By Ray Bennett

CANNES – “The Edukators” is that rare beast, a terrific movie that boasts intelligent wit, expert storytelling, delightful characters, and grown-up dialogue plus suspense and a wicked surprise ending. Continue reading

By Ray Bennett

CANNES – “The Edukators” is that rare beast, a terrific movie that boasts intelligent wit, expert storytelling, delightful characters, and grown-up dialogue plus suspense and a wicked surprise ending. Continue reading

By Ray Bennett

LONDON – There are many things that need to be right in a production of “Cyrano de Bergerac” and among the most essential, right off, is Cyrano’s nose. If we don’t buy the poet’s prominent proboscis, we won’t buy his poetry or his panache.

Jose Ferrer had an Oscar-winning nose in the 1950 movie; Steve Martin’s was rapier-like to match his wit in the 1987 “Roxane”; and Gerard Depardieu’s was robustly Gallic in the 1990 “Cyrano.”

In the National Theatre’s new production, Stephen Rea has a rough and ready olfactory device reminiscent in its ruggedness of another Academy Award-winning snout, the strapped-on attachment worn by Lee Marvin as Kid Shelleen’s evil twin brother Strawn in “Cat Ballou.”

It’s a completely successful nose, however, that is emblematic of a street-smart and enthusiastically vulgar adaptation of Edmond Rostand’s play by Irish poet Derek Mahon. Under Howard Davies’s rudely vigorous direction, the setting becomes an incongruous but fascinating melding of County Down and Gascony.

The stage is dominated by a vast scaffold construction like an immense set of monkey bars on which the players prance and dance, tumble and fight. It becomes a fortress, a theatre, or a mansion. At times it appears to be a giant space station out of “Star Trek” and that’s fitting as the story does not appear fixed in time

Stephen Rea’s Cyrano is less of a stylish Gascon swashbuckler and elegant wit and more of a Northern Irish roughneck who’s handy with cutting blade and quick tongue. Rea’s world-weary demeanor and hangdog expression work well with Mahon’s obscenity-laced verse and his romantic odes to the lovely Roxane (Claire Price, pictured with Rea) are laced with pessimism.

Cyrano is an obstinate man. “I like to be difficult; hostility keeps my backbone straight,” he says. He duels ruthlessly with any man who mentions his extreme features and keeps the Cadets de Gascogne well contained with his humor and willingness to brawl.

Roxane alone gets under his skin. “A star danced at her birth,” he says. But he believes she could never love him so when she falls for the inarticulate but handsome cadet Christian, Cyrano gladly spins the golden phrases that win her heart.

These, too, reflect a working-class sensibility and when Cyrano stands in for Christian in the famous balcony scene, calling up to her from the shadows below her window, Rea reveals the pain of the impersonation as much as the love within.

Director Davies employs the large space of the National’s Olivier stage for big musical numbers involving the cadets’ swordsmanship and later creates a spectacular battle sequence with great movement, lighting and crashing sound effects.

William Dudley’s inventive set also includes two walkways that reach out over the stalls so that characters emerge speaking from behind the audience. It both enlarges the action and allows for moments of great intimacy.

Aside from Cyrano, few characters stand out from the winning ensemble. Zubin Varla’s Christian appears mostly bewildered, both by Roxane’s apparent love for him and the threat of death. Malcolm Storry delivers the snap and arrogance of Count de Guiche, who also covets Roxane. Claire Price makes the object of everyone’s attention flighty and fractious at first but she grows to be quite moving in her understanding and acceptance of what fate hands her.

But it’s Rea and his feeling for words that make this “Cyrano” memorable. He speaks his lines as if making them up on the spot and while romantics may wish for a lighter, more debonair character, his wry and rueful countenance rings true.

Venue: National Theatre, runs through June 24; Cast: Cast: Stephen Rea, Claire Price, Zubin Varla; Malcolm Storry, Anthony O’Donnell, Nick Sampson, Katherine Manners; Playwright: Edmond Rostand, a new version by Derek Mahon; Director: Howard Davies; Set designer: William Dudley; Costume designer: John Bright; Music: Dominic Muldowney; Movement and dance: Christopher Bruce; Fight director: William Hobbs; Lighting designer: Paul Anderson; Sound designer: Paul Groothius; Company voice work: Patsy Rodenburg.

By Ray Bennett

LONDON – It’s a not so fine madness that has an unnamed present day Italian aristocrat believing for 20 years he is the medieval German King Henry IV in Luigi Pirandello’s steely fable, here in a new version by Tom Stoppard.

It was a fall from a horse while dressed as the Teutonic monarch during a pageant that brought on the delusion that has led to the loss of his lover, Matilda (Francesca Annis), to his rival Belcredi (David Yelland) and a life of pampered seclusion.

It is to his theatrically dressed home that a group including Matilda, Belcredi and a psycho-babbling shrink arrives intending to shock him out of his bewilderment. Since Himself, as his acolytes refer to the nobleman, is known to be fixated on a portrait of Matilda dressed as a medieval duchess, the notion is to surprise him with the very much alive Matilda along with her look-alike daughter Frida in period costume.

Pirandello’s great joke, embellished usefully by Stoppard, is that, once the conspirators are out of earshot, Himself bellows: “What a bunch of wankers!” In fact, he has been recovered from his madness for eight years but chooses to perpetuate the illusion of his delusion: “I decided to stay mad, to live as a madman of sound mind.”

Still, he allows the conspirators to act out their own pageant and the issue of masks and madness becomes profound leading to an act of violence that shatters any complacency on the matter.

Christopher Olam’s imposing set, spare but with tall columns; Adam Cork’s spirited music and sound score; and the mix of Olam’s period costumes and Armani modern dress, combine to put the senses successfully off kilter.

Francesca Annis, as the vain but anxious Matilda, and David Yelland, as her elegantly jealous lover Belcredi, smack of cocktails in St. Moritz and contrast nicely with the sackcloth-clad “madman”.

When Ian McDiarmid enters as “Henry IV,” he appears frail and lost, his voice plaintive but cunning and high like Maggie Thatcher’s. He simpers in his pretended insanity but bemoans his fate and keeps potential violence close to the surface. When he sheds his pretence, the emergence of a forceful and vengeful man is vivid and convincing.

Stoppard loves to entertain and he writes brilliantly for actors. McDiarmid takes his words and captivates entirely with his grasp of the subtleties between pretended madness and pretended sanity, and the treacherous gulfs between the two.

In director Michael Grandage’s firm hands, with ample use of the Donmar space, memories of the fancy-dress show where the fateful fall took place are seen from different viewpoints and life’s own rich and complex pageant is explored in the process. “The life we live as puppets,” sighs the king. What at first seems like a flight of fancy as a rich man indulges himself in games becomes a powerful examination of the way people masquerade as something other than their true selves while not always knowing who they really are.

Venue: Donmar Warehouse, runs through June 26; Cast: Ian McDiarmid, James Lance, Stuart Burt, Neil McDermott, Nitzan Sharron, Brian Poyser, Orlando Wells, David Yelland, Robert Demeger, Francesca Annis, Tania Emery; Playwright: Luigi Pirandello, a new version by Tom Stoppard; Director: Michael Grandage; Set & costume designer: Christopher Oram; Contemporary wardrobe: Giorgio Armani; Lighting designer: Neil Austin; Music & sound score: Adam Cork; Sound designer: Fergus O’Hare. Presented by the Donmar Theatre, supported by Stuart and Hilary Williams.

This review appeared in The Hollywood Reporter. Photo by Ivan Kyncl.

By Ray Bennett

LONDON – Elvis Presley was crowned the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll but few would argue that Little Richard did not have a more legitimate claim to the throne. The point is illustrated, more by accident than design, in the new British production, “Jailhouse Rock The Musical.”

The show is based loosely on the 1957 Presley movie. Loosely, in the sense that they’ve kept the plot but failed to secure rights to the Lieber and Stoller songs, including the hit title number. So the warden does throw a party at the county jail and the prison band is there but it doesn’t wail to quite the same effect.

Mario Kombou is Elvis as Vince Everett, the quick-tempered, curly-lipped, pelvis-swiveling hunk who is sent to the Big House for manslaughter and is there taken under the wing of an old-time country singer named Hawk Houghton (Roger Alborough). Hawk is a long-time con who is not the teeniest bit attracted to Vince,. Don’t even go there. He just wants to be his pal and teach him to play guitar. And collect 50% of his earnings when he’s released and becomes a big star.

That’s exactly what Vince becomes on the outside although it takes the love of a good, albeit rich, woman (Lisa Peace) and fights with cheating record label executives before he makes it. But what will happen when Hawk gets out and demands his cut, and will Vince remember his promise to help his good black jailbird buddy Quickly Robinson (Gilz Terera) obtain parole?

You might have thought that once the producers realized they weren’t going to get “Jailhouse Rock” and other great Presley songs from the film such as “Treat Me Nice”, “Don’t Leave Me Now” and “Young and Beautiful”, they might have gone back to the drawing board. Presley made 32 pictures in a 13-year Hollywood career and surely “Roustabout”, “Clambake” and “Harum Scarum” are fine titles to hang an Elvis stage musical on.

But they probably had the sets by then and double-decker jail cells form the backdrop throughout so that Vince’s connection to the downtrodden black inmates can be underscored with slide guitar and harmonica blues riffs and a little bit of gospel thrown in.

The result is a strange mishmash that devolves into a muddy-sounding rock concert as the plotlines are all resolved and it becomes an Elvis impersonator show without the fancy costumes. On the plus side, there are a couple of well-staged prison numbers involving “Stomp”-like percussion created by the chain gang chorus.

The only early Presley songs included are “Blue Suede Shoes”, “Good Rockin’ Tonight”, “A Fool Such as I” and “Are You Lonesome Tonight?”. Curiously, but pleasingly, two of the big showpieces are built around songs associated with country star Charlie Rich – “Lonely Weekends” and “Big Boss Man.”

A fine group of singers and musicians has been assembled to not only pound out the rock stuff but also perform unlikely but entertaining versions of left-field songs such as “Pretty Little Angel Eyes”, “Winter Wonderland” and “Big Rock Candy Mountain.”

Of course, it all comes down to the key performers. Roger Alborough is a far cry from the film’s indispensable Mickey Shaughnessy, looking a lot like Bill Haley without the kiss curl. Lisa Peace is given precious little to work with as Vince’s love interest. In the Presley role, Mario Kombou has all the charisma of Fabian although he can carry a delicate tune close to the Presley manner and grows in confidence once he’s belting out the big Elvis in Vegas numbers such as “Burnin’ Love” and “Suspicious Minds.”

The star of the show, however, is Giles Terera, who tops a series of crowd-pleasing cameos throughout with a genuine, show-stopping blast of Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti”. Long live the King!

Venue: Piccadilly Theatre, runs through Sept. 18; Cast: Mario Kombou, Roger Alborough, Lisa Peace, Giles Terera, Dominic Colchester, Melanie Marcus, Mark Roper, Annie Wensak, Gareth Williams; Writers: Rob Bettinson & Alan Janes; Director: Rob Bettinson; Producers: Alan Janes, Rene Sheridan; Co-producers: Jonathan Alver, Stephen Dee; Designer: Adrian Rees; Musical supervisor: Davi Mackay; Choreographer: Drew Anthony; Lighting designer: Alistair Grant; Sound designer: Simon Baker. Presented by Theatre Partners, the Jailhouse Company and Volcanic Island by arrangement with the Theatre Royal Plymouth.

This review appeared in The Hollywood Reporter.

By Ray Bennett

LONDON – Trevor Nunn’s breathtaking new production of “Hamlet” sees the Danish prince as James Dean in “East of Eden,” an immature and deeply torn young man whose love for his father and conflicted feelings for his mother drive him to extremes.

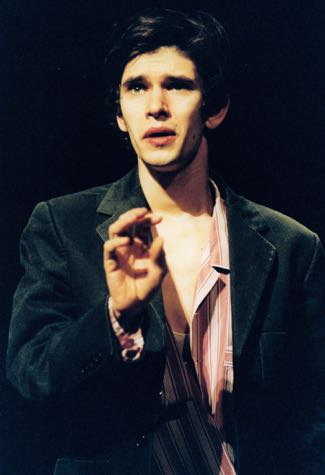

For his first staging of the play since 1970, Nunn has chosen a 23-year-old unknown named Ben Whishaw, who catapults instantly to fame with his unforgettable performance. As the young rebel with a cause, Whishaw actually looks more like the early Anthony Perkins, knife thin and gangly, his fear striking out from jangling neuroses and hormones, but who also possesses great calm with beseeching eyes and a killer smile.

As artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company and later director of the National Theatre, Nunn invigorated the Shakespeare canon and reinvented the musical with hits such as “Cats,” “Les Miserables,” “Oklahoma” and “Anything Goes.” His fresh take on “Hamlet,” with many of the youthful cast making their West End debuts, makes a luminous addition to those formidable accomplishments.

As artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company and later director of the National Theatre, Nunn invigorated the Shakespeare canon and reinvented the musical with hits such as “Cats,” “Les Miserables,” “Oklahoma” and “Anything Goes.” His fresh take on “Hamlet,” with many of the youthful cast making their West End debuts, makes a luminous addition to those formidable accomplishments.

When first the ghost of Hamlet’s late father is seen, Elsinore appears to be a vast and daunting place in an indeterminate age. John Gunter’s design offers tall walls and high-climbing steps, and Paul Pyant’s lighting throws huge and moody shadows. But that soon gives way to the bright and creamy court of the newly crowned Claudius (Tom Mannion) and his fresh bride, Gertrude (Imogen Stubbs, pictured top with Whishaw), widow of his brother, the deceased king.

This is a palace in modern dress with Champagne and tennis, Versace and rock’n’roll, secret service agents and Uzis. The language, too, feels new, spoken conversationally rather than declaimed, gaining enormously in clarity and losing nothing of Shakespeare’s gorgeous poetry and marvelous wit.

Nunn has cut the play so that it runs for 3 hours and 19 minutes with a 20-minute interval. He also, crucially, has placed Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” monologue 45 minutes into the play at a much more fitting moment than its typical place in the third act. Whishaw makes the scene his own and renders the contemplation of suicide, pills and Evian water at hand, with a teenager’s confusion over the romance and grisly reality of dying young.

Younger still, Samantha Whittaker defines Ophelia as a skittish teenager thrown into emotional chaos by the death of her father, Polonius (Nicholas Jones) and the escalating turmoil around her. Kevin Wathen and Edward Hughes play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as schoolboy innocents, pawns of Claudius and his minions, while Jotham Annan (pictured with Whishaw above) is stalwart as the prince’s loyal friend, Horatio.

Rory Kinnear makes Laertes a vigorously vengeful son, howling in his own grief over Polonius’ death and willing to be the instrument of Claudius’ murderous plans for Hamlet.

Mannion and Stubbs bring glamour and guile to their roles as some kind of Kennedys in an all too brief Camelot, and Jones hides his chief of staff’s cunning behind jovial bluster. James Simmons is strong in three roles, including a shrewd first player, as so is Sidney Livingstone, especially as the canny gravedigger.

Maggie Lunn’s casting is splendid throughout but Nunn must take the credit for melding them into a production that makes “Hamlet” fresh and relevant and gives the world a brand new star in Whishaw.

Venue: The Old Vic, runs through July 31; Cast: Ben Whishaw; Tom Mannion; Imogen Stubbs; Nicholas Jones; Rory Kinnear; Samantha Whittaker; Jotham Annan; Kevin Wathen; Edward Hughes; Playwright: William Shakespeare; Director: Trevor Nunn; Design: John Gunter; Lighting: Paul Bryant; Composer: Steven Edis; Sound: Fergus O’Hare; Associate Costume Designer: Mark Bouman; Fight director: Malcolm Ranson; Movement: Kate Flatt; Casting: Maggie Lunn; Voice: Patsy Rodenburg; Presented by Old Vic Productions, Ron Kastner and Background.

This review appeared in The Hollywood Reporter.

By Ray Bennett

LONDON – “The Holy Terror” is neither holy nor a terror although it is wholly terrible, being partly a satirical blast at book publishing that misfires on all cylinders and partly a dissection of a man’s descent into paranoia and madness that doesn’t bear scrutiny.

It’s difficult to imagine why writer Simon Gray wished to so completely revise his 1987 play, “Melon,” that starred Alan Bates and was quite well received when its targets appear already dated. You don’t have to know much about British publishing of the 1980s to suspect that Thatcherite era of greed to be one of ruthless excess. Mystifyingly, Gray sets up his play in the form of a speech by ex-publishing wizard Mark Melon to a meeting of the Chicester or Cheltenham, he’s not sure which, Women’s Institute. We then see episodes of his rise and fall as it were in flashback but the device serves no purpose other than to provide a quick fade for each scene.

It’s difficult to imagine why writer Simon Gray wished to so completely revise his 1987 play, “Melon,” that starred Alan Bates and was quite well received when its targets appear already dated. You don’t have to know much about British publishing of the 1980s to suspect that Thatcherite era of greed to be one of ruthless excess. Mystifyingly, Gray sets up his play in the form of a speech by ex-publishing wizard Mark Melon to a meeting of the Chicester or Cheltenham, he’s not sure which, Women’s Institute. We then see episodes of his rise and fall as it were in flashback but the device serves no purpose other than to provide a quick fade for each scene.

Simon Callow (pictured) plays Melon and his miscasting is evident quickly as this personable actor who has so well established himself as a jolly bachelor uncle is asked to play a sleek shark in the deadly shallows of publishing. In business, Melon tells the gathered ladies, “I knew not only whom to fire but how, which meant quickly.”

Melon throws himself into the task of ridiculing the old-time publishing chief (Robin Soans) and cutting to the quick his roster of writers. They strive mightily but fail miserably to be amusing, from an oddball from the Highlands whose prose is in some weird Scottish patois to the predictable housewife author of erotica to a bland lister of lists who turns his hand to a treatise on masturbation.

Melon not only “bonks” the office poppets and seduces the female writers but tries to entertain the Women’s Institute by making “bonking” out to be an onomatopoeia, so lame are the jokes.

By the second act, Melon has carved his way to the top and the only way to go is down. Being a ceaseless cheat himself, he develops the irrational belief that his faithful wife has been cheating on him. This becomes an obsession to the point that it drives him into therapy and finally electric shock.

The last part of the play is devoted to Melon’s assorted treatments and increasingly hysterical encounters with his doctors and bewildered wife. If the psychiatric scenes were not so stridently unfunny, Melon’s fate might engender some sympathy but even Callow cannot generate any. It all goes to his blameless wife Kate, endearingly played by Geraldine Alexander, who remains safely above the fray.

As the play careers into disarray, Callow appears to redouble his efforts to save it, dancing, chortling, and hurling himself to the floor. He becomes so red-faced and sweaty that you fear for his own health rather than anything that happens to Melon. It’s a shame that such a big-hearted performance is wasted on such a trying piece of work.

Venue: Duke of York’s Theatre, runs through Aug. 7; Cast: Simon Callow, Robin Soans, Lydia Fox, Tom Beard, Matt Canavan, Beverley Klein, Geraldine Alexander; Playwright: Simon Gray; Director: Laurence Boswell; Design: Es Devlin; Lighting: Adam Silverman; Music: Simon Bass; Sound: Fergus O’Hare. Presented by Theatre Royal Brighton Productions, Laurence Boswell Productions, Richmond Theatre Productions and Ambassador Theatre Group.

This review appeared in The Hollywood Reporter.

By Ray Bennett

LONDON – David Mamet seems like he would be the kind of scholarly poker player who, when someone hauls in a big pot through intuition and luck, chides the player for staying in with that hand.

Mamet writes clever and thought-provoking plays and he stacks the deck cheerfully, using his knowledge of feints, bluffs and tells to keep his audience off-balance. In “Oleanna,” the set-up is seven-card stud with one Queen wild.

The early cards suggest an everyday encounter between a confused young student and a caring professor. Carol (Julia Stiles) comes to the teacher’s study to beg for help. She says she doesn’t understand anything, not the book he wrote and nothing in his class. “I don’t know what it means and I’m failing. I’m stupid,” she says, sobbing.

John (Aaron Eckhart) is distracted by phone calls from his wife as they are in the middle of buying a new home. He’s up for tenure and his career is going well. He teaches education and he has all the confidence and arrogance of a successful middle-class male.

He hardly sees the condescension in the way he tries to mollify his student as he promises to tear up her marks, urges her to visit him again in his study, and steadies her shoulders as she sobs.

But then Mamet ups the ante and the wild Queen shows up. Carol accuses the professor of everything from elitism to sexism to sexual harassment. John stands to lose not only his shot at tenure but also his house and his job.

Here, the playwright uses cards that shouldn’t be on the table, however, as it’s inconceivable that a male teacher once accused of improper behavior by a female student would ever again be alone with her. But Mamet wants to build the pot and if Carol and John are to go head-to-head, they need private confrontations.

The play builds to a clash that when it was first produced in the early ’90s caused audiences to yell out at the actors and led to fierce male/female arguments afterwards. Mamet’s craftsmanship is so good, however, that the tone of the play is very much in the hands of director and actors.

Here, director Lindsay Posner takes the middle road and inclines to neither side. Julia Stiles is completely convincing as Carol as she emerges from dowdy submissiveness in the first act to great authority later when she quotes from the copious notes she’s taken and invokes the power of the group that supports her. Aaron Eckhart plays the first act in a very easygoing manner and it’s only as the conflict builds that it becomes apparent how subtle and detailed his earlier work is.

If “Oleanna” ends up more as a conversation piece than anything deeply involving it has to do with the mechanical way Mamet uses words. He gives his actors half-words and staccato syllables and expects them to sound as if they’re arguing, but the sound is of rhetoric, not two people engaging. They repeat phrases such as “Do you see?” that seek no answer. They talk a lot without saying much. At times you wish someone would simply tell them to shut up and deal.

Venue: Garrick Theatre, runs through July 17; Cast: Aaron Eckhart, Julia Stiles; Playwright: David Mamet; Director: Lindsay Posner; Designer: Christopher Oram; Lighting designer: Howard Harrison; Sound designer: Mic Pool; Costume supervisor: Sue Coates; Presented by Edward Snape for Fiery Angel Ltd., Clare Lawrence and Anna Waterhouse for Out of the Blue Productions, Broadway Partners by arrangement with Really Useful Theatres.

This review appeared in The Hollywood Reporter.

By Ray Bennett

LONDON – From the moment wealthy young Louis Trevelyan sits down with Sir Marmaduke Rowley, governor of the Mandarin Islands, to negotiate his betrothal to Rowley’s beautiful and spirited daughter Emily, two things are obvious: They are made for each other, and it can’t last.

Something else is soon clear too. “He Knew He Was Right” is comfort television of the highest order; intelligent drama, well acted with crisp dialogue and all the ingredients required for a period piece. There are horses and carriages on crunching driveways; languorous English country gardens; rubicund gentlemen in muttonchops and weskits; stout matrons in bonnets and frowns; and the most handsome young men and women struggling to find their place within the formalities of Victorian life.

Anthony Trollope’s 930-page 1869 novel has been adapted into four hour-long episodes by the prolific Andrew Davies, whose television work includes the miniseries “Pride and Prejudice,” “Vanity Fair,” “Dr. Zhivago” and one based on Trollope’s “The Way We Live Now.”

Davies benefits hugely from Trollope’s style of writing, which as well as being extraordinarily well crafted is also painstakingly detailed. No reader of Trollope is ever in doubt as to a character’s mood or meaning; no action is unexplained. The “he” who knew he was right in the title is rich young Louis (Oliver Dimsdale) who becomes convinced that his lovely wife Emily (Laura Fraser) has behaved in an unseemly manner with one Col. Osborne (Bill Nighy), a bachelor gentleman of middle years known to enjoy making mischief with married ladies.

All that has happened is that Col. Osborne, who is a friend of her father and her own godfather, has called upon Emily, and enjoyed innocent conversation with her. But news of his visits becomes known in London society and soon Louis becomes outraged even though he accepts not the slightest impropriety has occurred.

Still, in Victorian England, the husband has the right to impose his will and he demands that Emily apologizes and never willingly sees Osborne again. She promises obedience but knowing she has done nothing wrong, declines to say that she has.

On this trifling difference, Trollope hangs a plot that allows him to explore universal issues of love and trust, fear and madness and the impositions of a rigidly stratified society. For, as Louis banishes Emily and their son to increasingly impecunious shelter, he shrinks from his well-mannered life, eventually kidnapping his son to flee to a hideaway in Florence.

Meanwhile, the subplots are many and various and they all serve to amplify the central question of women rebelling against the Victorian notion that they are chattel. Emily’s sister Nora (Christina Cole) must choose between proposals from a lord and a penniless journalist named Hugh (Stephen Campbell Moore), whose sister Dorothy (Caroline Martin) similarly is caught between a vain cleric and a handsome young heir.

Davies limns all these characters expertly, often having them address the camera directly in order to speed the exposition along. They are rich characters, too, Dickensian in their particularity, especially the erratically strict Aunt Jemima (Anna Massey), the ruefully flirtatious Reverend Gibson (David Tennant), and the determinedly upstanding but ineffably seedy private eye Mr. Bozzle (Ron Cook).

As Louis, Dimsdale, who played Shelley in last year’s “Byron,” has the convincingly haunted look of the gifted early dead, and Fraser, who was outstanding in the film “16 Years of Alcohol,” never lets her loveliness mask the confusion, heartache and rage inside Emily.

Produced handsomely by Nigel Stafford-Clark and directed winningly by Tom Vaughan, ”He Knew He Was Right” is another triumph for writer Davies and all the bookstores that inevitably will have a major run on Trollope.

Airs: April 18, 25, May 2, 9 BBC1; Cast: Oliver Dimsdale, Laura Fraser, Christina Cole, Stephen Campbell Moore, Bill Nighy, Anna Massey, Goffrey Palmer, Geraldine James, John Alderton, David Tennant, Caroline Martin, Claudie Blakley, Fenella Woolgar, Ron Cook; Producer: Nigel Stafford-Clark; Director: Tom Vaughan; Screenplay: Andrew Davies, adapted from the novel by Anthony Trollope; Executive producers for the BBC: Sally Haynes, Bill Boyes, Laura Mackie; Executive producer for WGBH: Rebecca Eaton; Director of photography: Mike Eley; Production designer: Gerry Scott; Composer: Debbie Wiseman; Costume designer: Andrea Galer; A BBC Wales/WGBH Boston co-production in association with Deep Indigo.

This review appeared in The Hollywood Reporter.

By Ray Bennett

Following a much publicized Broadway run, it is testament to the power of Edward Albee’s play “The Goat, or, Who is Sylvia?” and the conviction of this Almeida Theatre staging of it that the central character’s declaration that he has fallen in love with a goat retains the power to shock.

It says much too of the fine acting of Jonathan Pryce as the man in question and Kate Fahy as his understandably distraught wife. Few playwrights have captured the art of marital warfare as insightfully as the author of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” nor as wittily.

To take a sophisticated, cultured and hitherto happy couple and drop on them the one thing no husband and wife might reasonably expect takes nerve and a very steady hand. Albee has both and the sudden introduction of bestiality into a formerly happy home is both devastating and hilarious.

Had it been in “Monty Python,” Graham Chapman’s military censor might have yanked it as being “too silly,” but whereas the Pythons would have had their Billy Goat jokes and moved on to something completely different, Albee takes full advantage of the opportunity it provides to lay bare conventions, assumptions and a bizarre taste for the barnyard.

Inevitably, the jokes are wonderful and Pryce and Fahy render them delightfully but Albee’s getting at serious things here too and both performers are more than up to it. There’s good work also from Matthew Marsh as their friend Ross and Eddie Redmayne as their gay son Billy. Anthony Page’s direction is firm and direct, making excellent use of Hildegard Bechtler’s impressive Manhattan apartment setting.

Martin, the goat fancier, is facing his 50th birthday and a candid television interview on his successful career as an architect, but he fears his memory is going. Not for nothing does Albee make him a designer of the city of the future and then have him discover the second love of his life amid livestock out in the countryside.

At first, his wife is pleased to think that this Sylvia is at least not someone she knows and even when it begins to sink in that Sylvia has four legs and a beard, she’s relieved that she learned of it from a friend and not the NSPCA.

But Albee makes sure we know how much this woman loved this man. She didn’t fall in love with him, she says, she “rose to love him.” And even as the illusions crumble and the furniture starts to crash, each of them is likely to pause to admire the other’s delivery of cut or thrust. “That was good, by the way,” they’ll say after a sharp line. It’s Albee’s reminder that humor is almost always the only remaining lifeline. They know the price of their sophistication, however. “I wish you were stupid,” she says. “I wish you were stupid too,” he replies.

But they’re not and Albee doesn’t shrink from depicting the pain of unimagined hurt as they realize that something has broken that cannot be fixed. The point is that there’s no protection against the unexpected except to keep going. In “Monty Python” no one expected the Spanish Inquisition or a giant pig to land on them. It could just as well be a goat.

Credits: Playwright: Edward Albee; Director: Anthony Page; Design: Hildegard Bechtler; Lighting: Peter Mumford; Sound: Matthew Berry. Cast: Stevie: Kate Fahy; Martin: Jonathan Pryce; Ross: Matthew Marsh; Billy: Eddie Redmayne.

This review appeared in The Hollywood Reporter

By Ray Bennett

LONDON – A great joke is recycled to very funny effect at the start of this engaging zombie movie spoof. In “Love at First Bite” in 1979, George Hamilton fetched up in full Dracula regalia on the streets of nighttime Manhattan to the complete and utter disregard of the locals.

Here, agreeable slacker Shaun (Simon Pegg), wanders about his North London neighborhood after the pubs close at night and first thing in the morning completely oblivious to the fact that he’s strolling amidst the living dead.

Outside of the slick Richard Curtis school of Hugh Grant humor and television’s “The Office,” British comedy is in dire straights these days and so Pegg, who co-scripted this clever and well-crafted movie is a major find.

There are certainly touches that only the homegrown crowd will get but there’s sufficient energy and scattershot horror movie references that it should please fans of gross-out humor everywhere.

Shaun is a no-hoper content with his job at a high street electronics store and nights at the Winchester Pub with girlfriend Liz (Kate Ashfield) and best mate Ed (Nick Frost). He’s full of promises, however, even if he forgets to book a table for a romantic dinner with Liz and overlooks his mum’s birthday.

But when the streets of London do begin to crowd with bloody and sometimes limbless zombies, Shaun is quick to act. Learning from the television news that only removing the head or brain will render a zombie harmless, he sets off with cricket bat in hand to rescue all his loved ones. Ed trundles along with a shovel but being the tiresome staple of British comedy, the fat stupid friend, it’s his job to prang the car, make too much noise, and generally put everyone in harm’s way.

Pegg and co-writer and director Edgar Wright keep their eyes firmly on the ball to follow the absurd logic of a genuine zombie film so that it becomes essential to gather a small crowd that includes the reliably amusing Dylan Moran and Lucy Davis (pictured above on either side of Ashfield and Pegg) in a place that can be defended. Inevitably, that means the Winchester Pub and the setting offers Shaun and Ed lots of means in which to combine two key goals: killing zombies and drinking beer.

There are clever gags along the way, including a very nice bit with Bill Nighy (“Love Actually”) as Shaun’s stepfather, who’s been bitten by a zombie. “It’s all right,” he says confidently. “I ran it under the cold tap.”

In a very funny sequence, Shaun and Ed try whipping vinyl record albums at the walking corpses, prompting a discussion of what albums can be sacrificed, such as the soundtrack to “Batman.”

One of the problems of recent British comedies has been that they run out of steam early. This one gains pace pleasingly and unsentimentally adheres to the horror film convention of losing popular characters along the way. “It’s been a funny sort of day, hasn’t it,” says Shaun’s mum (Penelope Wilton) just before she succumbs to a zombie’s bite.

It’s worth sticking around for the coda too, as it contains some hilarious and very politically incorrect suggestions as to how zombies might be put to work once they’ve been tamed.

Opens: UK: April 9 / US: Sept. 24 (Universal); Cast: Simon Pegg, Kate Ashfield, Nick Frost, Lucy Davis, Dylan Moran, Penelope Wilton, Bill Nighy; Director: Edgar Wright; Writers: Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright; Director of photography: David M. Dunlap; Production designer: Marcus Rowland; Music: Daniel Mudford; Editor: Chris Dickens; Costume designer: Anne Hardinge; Executive producers: Tim Bevan; Eric Fellner; Natascha Wharton; James Wilson; Alison Owen; Production: WT2 Production in association with Big Talk Productions presented by Universal Pictures, StudioCanal and Working Title Films; Rated: UK: 15 / US: R; running time, 99 minutes.

This review appeared in The Hollywood Reporter.