By Ray Bennett

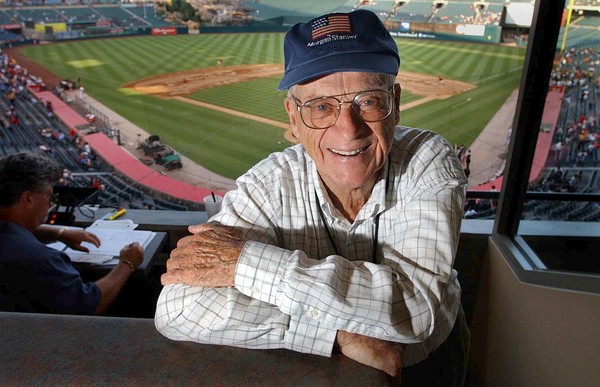

LONDON – The first baseball game I ever saw was at Tiger Stadium in Detroit in 1970 and a bonus of living across the river in Windsor, Ontario, was that I was able to hear the club’s longtime radio play-by-play man Ernie Harwell, who died five years ago today at 92.

Ernie Harwell’s lazy Georgia drawl was pure sunny afternoons and balmy evenings in the bleachers, peanuts and beer, stolen bases and home runs. It was as much a part of the sounds of Detroit Tigers baseball as the crack of bat on ball, the cries of the hot dog vendors, the cheers and the groans.

When he said “Strike!” on the radio it had all the urgency and finality of a fastball smacking into the catcher’s mitt. When I interviewed him 40 years ago, Harwell had been the voice of the Tigers on WJR-Radio for 15 years following stints over 12 years with the Brooklyn Dodgers, the New York Giants and the Baltimore Orioles. At first, he did TV as well but then focussed on radio.

He covered 162 games at home and away each season and he would not retire until 2002. He and his wife Lulu raised four kids and in his spare time Harwell liked to write songs. Several were recorded by name artists. B.J. Thomas sang his “I Don’t Know Any Better” on his greatest hits album and NBC gave a lot of play to a song he wrote about Hank Aaron: “Move Over Babe, Here Comes Henry”.

Baseball remained his great love: “The only hassle I ever had with a player was with Leo Durocher when he was broadcasting out of New York City, and not really then. We were on a train and I was reading the paper. He flipped the paper in my face and he’s not the kind of guy you can let get away with something like that or he’ll never stop. We huffed and puffed and rolled around a bit and were both glad when it was all over.”

One of his duties for a while was to pick the singers to sing the national anthem at games. One he chose during the 1968 World Series was Jose Feliciano and when the blind Puerto Rican’s original version created a ruckus, Harwell caught the flak and lost that job.

Among the good times, he recalled handling the third playoff game on Oct. 3 1951 when Bobby Thompson’s home run helped the New York Giants beat the Dodgers. That was the first sports series seen coast-to-coast and Harwell did the play-by-play. Then, of course, there was the Tigers world series in 1968.

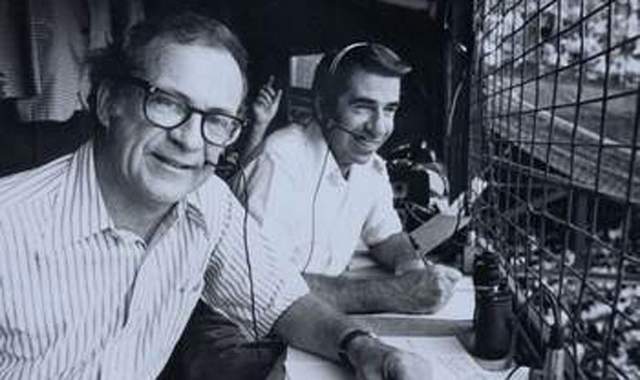

He sat through games of up to 22 innings in the tiny cage booth up behind home plate at Tiger Stadium. Most of the seats were flat and hard there but he had a well-worn armchair. Fellow commentator Paul Carey (pictured with Harwell above) did the radio engineering work and maintained touch with WJR. An old carpet kept the wind from blowing through the floorboards, two weathered overcoats hung on the wall and Harwell kept an electric blanket there just in case.

The game was paramount, not the announcer, he said: “But you can’t just give them ‘ball one, strike one’. You have to humanize the game. In 162 games, you have to be what you are. If you have a certain attitude, if you’re critical, say, then be critical. I’m not too critical. If there’s an error, I’ll say it’s an error and let it go at that. In football, an error can get lost – even the coach might not see it until he looks at the film the next day. In baseball, it’s right out there. It’s enough to say the ball went through the guy’s legs. You don’t have to say he made a lousy play – everyone knows that.”

It was up to the fans to judge if he was fair, he said: “I try to be neutal in favour of the Tigers and I can’t be gloomy when they lose. These guys on the field aren’t crying in their beer or anything. They’ve still got to show.”

Like all sports commentators, Harwell said basically the same thing over and over again but somehow he found a new way to say it. In just a few words, he captured the mood of the game, the character of a player, his stance. The Tigers’ Joe Coleman wasted no time when he was pitching and you’d hear Harwell snap away fast to a commercial in order to be back for the next pitch.

When a foul ball flew into the crowd, he’d often say something like, “A man from Lima, Ohio, will take that one home.” He had no idea, of course, but after the club stopped mentioning names for birthdays and anniversaries during game, he used that gimmick to greet fans from out of town.

When it came to the game, he was a traditionalist. Salaries were too high, he told me between plays, and there were too many conferences on the mound, but he did not wish to change the game: “One of baseball’s strengths is that it hasn’t changed much.”

That was Ernie Harwell’s strength, too, as he spoke into a tiny head mike: “There’s a cool breeze at Tiger Stadium tonight, a fine night for baseball. Coleman pitches. It’s a fastball above the knees. Strike!”

This is adapted from a story I wrote for The Windsor Star, published on Aug. 23 1975.