By Ray Bennett

LONDON – “It all goes by so quickly,” Gregory Peck told me. “It’s like a flash. Suddenly, one is in the home stretch and where did it all go? How did it flash by so fast?”

That was when the “To Kill a Mockingbird” Oscar-winner was aged 66. He was born 100 years ago today and he died on June 12, 2003. Among the hundreds of entertainment figures I have interviewed over the years, Peck (pictured above right with David Niven in “The Guns of Navarone”) is still the one who stands out, not least because we shared the same birthday nearly 30 years apart.

I met him several times including two long interviews at his palatial Holmby Hills residence in Los Angeles and he was always gracious, engaged and illuminating.

He was in virtual retirement when I first spent time with him in 1982 following an almost 40-year career at the top after he became a star in his second film, “The Keys of the Kingdom”, in 1944. He immediately had a steady stream of hits including “Spellbound” (1944), “Duel in the Sun” (1946) and “The Macomber Affair” (1947).

Peck often made social issues part of his work, most famously as Atticus Finch, the stalwart Southern attorney who defends a black man accused of rape in “To Kill a Mockingbird” (1962). In “Gentleman’s Agreement” (1947) it was anti-semitism, “Man With a Million” (1954) greed, “The Great Sinner” addiction, “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit” (1956, with Jennifer Jones pictured below) social conformity, “On the Beach” (1959) nuclear war, and “Captain Newman M.D.” (1963) mental health.

He was a longtime member of the U.S. National Council of the Arts; he risked the blacklist when he signed a letter in opposition to the House Un-American Activities Committee witchhunt in the 1940s; President Lyndon B. Johnson gave him the Medal of Freedom; President Richard Nixon put him on his enemies list; he campaigned against the Vietnam War and nuclear weapons; supported gun control; and the Motion Picture Academy gave him the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award.

In short, as well as a great movie star Gregory Peck was a good citizen although he downplayed that. “I never thought about it,” he told me. “I just did things I was interested in doing. I don’t think they made the world a better place. Maybe they haven’t done any harm. I’ve made movies that were said to have ‘social significance’ but there’s no way of knowing the effect on the audience’s thinking. Primarily, you set out to tell ’em a story and entertain them. If there’s a residue in the form of a fresh light on social issues – a bit of illumination – that’s the icing on the cake.

Peck volunteered that he had made some flops in his time but he quoted his old friend, the late actress Ruth Gordon: “She said, ‘Gregory, never discuss your failures. Why remind people?’ You’ve heard the old Sam Goldwyn line? ‘If people won’t go to the box office, you can’t stop them.’”

He offered “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” (1952), “Behold a Pale Horse” (1064) and “The Stalking Moon” (1968) as movies that he thought were fatally flawed but he said audiences thought so too.

“You don’t have to be very bright to recognise a well-done script when you read it,” he said. “But there were times when you spot flaws, some areas of the script where the tension let go or the interest lagged, and you think, well, we can fix this. We can do some clever rewriting and then with a certain clever way of playing the scene I’ll disguise its shortcomings. I’ll cover it with charm and the audience will never know it’s a bad scene. But they do. All you do is make it less bad; you don’t make it good.”

He pointed to “The Macomber Affair” (1947, with Joan Bennett and Robert Preston, pictured above), which he regarded as very nearly the best film of an Ernest Hemingway novel ever put on the screen except that the ending is flawed. In the story, a woman is allowed to go free after she murders her husband on safari but Hollywood’s censors at the time, the Hays Office, objected.

“We had to devise a compromise ending, which practically ruined what was a very faithful rendering full of Hemingway’s irony, toughness and lack of sentimentality. But there are many things in the film that I think are excellent.”

He was fond of “Pork Chop Hill” (1959), an uncompromising documentary-like war picture about a group of men who fight and die for a worthless hill in Korea. “To me, that is a good film but it did not have box office appeal,” he said.

Peck allowed that he was miscast as F. Scott Fitzgerald in “Beloved Infidel” (1959) and the film as a whole was not very good “but there are scenes of his despair and drunkenness that I think are some of the best things I’ve ever done.”

Over his long career, Peck also let some good roles get away. He turned down “High Noon” because he’d just had a hit Western – “The Gunfighter” (1950) – with a similar theme: “Gary Cooper was smart enough to take it and he did it beautifully. I probably couldn’t have done it as well but it was a surefire role.”

He said he rejected Frank Sinatra’s hit, “Von Ryan’s Express” because it came too soon after Peck’s blockbuster “The Guns of Navarone”. His consolation is that other stars also made mistakes. John Wayne turned down “Twelve O’Clock High” (1949), a smash-hit war film for which Peck won the New York Critics’ best actor award.

Peck made no apology for making films that were pure escapism. He pointed out that in “The Guns of Navarone” when he, David Niven, Anthony Quinn and the others are dressed in Nazi uniforms in occupied Greece during World War II running down a street chased by real Nazis “if we turn right, you know they’re going to turn left just like the Keystone Cops. They always do the wrong thing otherwise the picture’s over. At any point, the film could have been 10-minutes long. It’s more of a swashbuckler than a war picture. We knew what we were doing and it is on the verge of being tongue-in-cheek but it’s legitimate entertainment with a background of high adventure.”

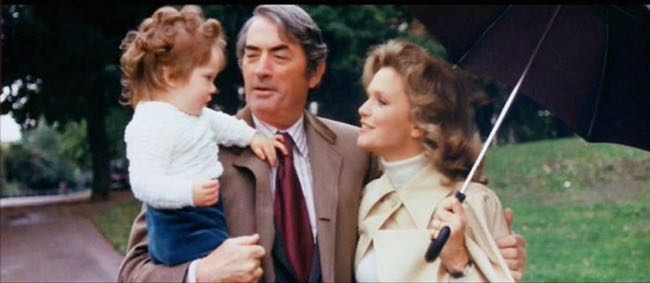

He felt the same way about his hit horror film “The Omen” (1976) as he felt the script was so well-calculated that he was sure it would be popular although the scale of its popularity surprised him: “All the business about 666 and the devil, I thought that was all nonsense but Lee Remick and I (pictured above) make a good team and perhaps make the audience care about us as all these terrible things happen. We didn’t believe any of it for a moment but it was pure entertainment of a very old form going back to the gothic novel and people sitting around a campfire seeing who can tell the scariest ghost story.”

Peck was proud of “To Kill a Mockingbird” and grateful for his Academy Award but he said: “When I first started, I think I was nominated four times in about five years and I didn’t win. I didn’t particularly think that I should have. I mean, people like Laurence Olivier made ‘Hamlet’, Fredric March made ‘The Best Years of Our Lives” and Ray Milland made ‘Lost Weekend’. I sat there and was not at all disappointed and nor did I think I was robbed.”

After “The Keys of the Kigdom” (1946), “The Yearling” (1947), “Gentleman’s Agreement” (1948) and “Twelve O’Clock High” (1950), he went 13 years without a nomination: “Then along came ‘Mockingbird’ but I wouldn’t have felt I was robbed then either. I mean, Jack Lemmon was up for ‘Days of Wine and Roses” and Peter O’Toole was up for ‘Lawrence of Arabia”. But apparently it was my turn.”

He said he was pleased that “To Kill a Mockingbird” had taken on a life of its own: “It’s played in junior high schools all over the country in their civics course; they read the book and watch the video and then they write essays about what the film meant to them. I have a bunch of them on my desk. That’s rather nice. It goes on and it probably will for a while. It’s probably not going to drop out of sight suddenly.”

Peck did some TV in the Eighties – “The Blue and the Gray” U.S. Civil War series and “The Scarlet and the Black” war picture are worth watching – and he had one more big picture, “Old Gringo” (1989) opposite Jane Fonda, but he accepted that his career at the top was over.

“It’s always been play to me. I felt lucky to be paid for what I would do for nothing if I had another means of income. It was a good career. One tends to forget the difficult times, the struggles, the clashes of temperament, the futile attempts to make a good film out of a bad script. I’ve been a very lucky individual because I’ve had many times when I could not ask more from life.”

He was delighted that he was able to play his hero Abraham Lincoln onscreen even though it was a cameo in “The Blue and the Gray” and he didn’t claim it was a great performance.

He said, “It’s a good reminder to Americans of what kind of people preceded us and what they did for us; that it’s worth preserving and that, if there are changes that have to be made to preserve it, then we’d better get busy and make those changes.”

Peck paused and laughed. “I think I’ve veered off into cracker-barrel philosophy. I think I’ve spoken my own eulogy.”