By Ray Bennett

LONDON — The appearance of the Grim Reaper at a dinner party is social death, as Monty Python once demonstrated. It’s true even when, as in Edward Albee’s darkly comic and highly entertaining “The Lady From Dubuque,” that unwanted creature takes the form of Maggie Smith.

Legendary editor Harold Ross declared at the founding of The New Yorker that the urbane magazine would not be edited “for the old lady from Dubuque.” With typically biting humour, Albee took the phrase for the title of a play about the angel of death.

It’s a theatrical but bitterly funny and moving play about raging at the dying of the light. Directed with flair by Anthony Page, the production reportedly is headed for Broadway where the play was spurned on its debut in 1980.

Albee (“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” “The Goat”) specializes in exorcising modern urban demons with shrewd observation, devastating exchanges and great jokes, and while this play does not rank with his finest, it is well worth a revival.

It lasted just 12 performances on Broadway in 1980 although it was directed by Alan Schneider, who had won a Tony Award directing “Virginia Woolf” starring Irene Worth, Frances Conroy and Tony Musante in 1963. Perhaps in that selfish and greedy decade audiences weren’t ready for Albee’s bitingly witty depiction of suburban American life and how it ends.

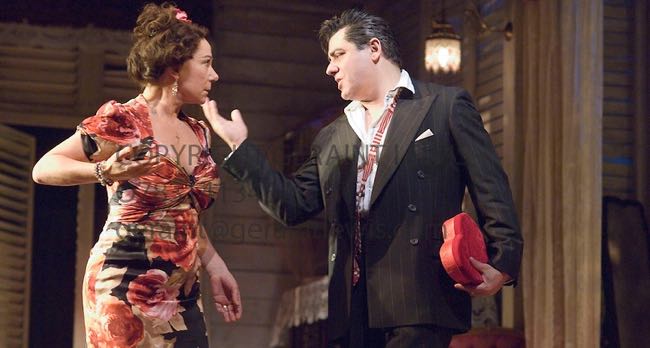

The setting is a comfortably bland middle class home in Connecticut where young and beautiful Jo (Catherine McCormack) is in great pain caused by terminal cancer. She deals with it by ingesting large quantities of drugs and whisky and being difficult with her husband, Sam (Robert Sella), and is caustic with their friends.

Timid Edgar (Chris Larkin), his bossy wife Lucinda (Vivienne Benesch) and rednecked Fred (Glenn Fleshler) and his spirited girlfriend Carol (Jennifer Regan) have joined Sam and Jo for an evening of drinking and party games designed so that no one need address the issue of Jo dying.

Racked with pain, Jo alternately clutches and spurns the devoted Sam and excoriates their four guests who don’t know whether to join in the sparring or accept her insults meekly. The party has erupted into a shouting match and then wound down with the guests departed, but not far away, when the title character shows up with a mysterious companion just before the first-act curtain comes down.

“Yes,” she says, “we’ve come to the right place.”

She shows up, all business but with no little sympathy, claiming to be Jo’s mother, Elizabeth, but Jo is upstairs asleep and Sam is hung-over and disbelieving. Elizabeth fits no description he’s ever heard of Jo’s mother, and her companion, a glib and debonair black man named Oscar (Peter Francis James) is like no one he’s ever met.

The friends return to make amends for the ugly evening, but Sam instinctively sees what Elizabeth represents and denies it angrily. He recoils in horror even as Jo reaches out for the final embrace.

It’s far from being as grim as it sounds although Albee is not gentle in his portrait of adult lives wasted on empty passions and meaningless pursuits. The characters are stereotypes and perhaps the playwright doesn’t delineate them as assuredly as in his other plays, but still they are easily recognizable.

The mostly American cast acquit themselves well although Sella (Broadway’s “Stuff Happens”) hasn’t quite mastered the difficult challenge of his breakdown on stage. James is adroit as the mysterious stranger and McCormack’s portrayal of desperate pain and longing is both funny and deeply moving.

Smith is the joy you might expect her to be with faultless timing and delivery, and a satisfactorily faint American accent. Albee has his characters address the audience now and then and while at first jarring, it’s clear he means it to prevent a shroud of morbidity. It’s a purely theatrical device but under Anthony Page’s clear-eyed direction it works very well, and Smith shows how it’s done by the very best.

Theatre Royal Haymarket, London (March through June 7, 2007); Presented by Robert Fox, Elizabeth I. McCann and the Shubert Organisation; Credits: Playwright: Edward Albee; Director: Anthony Page; Set designer: Hildegard Bechtler; Costume designer: Amy Roberts; Lighting designer: Howard Harrison. Cast: Elizabeth: Maggie Smith; Lucinda: Vivienne Benesch; Fred: Glenn Fleshler; Oscar: Peter Francis James; Edgar: Chris Larkin; Jo: Catherine McCormack; Carol: Jennifer Regan; Sam: Robert Sella.

‘Amazing Grace’ endures while slavery continues

By Ray Bennett

Michael Apted’s “Amazing Grace,” which tells how the British Empire put an end to the slave trade that had helped it dominate the world, has grossed nearly $18.25 million in its first 38 days of U.S. theatrical release.

Not in blockbuster ranks, obviously, but considerably better than many recent Oscar-nominated and critically praised British films such as “Venus” ($3.3 million in 102 days), “Notes on a Scandal” ($17.4 million in 98 days), “The Last King of Scotland” ($17.3 million in 187 days), “Miss Potter” ($1.9 million in 94 days).

Pretty good, in fact, for a picture about bewigged men arguing politics and commerce in the halls of British parliament in the early 19th century. It still has to roll out around the world and may expect a long life on DVD.

Ioan Gruffudd (above, with Ramola Garai, as his wife) plays William Wilberforce, who was the leading spokesman against the slave trade to the American colonies in parliament, and the film features an array of top British actors as key figures of the time, including Albert Finney as John Newton, the reformed slave ship captain who wrote the enduring hymn “Amazing Grace.”

in parliament, and the film features an array of top British actors as key figures of the time, including Albert Finney as John Newton, the reformed slave ship captain who wrote the enduring hymn “Amazing Grace.”

Benedict Cumberpatch plays the young Prime Minister William Pitt, Michael Gambon is the wily Lord Charles Fox and Ciaran Hinds is the vile Lord Tarleton. Youssou N’Dour is Oloudaqh Equiano, the dignified former slave who survived to write about his ordeal, and Rufus Sewell is Thomas Clarkson (left), a rebellious and relentless campaigner who is a much-overlooked hero of the time.

Many critics praised the picture although some suggested it is too earnest and therefore dull. I didn’t review it but I think Apted did a terrific job to render onscreen an important and difficult episode in history. He takes the drama out of the dusty corridors of power and draws terrific performances from his cast, especially Gruffudd and Sewell. Kenneth Turan wrote in the Los Angeles Times:

Adam Hochschild’s excellent book “Bury The Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves” covers many of the events in the film and the author says: “Wilberforce has always been more politically convenient to lionise as the hero. He was such a respectable figure of the establishment, while Clarkson was quite a radical and quite a rabble-rouser, especially in his younger days. To me, he is by far the more interesting figure: riding 35,000 miles by horseback all over England, and going out again in his 40s and his 60s and making the rounds. An incredible man. He really got shortchanged by history.”

author says: “Wilberforce has always been more politically convenient to lionise as the hero. He was such a respectable figure of the establishment, while Clarkson was quite a radical and quite a rabble-rouser, especially in his younger days. To me, he is by far the more interesting figure: riding 35,000 miles by horseback all over England, and going out again in his 40s and his 60s and making the rounds. An incredible man. He really got shortchanged by history.”

“Amazing Grace” leaves plenty still to be said on the topic as the issue of African slavery remains in the headlines to this day, not to mention all the other forms of slavery extant in the world. The Slave Trade Act was enacted on March 25, 1807, prohibiting British ships from transporting slaves, although Britain did not abolish slavery in its territories until 1833.

There was a ceremonial service to mark the occasion at Westminster Abbey (where Wilberforce is buried) attended by Queen Elizabeth II and British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who called the slave trade “one of the most shameful enterprises in history.” Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan William gave a sermon in which he said that slavery remained “hideously persistent” around the world, though in different forms than 200 years ago.

He said: “Whether in the forms that Wilberforce and Clarkson and Equiano denounced or in the forms in which it is still around today, debt slavery and sex-trafficking and forced labour and child abduction and exploitation, it is an offence against the created order of equality, an offence against the dignity of humans …

“We are born into a world already scarred by the internationalising and industrialising of slavery in the early modern period, and our human inheritance is shadowed by it. We who are the heirs of the slave-owning and slave-trading nations of the past have to face the fact that our historic prosperity was built in large part on this atrocity; those who are the heirs of the communities ravaged by the slave trade know very well that much of their present suffering and struggling is the result of centuries of abuse …

“Slavery is not a regional problem in the human world; it is hideously persistent in our nations and cultures. But today it is for us to face our history; the Atlantic trade was our contribution to this universal sinfulness.”