By Ray Bennett

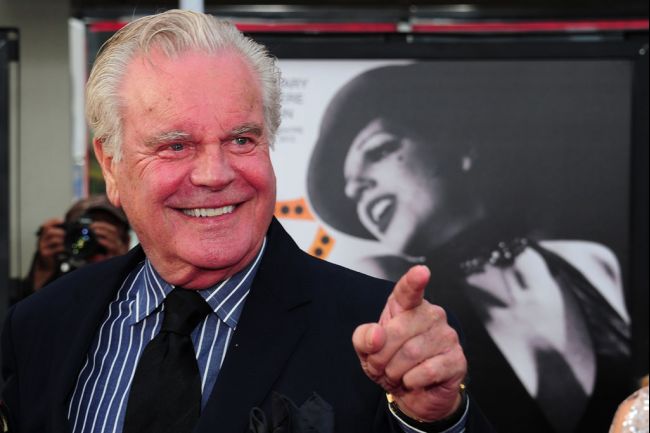

“What the hell kind of question is that?” It’s 1985 and I’m sitting with Robert Wagner, who turns 95 today, in his luxury trailer on the Warner Bros. lot where he was making the shortlived TV series “Lime Street”.

Two years earlier, I’d had lunch with him in that same trailer on the lot in Burbank where “Hart to Hart” was coming to an end. All around are photos of his family with many of his wife Natalie Wood (pictured below), who drowned at sea in November 1981 at the age of 43.

On the way there, in pouring rain, Wagner’s longtime PR man, George, says: “Please don’t ask him about Natalie or Jill. It’s not that he has anything to hide, it’s just that he has nothing he wants to say.” St. John was an old friend of the Wagners and she had been a steady companion since Wood’s death. (They would marry in 1990).

A sign on Wagner’s trailer door declares: Under No Circumstances Disturb Me. George knocks and we enter. Wagner is on the phone but he bids entry and George disappears. Wagner gets off the phone. At 53, he has become a little stout around the middle but he looks fit. His manner is stern until the smile comes and then there are few actors whose features are more appealingly friendly.

Wagner pours wine but not for himself: “Not when I’m working. I get sleepy.” He has seen me looking at the pictures on the wall but he chooses to remark on the trailer itself, which is the most luxurious you can imagine, and the moment is lost.

Two years later, we’re in the same trailer with the same photos of Wood but the mood is different because of the death of Samantha Smith (pictured below on the right), who was a co-star on the show. She had become famous at age 10 when she wrote a letter to then Soviet Leader Yuri Andropov and was invited to visit Moscow, which she did. She perished with her father in a plane crash just a month before I spoke to Wagner.

I choose my words carefully: I ask him if recent events had caused him to change his attitude toward mortality.

Wagner says, “What the hell kind of question is that?” and he ponders for a moment or two. He says, “So many people have had tragedy in their lives. I think you realise that when people that are very close to you are taken. Life constantly causes you to reassess just why you’re here. You realise that there are only a few things that are really important about being here, and that’s to be good to one another and to care for each other because no one has any control over what is going to be dealt to them in life. That little girl had a lot going for her and suddenly she’s gone. Her father, Arthur, was a wonderful man. They were quality people, believe me. So, yeah, it really makes you realise what’s important. My focus is my family. That’s always on top.”

I met Wagner several times and always found him to be a charming, self-deprecating and amusing gent, the kind who would write a note to your editor if he liked something you’d written. At a media event in 1987 for a TV movie titled “Love Among Thieves”, his co-star Audrey Hepburn was surrounded by admirers and it was impossible to get close. Wagner came to my rescue. We were chatting and he said, “Have you met Audrey?”. When I said no, he created a path through the scrum and so I met Holly Golightly, who was as unflustered and gracious you would hope.

The Detroit-born actor is probably known best today for his appearances on TV shows such as “NCIS” (with Mark Harmon, pictured below) and “Two and a Half Men” and the “Austin Powers” comedies and he’s always been easy-going about his career: “I came to Warner Bros. to try to break into movies and was signed to a picture with Jimmy Cagney called ‘The Grey Line’ or something like that. It was 1946-47, around there, but they had a big writers’ strike and it never got made. I went back to school but everything turns out for the best – you never know.”

In those days, all the major studios had scores of young performers under contract. Wagner worked steadily and it seems now that his career just sailed along in a wide range of pictures of varying quality. There was the title role in the period film “Prince Valiant” (1954), mountain-climbing adventure “The Mountain” (1956) with Spencer Tracy, espionage yarn “Stopover Tokyo” (1957) with Joan Collins, and romantic comedy “Say One for Me” (1959) with Debbie Reynolds and Bing Crosby.

He told me, “I always knew that this was what I wanted to do but I never knew if I would make it. I had a lot of people stroking me over the years — a lot of good people like Spencer Tracy and Elia Kazan who boosted me. I could have gone down. I had a lot of enthusiasm but I don’t think I was really so talented. I don’t think I’ve had all that talent within me that was bursting loose, that couldn’t wait to be seen and captured on the screen. I think I was really fortunate.

He told me, “I always knew that this was what I wanted to do but I never knew if I would make it. I had a lot of people stroking me over the years — a lot of good people like Spencer Tracy and Elia Kazan who boosted me. I could have gone down. I had a lot of enthusiasm but I don’t think I was really so talented. I don’t think I’ve had all that talent within me that was bursting loose, that couldn’t wait to be seen and captured on the screen. I think I was really fortunate.

“I know what that sounds like, but it’s the truth. It’s the truth. I mean, you look back at some of those pictures and you say, ‘Whew!’ But I kept going and in some of the stuff I was good, you know? Some of the stuff, I was O.K. I look back, and some of it wasn’t so bad for the time. I’ve had a lot of ups and downs. It’s not been particularly a case of not getting the parts that you want but of not working at all.”

In the early 1960s, Wagner moved to Europe and made four movies there – World War II epic “The Longest Day” (1962), Philip Leacock’s “The War Lover” (1962) with Steve McQueen, Vittorio De Sica’s “The Condemned of Altona” (1962) with Sophia Loren, Maximillian Schell and Fredric March, and Blake Edwards’s “The Pink Panther” (1963) with David Niven, Peter Sellers and Claudia Cardinale.

Back in the U.S., he found that he had been forgotten: “When I came back from Europe in the early ’60s, I had a soft spot for a while. I was out of work for a long time. The guy who pulled me out of it was Paul Newman in ‘Harper’ (pictured above). I think I loosened up a little bit in that film too. I’ve been really fortunate to have worked with people who have encouraged me, who’ve said, ‘Come on, you know it’s not gonna be that bad. Do it!’ I was sitting around the other day with a guy who started out in the picture business the same time I did and, I don’t know, it’s a real phenomenon: if you’re there and you keep going, if you just keep punching at it, somehow you stick around.”

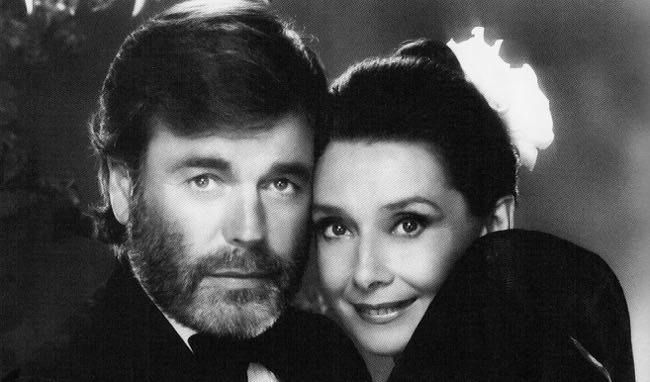

Later would come blockbusters such as “The Towering Inferno” (1974) with Steve McQueen, Paul Newman and William Holden and “Midway” (1976) with Charlton Heston, Henry Fonda, James Coburn and Robert Mitchum and TV movies including “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” (1976) with Natalie Wood and Laurence Olivier, “There Must Be a Pony” (1986) with Elizabeth Taylor, and “Love Among the Thieves” (1987) with Audrey Hepburn.

His TV series “It Takes a Thief” ran for just 66 episodes from 1968 to 1970 but was extremely popular and “Switch” ran for 71 episodes from 1975 to 1978. His biggest TV success was in “Hart to Hart” with Stefanie Powers, which had 111 episodes from 1979 to 1984 and returned in 1993 for a series of TV movies.

Wagner made a TV series in the United Kingdom in the 1979s for the BBC and Universal Pictures titled “Colditz”. A prisoner of war drama set during World War II, it costarred Jack Hedley, Richard Heffer and Edward Hardwicke, shown below standing behind Wagner and David McCallum. The series ran for 24 episodes in 1972-74 but the American actor appeared in just 14 of them.

He told me, “I liked the opening, the first year, but then we had a very difficult time. It started out as a kind of documentary but in the end they had the prisoners out sitting on deck chairs and they’d be singing away. The guys in Colditz never sang; they were starving to death. I said, ‘What is this, a bloody musical?’ I turned my back on the camera and walked out because they took something that could really have been great and put it in the toilet. The reason I reacted so strongly was because I really loved doing it, and I hated to see it wasted.”

Wagner said he had no great roles that he was dying to play, or the book that he wanted to make into a film: “There is no ‘Gandhi’ in my life. I think actors have to take what is dealt to them. You can spend an awful lot of time worrying about what you’d like to do but there’s a lot of good stuff just lying around on the ground if you peck at it long enough and make it happen.”

He was particularly proud of working with Olivier and Wood in the TV version of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” (pictured below): “I’ve often said I never thought something like that would happen to me in my whole life. A telephone call comes. I say, ‘What? Tennessee Williams? Larry Olivier?’ I mean, jeez! You never know what’s gonna come down the road.”