By Ray Bennett

LONDON – In a remote desert town in South Australia in 1958, a 9-year-old girl is found raped and murdered. On the flimsiest evidence, local police almost immediately arrest a young Aboriginal man and obtain a confession. Only the efforts of a stubborn, inexperienced Adelaide lawyer stand between the accused and the hangman.

Craig Lahiff’s sturdy courtroom drama, based on real events, follows a predictable path and is unlikely to make substantial gains at the box office but it’s a laudable effort and certain to please fans of Robert Carlyle.

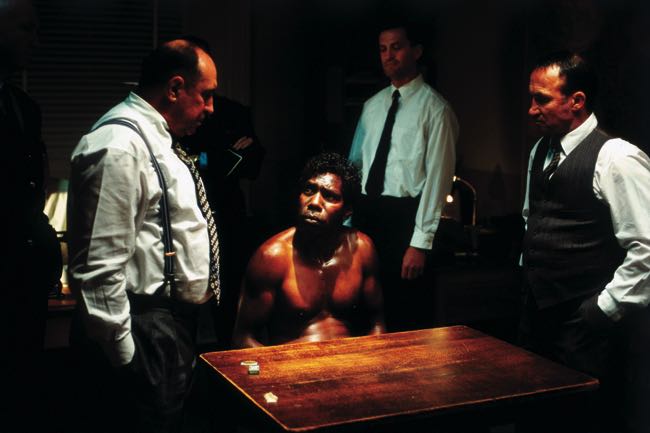

The “Full Monty” star plays the obstinate lawyer David O’Sullivan whose dislike of the antiquated British-based Australian judiciary drives him to take seriously a case he’s obliged to take without a fee. He quickly learns that the Aboriginal Max Stuart, played with unsentimental grace by David Ngoombujarra, is illiterate and put his mark on a confession he couldn’t read.

When it turns out that Curtis was in police custody for being drunk at the time the murder took place, it appears a dismissal is inevitable. But the pathologist changes her mind and fixes the death outside the timeframe of his alibi.

Only when he’s sent for trial does Curtis claim that the police beat him in order to obtain the confession. By now, O’Sullivan is going head-to-head with a pillar of the judicial establishment, Roderic Chamberlain, played with typical elegance and power by Charles Dance.

More evidence emerges that tends to suggest Curtis’ innocence when a compassionate priest becomes involved but he is convicted and sentenced to hang. O’Sullivan’s fight to win appeals goes all the way up to a Royal Commission, putting Curtis near the hangman’s door seven times while the local newspaper, published by one Rupert Murdoch, gets on the bandwagon to defend him.

Ben Mendelsohn plays the young Murdoch as a callow opportunist and the film suggests his enthusiasm for the campaign swiftly ended when he was threatened with prosecution for seditious libel.

The film dips a toe into the role of newspapers influencing trials but drops it as topic to focus on O’Sullivan’s class struggle with Chamberlain. Screenwriter Louis Nowra and director Lahiff develop that theme effectively and take the trouble to invest Chamberlain with considerable human dimension.

There is a clever scene in which the aristocratic hopeful for the Chief Justice’s chair snarls out his view of the case to his wife and their genteel friends, sparing them no brutal detail of the rape and murder as he believes they happened.

O’Sullivan runs into almost uniformly supercilious representatives of the British legal establishment, however, all with condescending stares and snooty voices. But the lawyer’s dependence on his reluctant but loyal partner, played sympathetically by Kerry Fox, is well drawn and at no point does Carlyle allow himself to showboat. His is a fully professional performance that shows no strain from the fact that he carries the film on his shoulders.

Lahiff shows little visual flair and the film will fit nicely on the small screen. It’s a grim tale not told in a grim way; an honorable argument not angry enough. A bit more of Chamberlain’s superb self-belief might have given the piece a lot more power.

Opens: UK Jan 9 (Tartan Films); Cast: Robert Carlyle, Charles Dance, Kerry Fox, Colin Friels, Ben Mendelsohn; Director: Craig Lahiff; Writer: Louis Nowra; Director of photography: Geoffrey Simpson; Production designer: Murray Picknett; Costume designer: Annie Marshall; Editor: Lee Smith; Producers: Helen Leake, Nik Powell; Not rated; running time, 100 minutes.

This review appeared in The Hollywood Reporter.