my mind, it was Lincoln – with his intuition, his talent, his logic, his character and his vision – who took on the full responsibility for that conflict, because he was able to see ahead that if he did not, if someone did not, then the United States might split into two or four or six countries. We might have had the equivalent of the Balkan states on this continent.

“Abraham Lincoln is the American hero. He is what we think we are, or would like to be, in terms of character, shrewdness, intelligence, compassion and humour. He is the greatest American of all time.” ©