By Ray Bennett

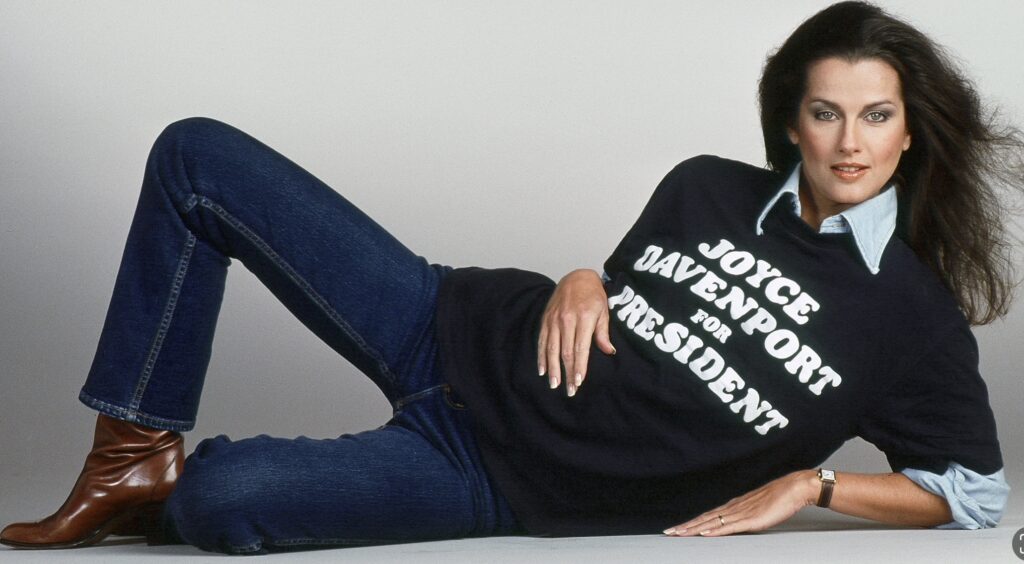

LONDON – I had the tee-shirt in the photo above made and gave it to Veronica Hamel on the set of the hit American television cop series ‘Hill Street Blues’, in which she played attorney Joyce Davenport. She loved it. ‘I wear it to work,’ she told me. ‘They figure I’ll do a better job than anybody else.’

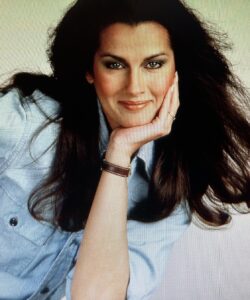

Veronica Hamel, who turns 80 today, was one of the most beautiful women on TV in the 1980s, an era of glamorous women on the home screen. Formerly a model, she accepted her beauty with grace and self-effacement. Daniel Travanti, who played Capt. Frank Furillo on the show, Davenport’s lover (pictured with Hamel below), told me, ‘Can’t help but be impressed by her because she’s obviously so beautiful. She’s lived with that and made adjustments. She’s so simple and real about it. She’s very quick to let her hair down. Never gives the impression of being unreachable. She’s not self-protective. If the director wants something messy or foolish, she does it. She doesn’t worry about being lady-like although she’s never not.’

Steven Bochco, who created the series with Michael Kozoll, told me they hired Hamel because of her combination of attributes. ‘Physically, she’s just exquisite and she conveys a tremendous intelligence, a kind of really warm authority,’ he said. ‘The role is a really strong, bright, talented, ambitious character with her own set of complex needs and a great sense of humour. I tell ya, Veronica is a remarkably sexy woman because of that. She is sexy in a way that other women in television are not, because she is real.’

Steven Bochco, who created the series with Michael Kozoll, told me they hired Hamel because of her combination of attributes. ‘Physically, she’s just exquisite and she conveys a tremendous intelligence, a kind of really warm authority,’ he said. ‘The role is a really strong, bright, talented, ambitious character with her own set of complex needs and a great sense of humour. I tell ya, Veronica is a remarkably sexy woman because of that. She is sexy in a way that other women in television are not, because she is real.’

That was exactly how she appeared offscreen too when I interviewed her for a cover story in Canadian TV Guide. I liked her immensely. Over a long, leisurely lunch, just the two of us in a quiet corner of the CBS Studios commissary, we talked about her successful career as a model and transition to acting. I told her that she had a terrific sense of humour. She gave me a look. “How do you know that? You don’t know me.’ I mentioned seeing a lot of kidding on the set. ‘Yes, well, that is something I enjoy in people,’ she said. ‘I think it’s one of the nicest qualities that people have, their humour, particularly not to take yourself too seriously.’

I said I also thought she could be a rascal. She gave me another look: ‘Oh, I can be worse than that. That’s a euphemism. You’re tippy-toeing around here. Well, I’m not gonna let you in on anything devastating. Acting is a much crazier world than modelling but at times people will write to me recalling certain things I’ve done, which I find fascinating but I won’t tell you about.’

I said I also thought she could be a rascal. She gave me another look: ‘Oh, I can be worse than that. That’s a euphemism. You’re tippy-toeing around here. Well, I’m not gonna let you in on anything devastating. Acting is a much crazier world than modelling but at times people will write to me recalling certain things I’ve done, which I find fascinating but I won’t tell you about.’

Born in Phaldelphia, daughter of a furtniure refinisher, with one sister, at 17 she began a modelling career that lasted for ten years. She expressed no qualms about it. ‘I think models are very underestimated for the talent – possibly a better word is stature – that it takes to stand in front of a camera and grab someoe’s eye. There is a thought process there, an attitude. To fill that space and be exciting, it isn’t just beauty alone that can do that.’

She studied acting in New York and did off-Broadway and dinner theatre and finally decided to quit modeling. Moving to California, she did the rounds of TV series before ‘Hill Street’ came along. I visited her a few times on the set and we spoke on the phone. She always had something unexpected and interesting to say having nothing to do with acting or show-business including an anecdote from her modelling career.

‘I did a job in Vienna at a fancy hotel and I was dressed in the most exquisite designer gown,’ she said. ‘It was wine velvet with a sable hem. My hair was up with various hairpieces and flowers and whatnot. I just couldn’t stand myself. I didn’t want to take it off. I wanted to parade around and do that forever. When we were finished shooting, I asked the photographer and client if I might go down and have cocktails in this dress. I was just too wonderful. They had this marvellous, marvellous staircase with a huge chandelier in the foyer. People were gathered for cocktails and I made my grand entrance at the top of this staircase, so terribly impressive, me with my sable and velvet and all the trimmings. As I proceeded down the stairs with the brass banisters – they had a red carpet, naturally, that was the least they could do for me looking so wonderful. Everybody looked up. I took a deep breath and there I was, the centre of attention. It was too, too much and I was too wonderful. It served me right. There’s always that little person up there saying, wrong! I tripped, slid down on my fanny, my skirt going up in a rather unattractive, unladylike manner. Down several stairs and there I sat, my hair falling to the side with everyone staring. I just started laughing. That’s it. Whenever you think you’re there and can’t stand yourself, duck! That taught me a huge lesson. I don’t think I’ll ever forget that.’

‘I did a job in Vienna at a fancy hotel and I was dressed in the most exquisite designer gown,’ she said. ‘It was wine velvet with a sable hem. My hair was up with various hairpieces and flowers and whatnot. I just couldn’t stand myself. I didn’t want to take it off. I wanted to parade around and do that forever. When we were finished shooting, I asked the photographer and client if I might go down and have cocktails in this dress. I was just too wonderful. They had this marvellous, marvellous staircase with a huge chandelier in the foyer. People were gathered for cocktails and I made my grand entrance at the top of this staircase, so terribly impressive, me with my sable and velvet and all the trimmings. As I proceeded down the stairs with the brass banisters – they had a red carpet, naturally, that was the least they could do for me looking so wonderful. Everybody looked up. I took a deep breath and there I was, the centre of attention. It was too, too much and I was too wonderful. It served me right. There’s always that little person up there saying, wrong! I tripped, slid down on my fanny, my skirt going up in a rather unattractive, unladylike manner. Down several stairs and there I sat, my hair falling to the side with everyone staring. I just started laughing. That’s it. Whenever you think you’re there and can’t stand yourself, duck! That taught me a huge lesson. I don’t think I’ll ever forget that.’

Another time, we were talking about life choices in terms of a career and she brought up someone who has only now become well known to a lot of people: Robert Oppenheimer. She had seen John H. Else’s 1981 documentary about him, ‘The Day After Trinity’ and said, It was fascinating seeing him as a young man in his baseball hat in his bunker as the first H-bomb went off. And it was very strange watching him as an old man reflect on his life and work, his mentality, the brain he was given. They asked him how did he feel watching the first bomb go off. Today, we have bombs that make that look like spit, which is really frightening. He sat in his chair and he had tears in his eyes. It was so wonderful. As the camera zoomed in ever so slowly, he said, ‘I thought of a Hindu poem, “Now I have become death, the destroyer of worlds.” I just burst into tears looking at this old man’s face and thinking his intellect and mind went for destroying worlds. What an incredible thing to come out with. Whenever I think I should be doing something worthwhile, medicine or something or this or that, here was a man who spent his life – one of the finest minds we’ve ever known – and at the end of his life he was so torn about why he was here. Maybe I am doing something much more worthwhile than I know; at least less destructive.’