By Ray Bennett

The incomparable Maureen Stapleton, who died in 2006, played Serafina delle Rosa, the red hot Sicilian mama in Tennessee Williams’ “The Rose Tattoo” when it opened on Broadway in 1951. Stapleton and co-star Eli Wallach won Tony awards as did the play, which ran under Daniel Mann’s direction at the Martin Beck Theatre for 306 performances.

Stapleton (left) won her second Tony Award 20 years later in Neil Simon’s “The Gingerbread Lady,” having picked up an Emmy for “Among the Paths of Eden” in 1968. She won an Academy Award for her wonderful performance as Emma Goldman in Warren Beatty’s Oscar-winning epic “Reds” in 1981.

Chicago-born actor/director Sam Wanamaker, who was blacklisted in the McCarthy era and was based in the U.K. for most of his life, first took “The Rose Tattoo” to London in 1959, where he directed and starred as the lusty truck driver who falls for Serafina, played by Lea Padovani.

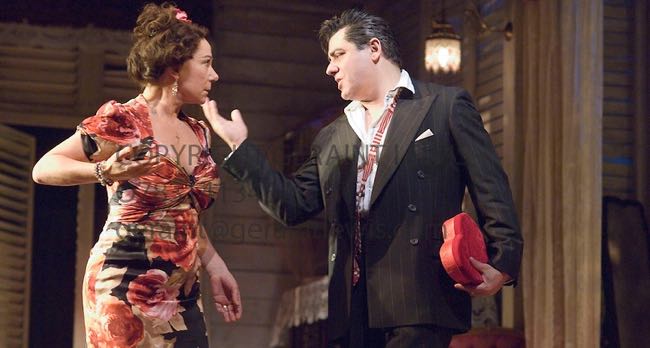

Now Sam’s daughter Zoe Wanamaker has taken the leading role in a new production at the National Theatre but, sad to say, it was not a great idea. Here’s how my review begins in The Hollywood Reporter:

LONDON — As Madame Hooch in “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone”, Zoe Wanamaker teaches flying and is the referee at Quidditch games. In the National Theatre revival of Tennessee Williams’ “The Rose Tattoo”, she plays a morbidly emotional hothouse flower named Serafina delle Rose, but it would take more than broomsticks to make this overblown production fly.

Williams wrote the play in 1951 for flamboyant Italian actress Anna Magnani, and while she never took the role onstage, her over-the-top wailing in the 1955 movie was enough to win her an Oscar in the same year that Ernest Borgnine won for “Marty.”

Although it is set in the U.S. Gold Coast somewhere between Mobile and New Orleans, “Tattoo” lacks Williams’s usual rich Southern atmosphere because its characters are all Italian. The action could just as well take place somewhere in the playwright’s feverishly imagined idea of Italy.

Serafina is a voluptuous seamstress with volcanic emotions whose adored truck driver husband is killed, plunging her into a three-year exercise in ornate grief. She never puts on more than a slip; she argues with her pretty teenage daughter, rages at the local women and fights with the village priest.

FILM REVIEW: ‘The Lives of Others’

By Ray Bennett

The McGuffin in Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s vastly overrated film about state repression, “The Lives of Others,” which opens in the U.K. on April 13, is a manual typewriter with a red ribbon. Just the thing you would choose if you were writing subversive reports about a cruel regime that bugs your home, films your every move and compromises the ones you love in order to trap you.

The machine is hidden beneath the floorboards in the apartment of a playwright named Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) in East Berlin before the Wall came down. He uses it secretly to write reports about the evils of the obtuse but relentless state police, the Stasi, which are smuggled to the West for publication. The existence of the typewriter becomes the focus of an intense investigation by the Stasi that leads to betrayal, ruin and death.

The whole tension of the film comes to rest on the typewriter but it beggars belief as the screenplay establishes that the playwright famously writes in longhand and has someone transcribe his plays. As the entire weight of a corrupt and insidious political apparatus bears down on Dreyman, his unfortunate lover and his friends, you wonder if he wishes he’d just used his pen.

That’s not the only problem with the film, however. Perhaps the ugliness of East German repression is news to the folks who lived there, and airing it is a good thing. But it’s nothing new for those of us in the West who have been reading historians and novelists such as Len Deighton and John Gardner on the subject for decades.

Director and screenwriter Von Donnersmarck’s film is well acted, especially by Koch, Ulrich Muehe (pictured), as the most obsessive Stasi operative, and Martina Gedeck as Dreyman’s lover. But it has the dull grey look of a poor TV movie and what tension there is dissipates as chapters are tacked on at the end. The story’s resolution reflects sensitivity to viewers wishing to be comforted in their living rooms. It suffers from a wish to offer healing. The film cowers in the end instead of raging.

I’m in the minority on this as most critics raved about “The Lives of Others” and it picked up several prizes including the Academy Award for best foreign-language film. I find that baffling when the direct Oscar competition included cinematic treasures such as “Pan’s Labyrinth” and “Days of Glory,” not to mention those without nominations including “Volver,” “Letters from Iwo Jima” and “Apocalypto.”