By Ray Bennett

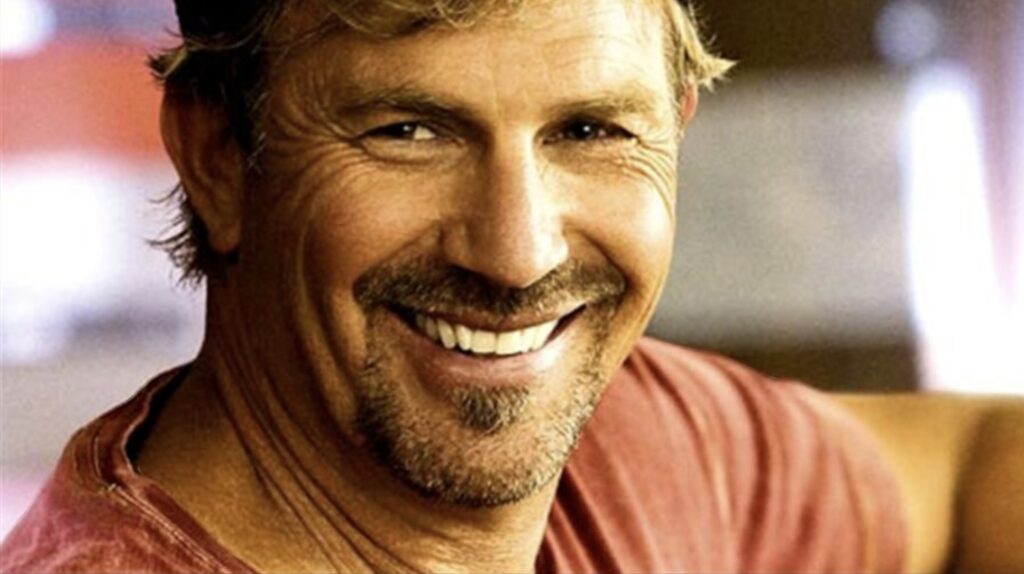

Martin Shaw, who turns 80 today, is known best for playing TV coppers in “The Professionals” and “Inspector George Gently” but he also has had a long stage career in roles from Stanley Kowalski to Lord Goring to Elvis Presley, and he loves to fly.

The Birmingham-born actor is regarded as a prickly interview subject but when we chatted in 2011 for a story in Cue Entertainment, we got along fine, possibly because we’re about the same age.

Shaw won international fame as Doyle, a young action hero in tight jeans with his hair in a huge perm alongside Lewis Collins as Bodie in the action series “The Professionals”, which ran from 1977 to 1983. The actor made clear at the time his displeasure with “The Professionals” and he had no desire to talk about it now.

But when I asked him if Doyle might have grown up to be George Gently, the shrewd senior officer with short steely hair and a manner to match, he said: “Good question. It’s hard to answer because Gently is a real person, a real character, and Ray Doyle wasn’t.”

It couldn’t have happened because “The Professionals” was very much a 1970s show while “George Gently”, which commences its eighth season on BBC One this year, is set in the 1960s. Shaw said he was drawn to the role because of the way he was created by writer Peter Flannery in the pilot script.

Gently is a policeman who has been hardened by war and his wife’s murder: “George is an old-time copper. He fought in World War Two and he’s a very tough, seasoned fighter. He knows about hardship and has seen tough times.”

It was intended to be much darker than the series has become, Shaw said executives saw potential in the relationship between Gently and the younger policeman played by Lee Ingleby so it was “softened” for broader appeal: “The pilot ended with the baddie, a very mad man played by Phil Davis, being hanged. The priest said, ‘‘Do you have any last words?’ And he said, ‘Yeah. Make it fucking slow.’ Blackout. That was how dark the pilot was, but it became a different show.”

Shaw said the 1960s setting has allowed the show to delve into social and cultural issues of the time such as police brutality, capital punishment, racism, wife beating and abortion: “In the UK, it seems to me that necessarily everything stopped during World War Two. From 1939 to 1945, everything stopped. Then, from ’45 to ’60, everything was still at a standstill because we were in recovery. And then, suddenly, there was more than 20 years of movement and progress that developed in about 18 months.”

Before “George Gently”, Shaw had the title role in the legal series “Judge John Deed” for six seasons from 2001 and played writer P.D. James’s forensic detective Adam Dalgleish in “Death in Holy Orders” in 2003 and “The Murder Room” in 2005: “Interestingly, I’ve played more homosexuals than I have cops. But we make a lot of cop shows. It’s just what gets noticed. It’s either an observation or an indictment; it depends on your point of view. You’re either gonna be a copper, a lawyer or a doctor. That’s it.”

As a young man, he was at drama school with innovative artists such as French director Michel St. Denis, British director Peter Brook, and playwright Charles Marowitz. His early work was at the Royal Court Theatre, and with leading theatrical directors William Gaskill and Peter Hall and future filmmakers Roman Polanski and Lindsay Anderson (“O Lucky Man”): “My start, long before ‘The Professionals,’ was with all these people and it was such an exciting time to be an actor.”

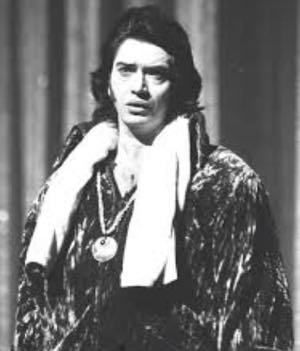

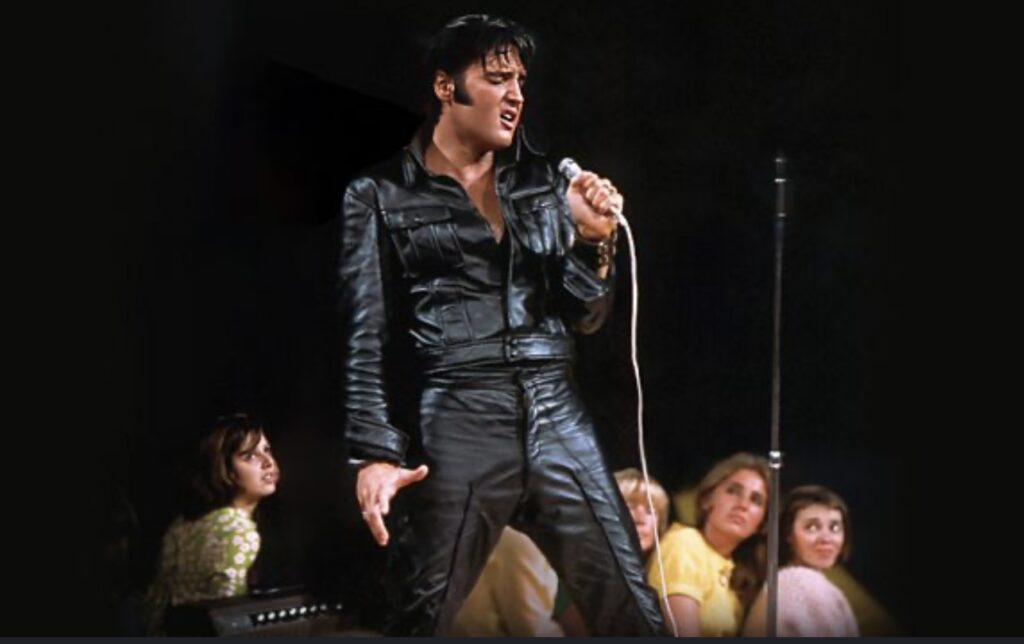

He credited a 1974 run in London’s West End as Stanley Kowalsky in Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire” as a major breakthrough and in 1985 he played Elvis Presley in the long-running play “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” by Alan Bleasdale. Shaw was an Elvis fan but he said the show was a challenge: “I used to sit up until 3 in the morning watching the documentaries … stop … freeze frame … play bits back … and then learn my lines … get up at 6 to learn more lines. It was hard bloody work. There were so many expectations but I was constantly reassured both by [writer Alan] Bleasedale and [producer Bill] Kenwright, and the director Robin Lefebvre, who said, ‘We don’t want an impersonation. This is a performance. Get on the inside.’ It sort of evolved by osmosis and I got to be like him anyway. Then we got the Evening Standard Award, so it was obviously well received and well respected.”

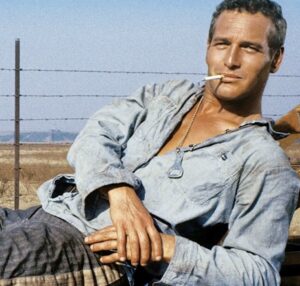

Among his greatest stage successes was his appearance as Lord Goring in Oscar Wilde’s “An Ideal Husband,” which was directed by Peter Hall and ran on Broadway for 307 performances from April 1996. Shaw was nominated for a best actor Tony Award and won the Drama Desk Award for outstanding featured actor in a play. I saw him on the West End stage at the Apollo Theatre on Oct. 11 2010 in Clifford Odets 1951 “The Country Girl” and he and co-star Jenny Seagrove were outstanding in roles played in the 1954 movie by Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly, who won an Oscar.

A keen aviator who gained his pilot’s licence more than 20 years ago, Shaw has made several documentaries for the BBC about military exploits involving planes such as “Aviators” (2006), “Dambusters Declassified” (2010), and “Jericho” in 2014.

His interest in flying started with his father as far back as he can recall: “I was born and raised in Birmingham no more than a mile or two from Castle Bromwich, which was where they made and assembled and tested Spitfires and Lancasters. From my earliest memories, the sky was always full of aeroplanes. We went flying in an old biplane from Castle Bromwich for 5 bob each (5 shillings in old English money). It just started from that.”

A thoughtful man who prefers country solitude to city life, he reflected on the passage of time. For the “Dambusters” documentary, he navigated a plane as it flew at low level toward the dam of the Möhne reservoire, which was the target of the May 1943 raid by RAF personnel from Australia, Canada and New Zealand. When they landed, he did some pieces to camera and interviewed people at the dam: “I found that incredibly moving; far more moving and disturbing than I’d expected because it was such a peaceful and a pretty place. To imagine that I had been born at the end of a conflict with all of these lovely people around – pushing prams, and having picnics in this beautiful place – and I was part of a race that had triumphantly destroyed this area and killed thousands of people … we all talk very glibly about the futility of war but it’s never been more powerfully brought home to me than being underneath the Möhne Dam and surrounded by lovely people on a beautiful spring day. Time just makes it utterly and completely nonsensical.”

He said he is glad, though, to have lived when he did: “We’ve got the vocal memory; we’ve got the word of mouth. I think we’re possibly the last generation to have that because people after us have got these things (points at my digital devices). My grandmother used to tell me about the Wild West Show. She saw the Wild West Show in Birmingham at Bingley Hall. She saw Buffalo Bill and Chief Sitting Bull. She used to tell me when I was a little boy: ‘He rode up on a big white horse and he had a big white hat and a long pointy yellow beard and long yellow hair, and he reared up on the horse and said, ‘Look over there, ladies and gentlemen, and all the Indians came out led by Chief Sitting Bull.’ And I’ve heard that. It’s living.

The “Dambusters Declassified” and “Jericho” documentaries are available on YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HAlaPEfcX2Q and

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=35qsu9HsYos

Thinking of my Dad on New Year’s Eve

By Ray Bennett

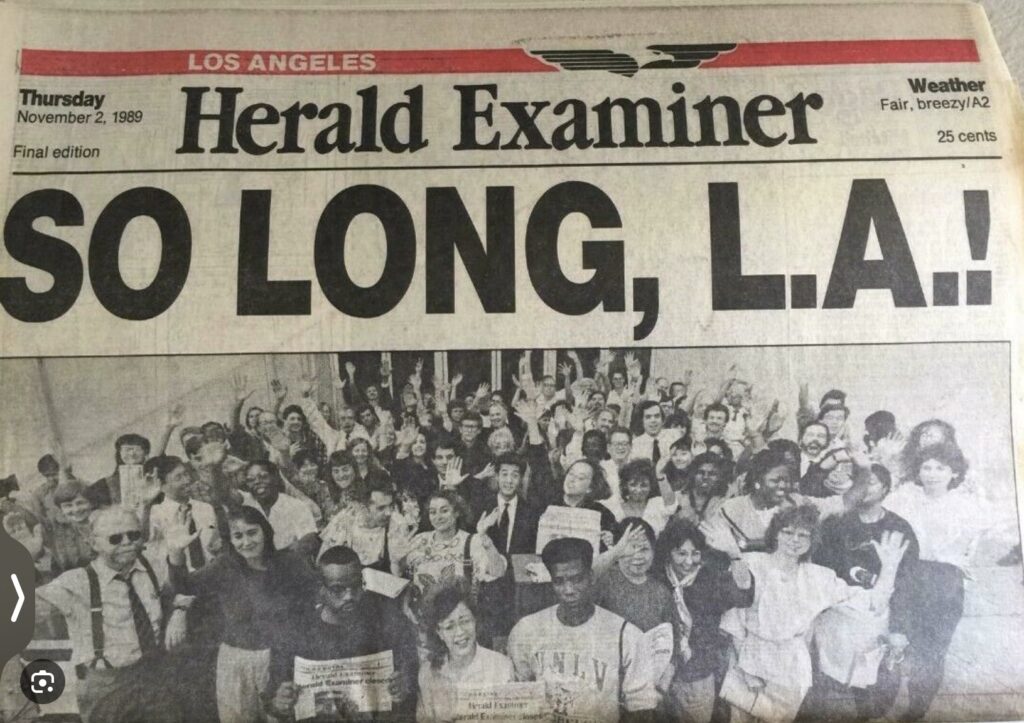

My late older brother Roland phoned from England on New Year’s Eve to tell me that our Dad, Alexander Bennett, had died. I thought it was 35 years ago but another year has slipped by and I see that it’s 36. December 31, 1988. I was living in Franklin, Tennessee, just south of Nashville, alone again, naturally. Ro said Dad had been feeling chipper but that morning he put on jacket and tie as always to walk to the shops but soon returned complaining of chest pains. He had been suffering from a touch of angina. He sat down in his favourite armchair holding his wife’s hand then said “Oh, oh,’ and passed away.

Our family home had been a flat in a converted railway station in Ashford, Kent, until Mum, Winifred, died aged 62 on the same day as Elvis Presley. Sometime after, Dad moved back to his native Devon where, aged 80, he married a sweet and kind widow named Wink and lived with her in a charming bungalow in Budleigh Salterton. We had known her for years as she was the sister of our beloved Aunt Doffy, who was married to Dad’s brother Fred. I spoke to Wink and she said she was okay and grateful that ‘I had seven years with a wonderful man.’ She had two sons from her first marriage who would take care of her.

My younger brother Richard (on the left in the photo next to Ro, Dad and me) joked on the phone that Dad had gone to give god a hard time. We laughed because Dad would have laughed at that as he had no truck with religion. He had a remarkable life’s journey. Son of a farm labourer with nine siblings, he journeyed in his teens during the First World War to faraway Kent to work on British Railways. Labouring as a plate-layer – called a gandy-dancer in the early days of railways in the United States – he went to night-school, won promotions to white-collar positions and ended up as Chief Inspector of the Permanent Way. I never heard the word ‘profit’ growing up. Dad’s only concern was keeping passengers and crew safe as they rode the rails.

Ro said Dad had accepted fate, saying, ‘I had a good innings; I don’t want anyone to be upset.’ It was typical of a hard man with a soft heart, enquiring mind and whimsical sense of humour. An avid reader and skilled gardener, he voted Labour all his life but trusted no-one. When a party member rang our door bell seeking to recruit me, Dad gave him short shrift. He despised Margaret Thatcher, who worked to destroy unions in the Eighties, saying it reminded him of the Twenties when Winston Churchill sent out armed police on horseback to put down protests during the General Strike. ‘We were beetles,’ he said, ‘ and they wore heavy boots.’

Dad taught me an important life lesson when I was 10. For a primary school assignment, I asked him to tell me how the railway worked. He gave me a broad outline and then some specific details always speaking extemporaneously. He knew the railway inside out from the bottom up.

Dad took me aboard a steam locomotive, which was exciting, and inside a railway signal box. A tall boxy structure sitting at a junction, it had steps leading up to a large room filled with rows of multi-coloured, four-feet tall levers that the signalman used to control sets of points on the tracks. We walked along the line, stepping over the wooden supports called sleepers, to see the points – tapered steel blades, movable rails. Each pair was governed by a lever in the signal box.

I thought that being on a train was simple: you boarded, enjoyed the ride and when it reached your destination, there you were. Seeing that signal box and its control of the switching points showed me it wasn’t that simple. On a train, with the switch of a lever, you could end up in London, Birmingham, Edinburgh or Paris. Later, I discovered poets who wrote about crossroads in their lives and taking paths less traveled. They made it look as if were always by choice. The signal box gave me my first clue that in life you might move a lever yourself or the points would be switched by others. When that happened, there was no knowing where you might end up. It depended upon who pulled the lever.

I don’t put too much stock in it but Dad never celebrated New Year’s Eve. Neither do I.