By Ray Bennett

With most movie stars it’s not very difficult to sort out a Top 10 of your favourite films but Gene Hackman’s exceptional 40-year career has included so many terrific performances in such a wide range of films that it’s impossible. As the retired actor turns 95 today, here’s an extended list of Hackman films from his 99 acting credits that are even more watchable than most.

Obviously there are his Oscar-winning appearances in “The French Connection” (1971) and “Unforgiven” (1992) and his nominated roles in “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967), “I Never Sang for My Father” (1970) and “Mississippi Burning” (1989) plus the sequel “The French Connection II” (1975) and pleasing turns in “Superman” (1978) and “Superman II” (1980). But there are so very many more.

I met him once at the Long Beach Grand Prix in 1980 when he was the celebrity winner of the Toyota Pro/Celebrity Race with Parnelli Jones the pro winner. Not known for his patience with reporters, I approached him gingerly as he stood quietly by himself but he turned out to be completely relaxed and happy to chat.

Hackman retired in 2004 after “Welcome to Mooseport” and director Alexander Payne said at a Bafta Q&A last year that he had declined repeated attempts to get him to play what became Bruce Dern’s Oscar-nominated role in “Nebraska”.

It was a great disappointment when he retired but a great pleasure to learn from William Friedkin, who directed the actor in the “French Connection” films, at dinner at the Locarno International Film Festival a few years back, that Hackman was hale and hearty and enjoyed his family and his painting in his retirement home in Santa Fe.

Here’s my list of 20 other must-see Gene Hackman films.

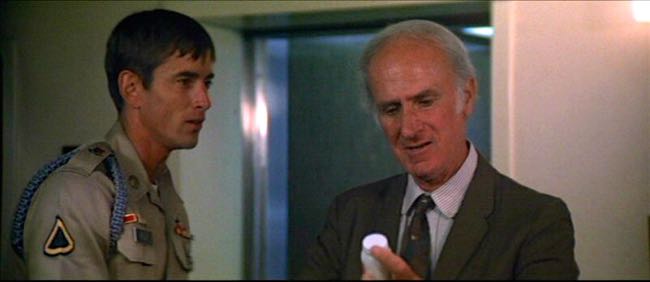

Scarecrow (above, 1973)

My favourite Gene Hackman movie in which he displays his extraordinary ability to be dangerous, sympathetic, vulnerable, and remarkably funny. He plays an ex-convict on his way back east where he aims to open a laundromat but his plans are diverted when he encounters a forlorn ex-sailor (Al Pacino) on the highway and decides to help him find his former sweetheart and their child. Directed by Jerry Schatzberg (“The Panic in Needle Park”), it co-stars Dorothy Tristan, Ann Wedgeworth and Eileen Brennan. Hackman’s striptease in a bar is a joy to see.

The Royal Tenenbaums (above, 2001)

Splendidly enjoyable Wes Anderson saga about the weird and wonderful Tenenbaum family whose estranged patriarch (Hackman) returns to announce that he is soon to die. Anjelica Huston plays his former spouse with Ben Stiller, Gwyneth Paltrow and Luke Wilson as their offspring. The cast includes Owen Wilson, Bill Murray, Danny Glover, Seymour Cassel, Kumar Pallana and Alec Baldwin. Hackman is marvellous and the entire cast raise their game delightfully.

The Conversation (1974)

Superb and highly praised study of a surveillance expert who comes to suspect that the subjects of one of his assignments will become murder victims. Paced deliberately by writer/director Francis Ford Coppola as the tension mounts, it shows Hackman at his quiet and observant best. John Cazale, Allen Garfield, Federic Forrest and Cindy Williams co-star.

Under Fire (above, 1983)

One of the best films about dirty dealings by the United States in Central America directed by Roger Spottiswoode. Hackman, Joanna Cassidy and Nick Nolte play journalists covering the final days of the corrupt reign of dictator Somoza in Nicaragua in the 1970s. Ed Harris co-stars.

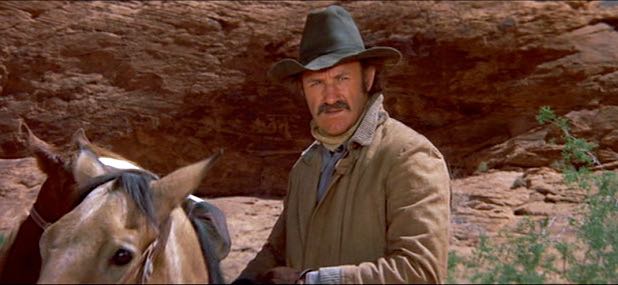

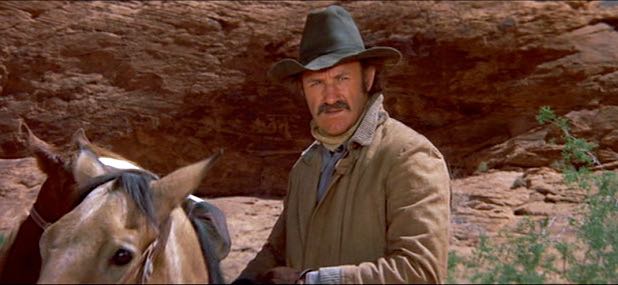

Bite the Bullet (above, 1975)

Richard Brooks writes and directs an epic and hugely entertaining western about a grand horserace across plains and deserts with Hackman as an ex-Rough Rider and a fine cast that includes Candice Bergen, James Coburn, Ben Johnson, Ian Bannen, Jan-Michael Vincent and Dabney Coleman.

Hoosiers (1986)

Hackman plays a basketball coach tarnished by scandal who goes to work at a small town highschool and inspires the team to go for the championships despite local whispers and naysaying. Directed by former “Hill Street Blues” producer David Anspaugh, it’s a gentle and emotional film that co-stars Oscar nominated Dennis Hopper with Barbara Hershey and Sheb Wooley. Jerry Goldsmith also had an Oscar nomination for his evocative score.

Cisco Pike (1972)

Sex, drugs and rock’n’roll set in Venice, CA, with Kris Kristofferson as a faded star whose attempt to go straight after a jail term for dealing drugs is threatened by a crooked cop (Hackman) who blackmails him into another drug deal. Karen Black, Harry Dean Stanton, Roscoe Lee Browne co-star with Viva and Joy Bang.

Prime Cut (above, 1972)

Gritty crime story about a tough Chicago hoodlum (Lee Marvin) who is sent to a cattle ranch in Kansas City run by a flamboyant criminal who uses his mincing machine to deal with miscreants and trades in women (including Sissy Spacek in her debut) that he keeps in his cattle pens. Seedy, sordid and hugely entertaining

Heist (2001)

Tense and inventive story with Hackman as a veteran jewel thief mixed up in a job with people he has no reason to trust. Written and directed by David Mamet, it co-stars Danny DeVito, Delroy Lindo, Sam Rockwell, Ricky Jay and Patti LuPone.

Marooned (1969)

Hackman is one of three US astronauts stranded in space in an exciting John Sturges picture that also stars Gregory Peck, Richard Crenna, David Janssen, James Franciscus, Lee Grant and Mariette Hartley. It won the Oscar for best effects that year.

Downhill Racer (1969)

Engaging sports yarn directed by Michael Ritchie about a US ski team led by Robert Redford, who won the Bafta for best actor, with Hackman as the coach.

The Gypsy Moths (1969)

John Frankenheimer’s film of James Drought’s 1955 novel about a July 4 weekend show in a small American town put on by a team of barnstoming skydivers. Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr are reunited 16 years after “From Here to Eternity” and the strong cast includes Bonnie Bedelia, Shree North and Scott Wilson.

Twilight (1998)

Hackman, Paul Newman and James Garner star in an elegant and elegiac tale about oldtimers mixed up in a 20-year old murder case directed by Robert Benton, who scripted with Richard Russo. Susan Sarandon co-stars along with Reese Witherspoon, Stockard Channing, Giancarlo Esposito, Liev Schreiber, Margo Martindale and M. Emmet Walsh.

The Firm (1993)

David Rabe, Robert Towne and David Rayfiel make cracking improvements to John Grisham’s thriller about a corrupt Memphis law firm and Sydney Pollack keeps a furious pace. Hackman plays a weak and vulnerable crooked lawyer as newcomer Tom Cruise and his wife Jeane Tripplehorn attempt to bring justice to bear along with David Strathairn and Oscar-nominated Holly Hunter. Hal Holbrook and Wilford Brimley are among the bad guys with Ed Harris as a determined lawman. Terrific Oscar-nominated piano score by Dave Grusin.

Crimson Tide (above, 1995)

Tony Scott directs a version of “Mutiny on the Bounty” underwater in a sturdy and suspenseful drama that pits an old-school taskmaster submarine captain (Hackman) against a formidable younger officer (Denzel Washington) who fears that his boss has lost his judgment. Matt Craven George Dzundza, Viggo Mortensen and James Gandolfini co-star.

Get Shorty (1995)

Savvy Elmore Leonard yarn directed wittily by Barry Sonnefeld about an East-coast hoodlum (John Travolta) who is beguiled by the easy takings on hand in greedy and gullible Hollywood. Hackman plays a not-very-bright producer and the cast includes Danny DeVito, Rene Russo and Dennis Farina. Terrific soundtrack with score by John Lurie.

No Way Out (1987)

Hackman’s on the dark side as a weak politician in Roger Donaldson’s tense little thriller in which a navy officer (Kevin Costner) must beat the clock in the hunt for the real villain after the politico’s mistress is killed. Sean Young co-stars with George Dzundza, Howard Duff and Will Patton in a gripping turn as the politician’s devious but increasingly desperate aide.

The Package (1989)

Andrew Davis, who went on to make “Under Siege” and “The Fugitive”, directs a snappy little thriller in which Hackman plays a veteran Green Beret sergeant whose Airborne Ranger prisoner (Tommy Lee Jones) escapes as he escorts him back to the US. Joanna Cassidy, John Heard, Dannis Franz and Pam Grier co-star.

Full Moon in Blue Water (1988)

A sweet and moving story with Hackman as a widower named Floyd who owns a bar in a small Texas town on the Gulf of Mexico and struggles with a failing business, depression from his grief, and an aging father-in-law (Burgess Meredith) who suffers from dementia. Teri Garr and Elias Koteas play sympathetic workers at the bar with Kevin Cooney as a businesman who aims to take advantage of Floyd’s dilemma.

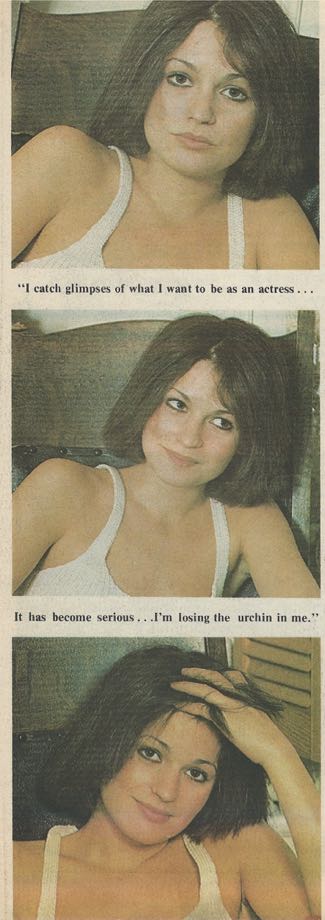

Night Moves (1975)

Hackman plays a former football player turned private detective who is hired to find the wayward teenaged daughter of a faded Hollywood starlet. Directed by Arthur Penn, it co-stars Jennifer Warren, Susan Clark, Edward Binns, Harris Yulin and Kenneth Mars with a provocative debut by the then 18-year-old Melanie Griffith.

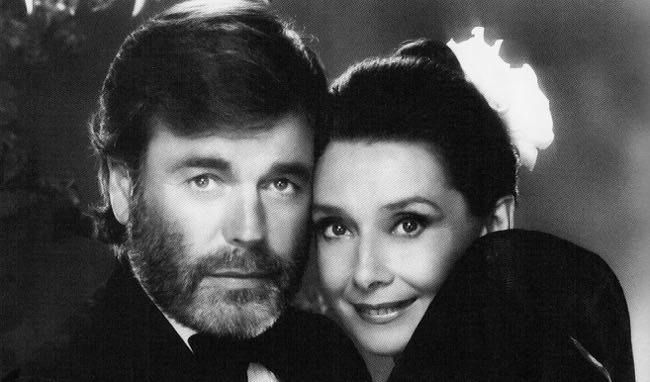

The Canadian writer was nominated for an Oscar for his screenplay of the 1978 movie version of “Same Time, Next Year”, which was directed by Robert Mulligan and starred Alan Alda and Ellen Burstyn (pictured below), who had won a Tony Award for the stage version and was nominated for an Osca as best actress for the movie.

The Canadian writer was nominated for an Oscar for his screenplay of the 1978 movie version of “Same Time, Next Year”, which was directed by Robert Mulligan and starred Alan Alda and Ellen Burstyn (pictured below), who had won a Tony Award for the stage version and was nominated for an Osca as best actress for the movie.

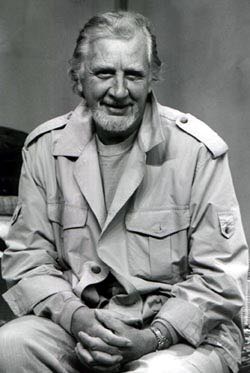

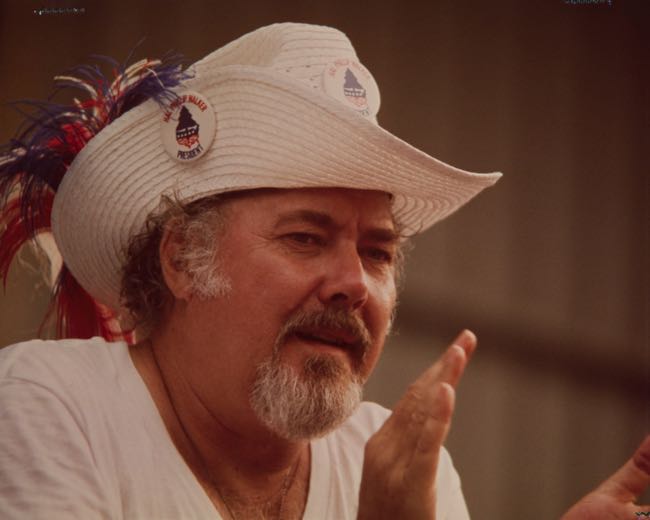

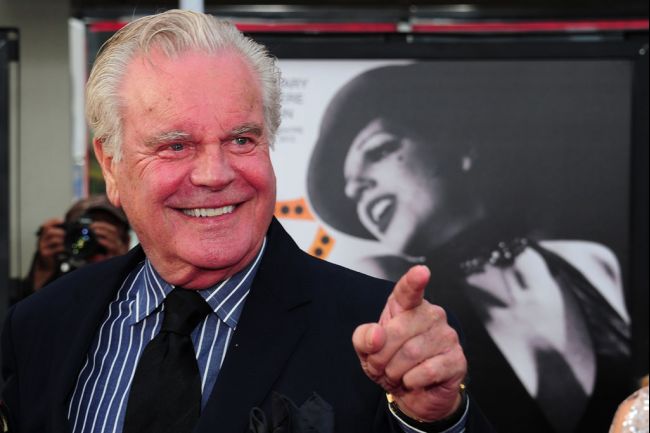

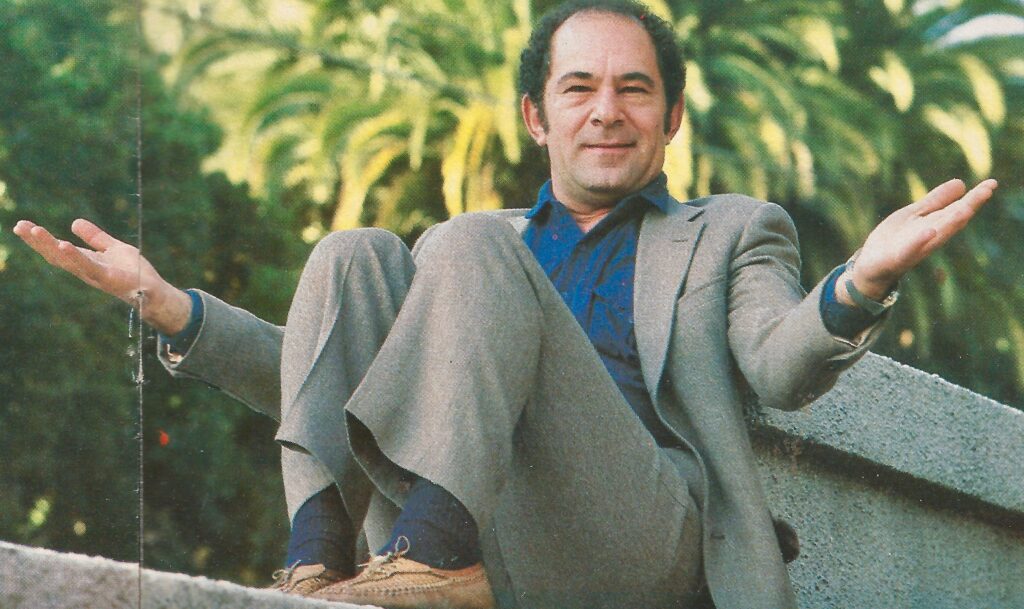

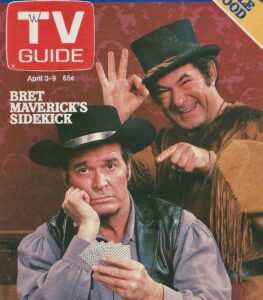

‘That’s how I like to think of myself,’ Margolin told me in 1982 for a cover story in Canadian TVGuide. ‘Some guys can take a sidekick, others can’t. Jim didn’t have a sidekick for many years and he doesn’t need one but somehow this has evolved snd I think we work well together.’

‘That’s how I like to think of myself,’ Margolin told me in 1982 for a cover story in Canadian TVGuide. ‘Some guys can take a sidekick, others can’t. Jim didn’t have a sidekick for many years and he doesn’t need one but somehow this has evolved snd I think we work well together.’ Taking voice lessons to lose his Texas accent, Margolin gradually won small stage roles leading to the road company that took him to Los Angeles in 1960. There, he dound steady work on TV series such as ‘My World and Welcome to It’ and ‘The Partridge Family’ and acting in movies including ‘Death Wish’ and ‘Kelly’s Heroes’.

Taking voice lessons to lose his Texas accent, Margolin gradually won small stage roles leading to the road company that took him to Los Angeles in 1960. There, he dound steady work on TV series such as ‘My World and Welcome to It’ and ‘The Partridge Family’ and acting in movies including ‘Death Wish’ and ‘Kelly’s Heroes’. Margolin’s sidekick eccentricity found its purest expression in Garner’s reprise of his western show, ‘Breat Maverick’. He played Philo Sandeen, a Yugoslavian who came to the New World, decided that he preferred to live the way the Indians lived and preferred to go by the name Great Scout Standing Bear. Philo Sandeen was much more capable than Angel and more dangerous. Margolin said, ‘After a while, as Angel, it became incumbent to get a laugh on everything I did and I didn’t want to fall into that.’

Margolin’s sidekick eccentricity found its purest expression in Garner’s reprise of his western show, ‘Breat Maverick’. He played Philo Sandeen, a Yugoslavian who came to the New World, decided that he preferred to live the way the Indians lived and preferred to go by the name Great Scout Standing Bear. Philo Sandeen was much more capable than Angel and more dangerous. Margolin said, ‘After a while, as Angel, it became incumbent to get a laugh on everything I did and I didn’t want to fall into that.’

20 David Niven movies you should see

By Ray Bennett

David Niven, who was born 115 years ago today and died aged 73 in 1983, gave Ron Base and me the best quote of all time.

The Oscar-winning British actor was on a book tour to promote his first memoir, the brilliant “The Moon’s a Balloon”, in 1972. Ron and I, who worked at The Windsor Star across the river, went to a Detroit hotel ballroom for a lunch – a hospital fundraiser – at which Niven was to speak. We were told we could interview him afterwards.

Lunch was great because we sat at a table with actress Constance Towers so we encouraged her to share yarns of her films with John Ford. Niven was a masterful raconteur and he spun hilarious tales from his book.

Always one of my favourite screen actors, Niven was the definition of suave and debonair from his start in comedies such as “Thank You, Jeeves” (1936), in which he naturally played Bertie Wooster (pictured above with Virginia Field and Arthur Treacher as Jeeves), and war pictures such as “Dawn Patrol” (1938).

He might be best known for his role as Phileas Fogg in “Around the World in Eighty Days”, which won five Academy Awards in 1957 including Best Picture. He is perfect and Shirley MacLaine and Robert Newton (pictured below) have their moments although the film is a bloated travelogue stuffed with odd star cameos.

Here are 20 other David Niven movies worth watching:

“The Sea Wolves” (1980) Great fun based on a true story as Gregory Peck, Niven and Roger Moore play former soldiers who are sent on a secret mission in World War II to destroy a Nazi ship based in neutral Goa. Andrew V. McLaglen directs Reginald Rose’s entertaining script with a cast that includes Trevor Howard and Patrick Macnee.

“Murder by Death” (1976) Neil Simon’s Agatha Christie spoof has some wonderful moments from a cast in which Niven is joined by Eileen Brennan, Truman Capote, James Coco, Peter Falk, Alec Guinness, Peter Sellers and Maggie Smith.

“The Extraordinary Seaman” (1969) Bizarre comedy that I’ve always been fond of with Niven as the ghost of a drowned World War I sea captain who fetches up with his boat in World War II, helps some American sailors survive and falls for an American woman in the Phillipines. John Frankenheimer (“The Manchurian Candidate”) directs Faye Dunaway, Alan Alda, Mickey Rooney and Jack Carter.

“Lady L” (1965) Ambitious if flawed comedy directed by Peter Ustinov, who adapated a novel by Romain Gary about an ageing woman played by Sophia Loren who recalls the loves of her life. Niven, Paul Newman, Cecil Parker and Philippe Noiret are among them.

“The Bedtime Story” (1964) Comedy Marlon Brando and Niven as conmen who challenge each other to seduce women on the Côte d’Azur such as an heiress played by Shirley Jones. Bosley Crowther in the New York Times said the two actors hit “a comedy peak” and “it is a very funny picture. It was remade in 1988 as “Dirty Rotten Scoundrels” with Steve Martin, Michael Caine and Glenne Headley, and later became a successful stage play.

“The Pink Panther” (1963) Niven and Robert Wagner are the jewel thieves in pursuit of the fabulous gem worn by Claudia Cardinale (pictured above) although Peter Sellers steals every scene as Inspector Clouseau. Blake Edwards directs the first of the “Pink Panther” series, which he co-wrote with Maurice Richlin (“Operation Petticoat”, “Pillow Talk”). Henry Mancini, of course, wrote the infectious score.

“55 Days at Peking” (1963) Nicholas Ray epic about American soldiers and British diplomats in the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900. Niven stars with Charlton Heston, Ava Gardner and a very large cast with cinematography by the great Jack Hildyard (Oscar-winner for “The Bridge on the River Kwai”) and music by Dimitri Tiomkin (Oscar-winner for “High Noon”, “The High and the Mighty” and “The Old Man and the Sea”).

“The Best of Enemies” (1961) Smart and cynical comedy about a square-off in the Abyssinian desert in World War II between an Italian captain (Alberto Sordi) and a British major (Niven). Directed by Guy Hamilton (“Goldfinger”, “Funeral in Berlin”), it co-stars Michael Wilding and Harry Andrews atop a raft of British and Italian character actors.

“The Guns of Navarone” (pictured above, 1961) Grand wartime adventure directed by J. Lee Thompson and based on a novel by Alistair MacLean about a group of Allied soldiers who must destroy a giant Nazi cannon so that convoys at sea might remain safe. Niven stars with Gregory Peck, Stanley Baker, Anthony Quayle, James Darren, Irene Papas, Gia Scala, Richard Harris and Anthony Quinn, whom Peck told me was the greatest scene-stealer in the movies.

“Ask Any Girl” (1959) Frothy comedy about brothers who fall for the same woman although one doesn’t realise it. Shirley MacLaine stars with Niven and Gig Young (“They Shoot Horses, Don’t They”) with the late Rod Taylor also in the cast.

“Separate Tables” (1958) Niven was named best actor at the Academy Awards for his performance as a stiff British Army officer with a secret in Delbert Mann’s version of the Terence Rattigan play about a group of off-season residents of a middle-class hotel at the English seaside town of Bournemouth. Deborah Kerr (pictured above), Rita Hayworth, Burt Lancaster and Gladys Cooper co-star with Wendy Hiller, who won the Oscar for best supporting actress.

“Bonjour Tristesse” (1958) Saucy Otto Preminger story of an unconventional playboy (Niven) and his fetching daughter, played by Jean Seberg (pictured above). Deborah Kerr and Mylène Demongeot co-star in a film whose reputation has grown over the years.

“My Man Godfrey” (1957) Niven is a butler with a dubious past to an American family dominated by women played by such as June Allyson, Jessie Royce Landis, Eva Gabor and Martha Hyer. Henry Foster (“Harvey”) directs.

“The Way Ahead” (1944) Carol Reed (“The Third Man”) directs a morale-building drama written by Eric Ambler and Peter Ustinov about conscripts who learn about battle in North Africa. Niven stars with a raft of British character actors including Stanley Holloway (“My Fair Lady”), James Donald (“The Great Escape” and William Hartnell (the first Doctor Who).

“Spitfire” (1942) British actor Leslie Howard (“The Painted Desert”, “Gone With the Wind”) directs and stars as the airplane designer who created the famous machine flown by “the few” in the Battle of Britain in World War II. Niven, who left Hollywood to return to England for the war, co-stars with Rosamund John.

“Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife” (1938) Directed by Ernst Lubitsch from a screenplay by Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder adapted from a play by Alfred Savoir. Screwball comedy on the French Riviera with Claudette Colbert and Gary Cooper. Niven co-stars along with the incomparable Edward Everett Horton.

“Dodsworth” (1936) William Wyler’s screen version of the Sinclair Lewis novel about a US industrialist (Walter Huston) and his wife (Ruth Chatterton) who drift apart on a European holiday picked up six Oscar nominations. Niven co-stars along with Paul Lukas, Mary Astor and Maria Ouspenskaya.

“The Charge of the Light Brigade” (below, 1936) The famous tale directed by Michael Curtiz, who gave Niven the title of his second memoir along with other very funny English-language clangers, my favourite of which is when the exasperated director told Errol Flynn (who starred opposite Olivia de Havilland) and Niven: “You think I know fuck nothing, but I know fuck all!”