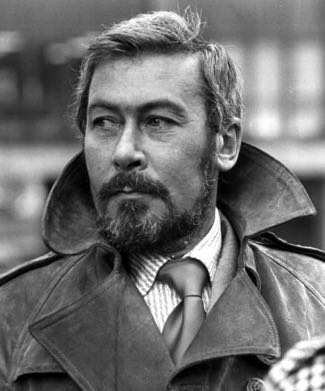

Ivan Barnev in Jiri Menzel’s ‘I Served The King Of England’

By Ray Bennett

BERLIN – Forty years after their “Closely Watched Trains” won the Oscar for best foreign-language film, director Jiri Menzel has adapted another novel by the late Bohumil Hrabal, and history could well repeat itself when Academy members get to see “I Served the King of England,” which screened here in competition.

The new picture has a similar sensibility. It’s a picaresque tale of an ambitious but naive Czechoslovakian waiter whose gumption, opportunism and blinkered awareness of events see him thrive amid political and social upheaval. It is a saga told sumptuously of childlike wonder in the face of darkest corruption and war, mixing high comedy, surreal sequences and genuine drama viewed from a wise, jaundiced perspective.

Given time to finds its audience, which is anyone who likes the Coen brothers, “Served” could do well across all territories as its visual humor and topical significance give it mainstream grown-up appeal.

The film begins with a grizzled, aging Jan Dite (Oldrich Kaiser) being released after 15 years in a Czech prison and assigned to a job as a roadman near the German border. He’s given a wrecked building to live in, and as he works cheerfully to rebuild it, flashbacks tell how the fates have conspired to bring him to this pretty pass.

As a young man, Jan (Ivan Barnev) is short, observant and quick-witted, selling frankfurters to passengers on briefly stopped trains. In the first comic sequence — which is shot like a silent film and will be echoed throughout “Serve” — he hangs on to a large amount of change until the train pulls out, taking the buyer with it. His innate innocence surfaces too late, and he chases the train with arm outstretched to return the cash, but to no avail.

The film switches back and forth from Jan’s adventures as a young man to his later life, where his remote existence is brightened by the appearance of a lethargic but attractive young woman, Marcela (Zuzana Fialova), accompanied by a professor (Milan Lasica) seeking wood to make violins and cellos.

Young Jan makes his way from one waiting job to a better one, and these hotel and restaurant scenes are wonderfully contrived with visual comedy matched by undercurrents of shrewd political comment. In one of the cleverest, the film’s title is explained. Hrabal and Menzel employ satire with the sharpest scalpel exercised within comic episodes of high wit and slapstick.

Jan’s young life is full of delectably willing young women, though they are usually at the beck and call of salacious capitalists. When he falls in love, it’s with a young German woman, Liza (Julia Jentsch), who believes in all things Aryan and supports the Nazi invasion.

The story then follows their passage through World War II and later the Soviet communist occupation and how Jan gets everything he wishes for and then loses it all. Barnev is sublime as the young man, gifted with the physical grace of great comedians and with expressive features that encourage sympathy despite some of the unsympathetic things he does. Kaiser is equally good as the wiser, sadder older man.

The acting throughout is of the highest order, and other standout credits include the colorful production design by Milan Bycek and Ales Brezina’s jaunty piano score.

Cast: Ivan Barnev, Oldrich Kaiser, Julia Jentsch, Martin Huba, Marian Labuda, Milan Lasica, Josef Abrham, Jiri Labus; Director-screenwriter: Jiri Menzel; Based on the novel by: Bohumil Hrabal; Producers: Robert Schaffer, Andrea Metcalfe; Director of photgraphy: Jaromir Sofr; Editor: Jiri Brozek; Production designer: Milan Bycek; Music: Ales Brezina; Costume designer: Milan Corba.

This review appeared in The Hollywood Reporter and Reuters

One winner among the Oscar awards montages

By Ray Bennett

No surprise that the best film montage in last night’s Oscar show was Giuseppe Tornatore’s impressionistic assembly of clips from the Academy’s best foreign-language film winners.

Directors Nancy Meyers (“The Holiday”) and Michael Mann (“Miami Vice”) didn’t bother with such detail and their montages suffered for it. Meyers put together a jaunty look at writers portrayed in movies and while the clips mostly featured typewriters and frustration, it was harmless fun.

Mann’s look at America through its movies was a shotgun affair with nods to many things from immigrants to gangsters to racism to big business, but it ended strangely with lingering scenes of U.S. sacrifices in war followed by James Brown singing “I Feel Good.”

The montage accompanying the tribute to composer Ennio Morricone was a dull collection of snippets of scenes from various films he’s scored with a few bars from his scores. It was not enough to convey the immense sweep and delicate subtlety Morricone brings to his music (e.g. “The Legend of 1900”).

Jodie Foster introduced with considerable grace the annual salute to filmmakers who died in the past year. Such as Glenn Ford, Darren McGavin, Maureen Stapleton, Peter Boyle, Sidney Sheldon, Jack Palance, and Jack Warden left a trove of memories.

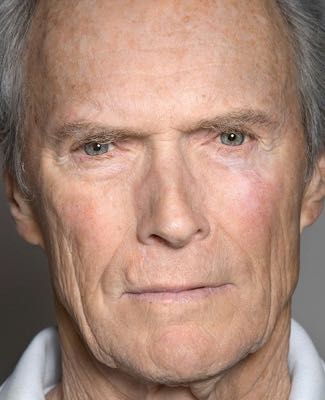

Full marks to whoever assembled the salute for having the wit to end on a shot of the late American master Robert Altman (above) viewing the proceedings with an expression typically wry and skeptical.