By Ray Bennett

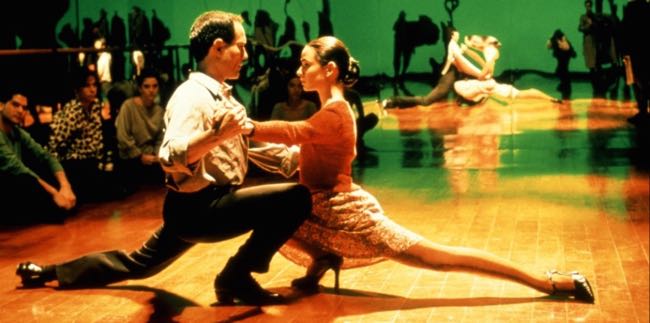

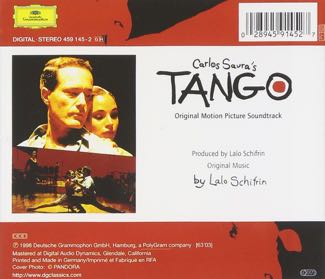

Argentinian composer Lalo Schifrin, who has died aged 93, is known for his concerts, recordings, film scores such as “Bullitt”, “Cool Hand Luke” and “Dirty Harry” and TV shows such as “Mission: Impossible” and “Mannix” but one of his most treasured works was for Carlos Saura’s Oscar-nominated musical “Tango”.

“I feel very proud of being involved in that movie,” Schifrin told me in 1998 just before the film had its international premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Directed by Carlos Saura and shot by three-time Academy Award-winning cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, “Tango” meant so much to the composer because of the way the film connected music and film to the terrifying period of dictatorship in his homeland.

During the years of repression in the Seventies when the military and Argentinian dictators were in power, they kidnapped people for any reason, he reminded me.

“It started as a civil war but then, like all these things, it got out of hand and the military became very fascistic and very brutal. Constitutional rights were finished,” he said. “They were torturing people and they were playing tangos very loud in order to cover up the screams of the victims. They used electric prods and any method of torture and they killed many people. They calculated that 40,000 to 50,000 people disappeared in that period. In the movie, there is a tango that I did with the Philharmonic Orchestra of Buenos Aires titled ‘The Repression’. It’s a very, very strong moment.”

He contributed around 45% of original music for “Tango”. Source music was used for the ballroom dance scenes but Schifrin supervised the orchestration of the traditional tangos and one titled ‘Calambre’ by Ástor Piazzolla, with whom he had performed: “I did the score in the rhythm of the tango. The movie is a musical without songs as Carlos tells the story through dance. It’s not a documentary; he tells a story through the tango.”

He contributed around 45% of original music for “Tango”. Source music was used for the ballroom dance scenes but Schifrin supervised the orchestration of the traditional tangos and one titled ‘Calambre’ by Ástor Piazzolla, with whom he had performed: “I did the score in the rhythm of the tango. The movie is a musical without songs as Carlos tells the story through dance. It’s not a documentary; he tells a story through the tango.”

Schifrin explained that what happened to tango music in that period in Argentina was similar to the swing era when bands led by Glenn Miller, Harry James, Artie Shaw and Duke Ellington were popular: “They were playing for dance but they sounded different. The same thing happened in Argentina for tangos. Each one of the bands had a style. Some of the arrangements we could retrieve but very few. The others had to be reconstructed from records. I had to supervise the hiring of different orchestrators and ensure that the arrangements were exactly the same style as those orchestras.”

He recorded the score in Buenos Aires, he said, because the best tango musicians were there: “I used very good soloists, in comparison, going back to jazz, with Charlie Parker. I had the best bandoneon player, Nestor Marconi. That’s the instrument that Piazzola played. It’s a concertina but it’s big and very difficult to play. It was invented in Germany in the 16th century. In poor churches, they couldn’t afford an organ so they had a portable bandoneon. I had some of the best violin players, all-stars. There’s a pianist named Horatio Salgan who is like an Argentinian Oscar Peterson. He’s 80 years-old and he not only plays but he appears in the movie.”

Schifrin’s musical reputation reaches far beyond Hollywood. Born in Buenos Aires into a musical family, he received classical training there and in Paris and then ventured into jazz in Europe and South America. He performed with Piazzolla and later Dizzy Gillespie, Xavier Cugat and Johnny Hodges. His own works range from concert music to jazz and he has recorded with artists ranging from Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan to Placido Domingo and Julia Migenes.

Schifrin’s musical reputation reaches far beyond Hollywood. Born in Buenos Aires into a musical family, he received classical training there and in Paris and then ventured into jazz in Europe and South America. He performed with Piazzolla and later Dizzy Gillespie, Xavier Cugat and Johnny Hodges. His own works range from concert music to jazz and he has recorded with artists ranging from Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan to Placido Domingo and Julia Migenes.

He has written many commissioned works and arrangements for orchestras around the world and for such events as the Three Tenors World Cup celebrations in Rome, Paris and Los Angeles. In 1996, he arranged and conducted a major concert in France to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the first cinema images by the Lumiere Brothers. Some of the tree-hour concert is available on a CD titled “Film Classics”.

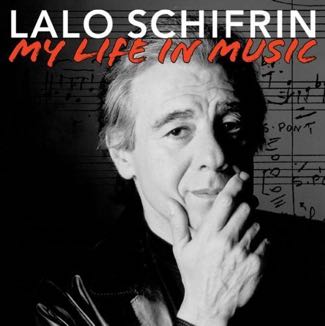

With four Grammy Awards and six Oscar nominations to his credit, many of Schifrin’s recordings are available on his wife Donna Schifrin’s record label, Aleph Records, and via his own website.

He chooses not to name a favourite: “I like all of them because it’s like asking a father which of his children he likes better.”

He chooses not to name a favourite: “I like all of them because it’s like asking a father which of his children he likes better.”

Schifrin also declines to categorise film music. He told me, “In the whole history of talkies, since sound started in movies, you cannot talk about the state of the art in terms of music because it changes according to the movie and the composer and the style. Sometimes B-movies have great music, so it depends. I don’t think you’ll ever be able to make a generalisation because movies have one aspect that is artistic and the other aspect is industrial. It is an industry and because of that, it depends on fads – wide lapels, you know? Basically, the composers who have personality, they do what they do. Bernard Herrmann, when he did ‘Psycho’, he was not going by fads, he was inventing things. The best composers are the ones who try to make a contribution by inventing things.”

The photo of Lalo Schifrin at the top was taken when he was awarded BMI’s Max Steiner Film Music Achievement Award for his outstanding contributions to film music at the Wiener Konzerthaus in Vienna on October 22, 2012. Afterwards, David Newman conducted the Vienna Radio-Symphony Orchestra in a selection of Schifrin’s compositions during the annual Hollywood in Vienna Concert, which celebrates classic and current masterpieces of film music.