By Ray Bennett

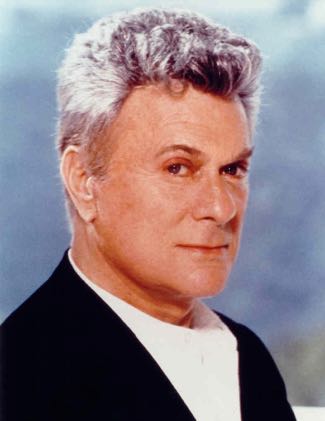

LONDON – Nobody loved being a movie star more than Tony Curtis, who was born on this day 100 years ago and who died in 2010, and as he got older he liked nothing more than to talk about it. “Don’t I have great stories?” he said to me. “Don’t you fucking love it?”

Curtis did an hilarious impression of Cary Grant to seduce Marilyn Monroe (pictured below) in “Some Like it Hot” (1959) but he told me that when director Billy Wilder screened the film for him, Grant said, “I don’t talk like that”, and Curtis said it just as Grant would have. They had starred together in the Blake Edwards war comedy “Operation Petticoat”.

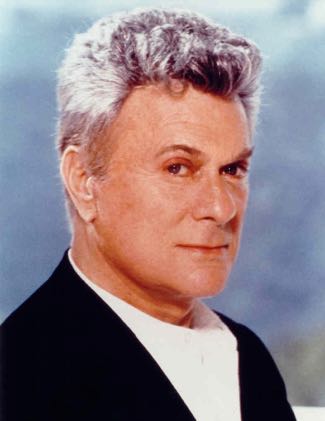

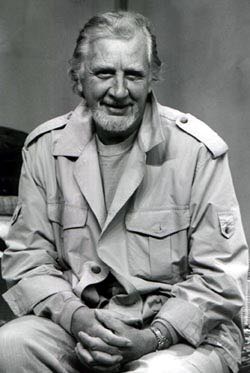

I spoke to the star of films such as “Sweet Smell of Success” (1957), “Operation Petticoat” (1959), “Spartacus” (1960), “Taras Bulba” (1962), “The Great Race” (1965), and TV’s “The Persuaders” at the Flanders International Film Festival on Oct. 18 2003 in Gent, Belgium, where he received a special Joseph Plateau Holemans Award for lifetime achievement.

Curtis appeared chipper and he was happy to chat about his life and career although, at 78, he said he wasn’t that interested in making more films: “I don’t want to grow old on the screen. I don’t want to play doctors and judges and lawyers, grandfathers and grandmothers, surgeons. I really don’t. I find living such an interesting experience. I don’t believe in ‘seniors’ or ‘juniors’.”

Born Bernard Schwartz in the Bronx, NY, of Hungarian Jewish immigrants, he still hadn’t lost the accent fully but he said he always wanted to be a movie star: “Ray, when I was a kid, I decided I wanted to be in movies. I’d go to the movies and see those images, those shadows, I’d say, ‘Jesus Christ, that’s for me.’ So what did I do? I started to jump on the back of trolley cars, jump on the back of taxicabs, climb up the trestles of the subway, climb up walls, chain link fences, jump from one roof to another, we’d put mattresses there.”

Curtis had no formal education in acting but he was a good athlete and he tackled life like an obstacle course: “Everything is an obstacle course. Being in the movies, I know my distance from you to here. I know where the mike is. I know the table lamp. I know everybody moving around me. I catch everything. It’s becoming aware of life, don’t you see? And that helps you in whatever profession you choose. By watching everything, it helped me as a painter, as a psychologist – as a person who reads other people and can read myself.”

Curtis had no formal education in acting but he was a good athlete and he tackled life like an obstacle course: “Everything is an obstacle course. Being in the movies, I know my distance from you to here. I know where the mike is. I know the table lamp. I know everybody moving around me. I catch everything. It’s becoming aware of life, don’t you see? And that helps you in whatever profession you choose. By watching everything, it helped me as a painter, as a psychologist – as a person who reads other people and can read myself.”

To have had his career gave him a great deal of pleasure, he said, and it was a joy to be who he was: “I’m so fucking privileged. I started out – this is not a Horatio Alger story, ok? To have done what I’ve done in my life is really appealing to me. I don’t think of it as some great accomplishment. In an odd way, I expected it. I knew I was going to make it in the movies. I knew I was a handsome kid. I knew I could get all the girls I wanted. I knew I could jump and learn how to swim and fence, dive, ride horses.”

He always preferred physical acting to the kind that depended upon expressing emotion: “For me, an actor’s strength is in his movement and not in his emotional madnesses. You’re jerking off in Macy’s window when you’re playing those parts and your excitement, or your action, is getting angry. Anybody can do that. That isn’t action, that’s just a mental attitude about yourself.”

There was never a movie he made that he demeaned or looked down on: “Nothing. I did a movie called ‘The Lobster Man From Mars’. The special effects were the worst. It’s still very difficult for me to eat lobster in a restaurant, though.”

He made two early pictures with “Singin’ in the Rain” star Donald O’Connor including “Francis the Talking Mule” (1950), and he said they became great friends: “I loved him. What a guy he was. What a brilliant, brilliant dancer. You saw what he danced like? How the fuck he never ended up one of the great dancers … I’ll tell you why, because he worked at Universal Studios, like I did. Had they given him the opportunity, he would have danced with every one of the great ones.”

O’Connor danced as well as Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly, Curtis said, “And he was an excellent boxer, the kindest, sweetest man. I’d go out to visit him at his house in the Valley where he had an 8mm movie projector. He’d put on a porno movie and shoot it out the window onto the garage door across the street. People would drive by and go, ‘What, what?’ and then he’d shut it off. That was my pal. I had a lot of fun with those guys.”

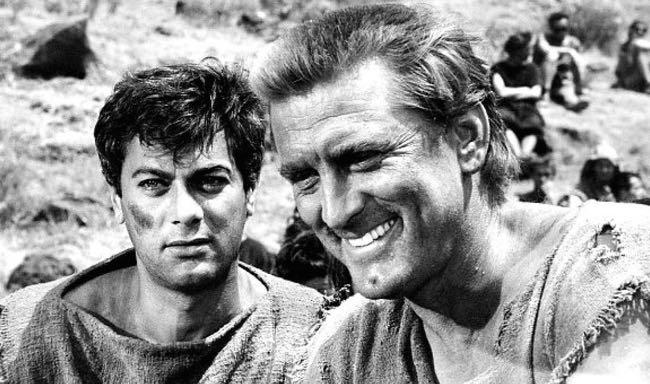

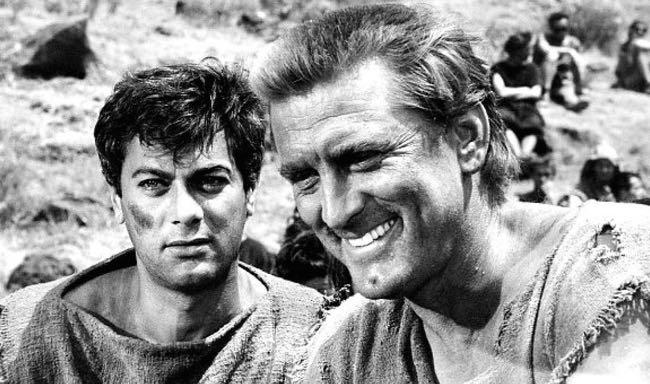

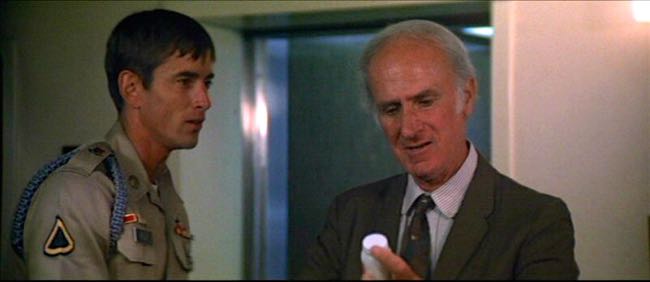

Curtis spoke of his “Some Like it Hot” co-star, Jack Lemmon – “What a man he was; what a life we had together. Cary Grant. Burt Lancaster, Gregory Peck.” But when it came to Kirk Douglas, not so much. They made “The Vikings” (1958), “Spartacus” (pictured below) and “The List of Adrian Messenger” (1963) together.

“He’s the only actor that I found more difficult to be around, more neurotic, let’s say. And that’s not a negative,” Curtis said. “He’s an excellent picture-maker. Boy, he sure knows how to get his picture made. He knows exactly how to delineate it; where to put the energy. But every picture he makes is a Kirk Douglas movie, all the rest of us are minor players. I’ll give you a good example, if I may. ‘Spartacus’, OK? Who gave him those crewcut haircuts? Where did he get someone to give him a Beverly Hills crewcut haircut? All of us were fucking walking around looking like gorillas and he comes out with this haircut. I don’t know.”

Curtis had no illusions about the business of showbusiness: “Hey, my pal, there ain’t no such thing as a movie that doesn’t make money. There’s absolutely no movie in the world that doesn’t make money. The money they spend on making it, when they’re making it, is a deductible item. So, if it looks on paper that it cost $8 million, it really cost $950,000. That’s then. Now, that $950,000 that it costs to make, is nothing. You can’t even build a house for $950,000. And look at the money people make today. And how much they get for theatre tickets. What is it, 10 bucks a ticket? Can you fucking believe it? I was going to the movies when it was 25 cents. Ten bucks a ticket. Twelve bucks. It never catches up to itself, it’s always growing.

I told him that it was a revelation to me to discover that in terms of the big studios, it’s not about profit, it’s about revenue. He said: “Exactly. Look how clever you are, to say that. Those pictures made 50 years ago, if that picture shows on television one night and generates $432, that’s like going into somebody’s wallet and taking out $432 and leaving. How could a movie like that generate that kind of money 50 years later? Don’t you see? That’s why everybody wants to get into the movie business.”

Signed to Universal, Curtis had been in films for seven years before his big break came along. “I never got into pictures that were … well, they were all right but they were made in a hurry; there was no finesse to them; they didn’t try to get a really important director, or get some other actors. They were ‘B’ movies; that’s what we made at Universal. That made it difficult. But when I got ‘Trapeze’, that changed everything.”

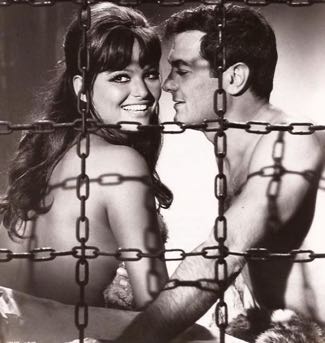

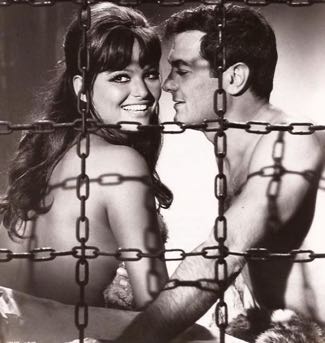

Curtis and Burt Lancaster played aerial performers opposite Gina Lollobrigida (pictured with Curtis above) in Carol Reed’s colourful “Trapeze” in 1956 and one year later they teamed again for Alexander Mackendrick’s highly acclaimed “Sweet Smell of Success”, which showed the world that Curtis was a fine actor as well as a movie star: “That catapulted me into the major player category. From then on in there wasn’t anything I could do that would be wrong.”

Curtis and Burt Lancaster played aerial performers opposite Gina Lollobrigida (pictured with Curtis above) in Carol Reed’s colourful “Trapeze” in 1956 and one year later they teamed again for Alexander Mackendrick’s highly acclaimed “Sweet Smell of Success”, which showed the world that Curtis was a fine actor as well as a movie star: “That catapulted me into the major player category. From then on in there wasn’t anything I could do that would be wrong.”

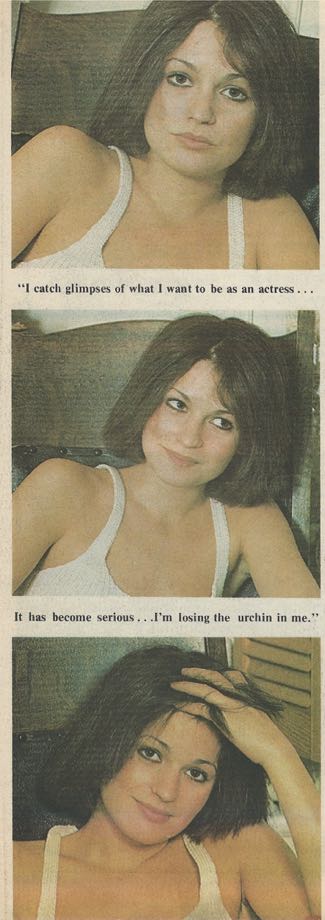

He made another picture with Mackendrick in 1967, an offbeat comedy titled “Don”t Make Waves”about the American Dream sixties’ style with Claudia Cardinale (pictured above left with Curtis) and Sharon Tate: “Now that was a very abstract movie, but he did it. He was a very brilliant man. Difficult to understand and very demanding of his work. Very domineering, you know. He wanted everything to work the way he wanted it. But look at the movies he made, ‘The Man in the White Suit’, ‘The Ladykillers’. Wow!”

Curtis said he modeled himself on Cary Grant more than just in “Some Like it Hot”: “Cary Grant, the most gracious man, extremely intelligent, very perceptive about life. I admired him a lot and I emulated a lot of him. Not in my behaviour so much but so much rubbed off on me. I’m a gentleman now. I’m very appreciative of people’s friendship. I like to be gallant. I like to kiss ladies’ hands. All these little things that I felt Cary Grant did automatically, I decided I would do. Perhaps he learned it from somebody else, Noel Coward or somebody. And that’s the fun of it. It’s just fun. It’s not demeaning or difficult, or anything.”

We would have spoken longer but then Jeanne Moreau entered the hotel lobby and fans surrounded her with cameras. Curtis had appeared with her in Elia Kazan’s “The Last Tycoon” (1976), and he said, “Forgive me, I must say hello.”

Curtis made his way through the small crowd, not much taller than the petite French actress. He seemed so pleased to see her; she just smiled.

20 David Niven movies you should see

By Ray Bennett

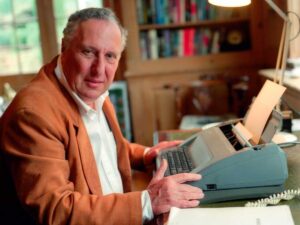

David Niven, who was born 115 years ago today and died aged 73 in 1983, gave Ron Base and me the best quote of all time.

The Oscar-winning British actor was on a book tour to promote his first memoir, the brilliant “The Moon’s a Balloon”, in 1972. Ron and I, who worked at The Windsor Star across the river, went to a Detroit hotel ballroom for a lunch – a hospital fundraiser – at which Niven was to speak. We were told we could interview him afterwards.

Lunch was great because we sat at a table with actress Constance Towers so we encouraged her to share yarns of her films with John Ford. Niven was a masterful raconteur and he spun hilarious tales from his book.

Always one of my favourite screen actors, Niven was the definition of suave and debonair from his start in comedies such as “Thank You, Jeeves” (1936), in which he naturally played Bertie Wooster (pictured above with Virginia Field and Arthur Treacher as Jeeves), and war pictures such as “Dawn Patrol” (1938).

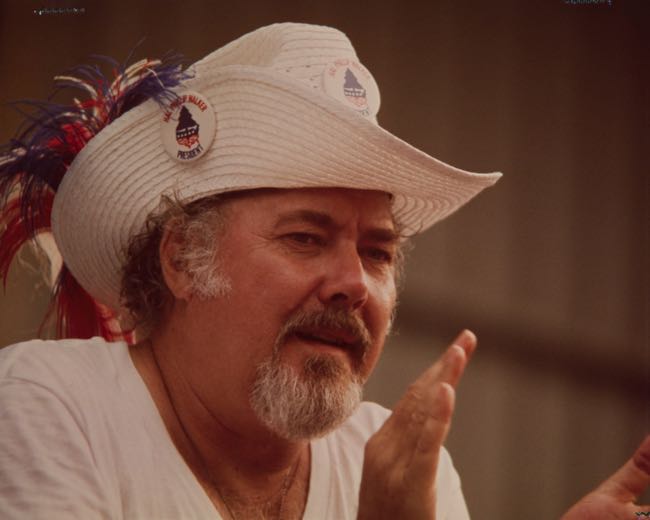

He might be best known for his role as Phileas Fogg in “Around the World in Eighty Days”, which won five Academy Awards in 1957 including Best Picture. He is perfect and Shirley MacLaine and Robert Newton (pictured below) have their moments although the film is a bloated travelogue stuffed with odd star cameos.

Here are 20 other David Niven movies worth watching:

“The Sea Wolves” (1980) Great fun based on a true story as Gregory Peck, Niven and Roger Moore play former soldiers who are sent on a secret mission in World War II to destroy a Nazi ship based in neutral Goa. Andrew V. McLaglen directs Reginald Rose’s entertaining script with a cast that includes Trevor Howard and Patrick Macnee.

“Murder by Death” (1976) Neil Simon’s Agatha Christie spoof has some wonderful moments from a cast in which Niven is joined by Eileen Brennan, Truman Capote, James Coco, Peter Falk, Alec Guinness, Peter Sellers and Maggie Smith.

“The Extraordinary Seaman” (1969) Bizarre comedy that I’ve always been fond of with Niven as the ghost of a drowned World War I sea captain who fetches up with his boat in World War II, helps some American sailors survive and falls for an American woman in the Phillipines. John Frankenheimer (“The Manchurian Candidate”) directs Faye Dunaway, Alan Alda, Mickey Rooney and Jack Carter.

“Lady L” (1965) Ambitious if flawed comedy directed by Peter Ustinov, who adapated a novel by Romain Gary about an ageing woman played by Sophia Loren who recalls the loves of her life. Niven, Paul Newman, Cecil Parker and Philippe Noiret are among them.

“The Bedtime Story” (1964) Comedy Marlon Brando and Niven as conmen who challenge each other to seduce women on the Côte d’Azur such as an heiress played by Shirley Jones. Bosley Crowther in the New York Times said the two actors hit “a comedy peak” and “it is a very funny picture. It was remade in 1988 as “Dirty Rotten Scoundrels” with Steve Martin, Michael Caine and Glenne Headley, and later became a successful stage play.

“The Pink Panther” (1963) Niven and Robert Wagner are the jewel thieves in pursuit of the fabulous gem worn by Claudia Cardinale (pictured above) although Peter Sellers steals every scene as Inspector Clouseau. Blake Edwards directs the first of the “Pink Panther” series, which he co-wrote with Maurice Richlin (“Operation Petticoat”, “Pillow Talk”). Henry Mancini, of course, wrote the infectious score.

“55 Days at Peking” (1963) Nicholas Ray epic about American soldiers and British diplomats in the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900. Niven stars with Charlton Heston, Ava Gardner and a very large cast with cinematography by the great Jack Hildyard (Oscar-winner for “The Bridge on the River Kwai”) and music by Dimitri Tiomkin (Oscar-winner for “High Noon”, “The High and the Mighty” and “The Old Man and the Sea”).

“The Best of Enemies” (1961) Smart and cynical comedy about a square-off in the Abyssinian desert in World War II between an Italian captain (Alberto Sordi) and a British major (Niven). Directed by Guy Hamilton (“Goldfinger”, “Funeral in Berlin”), it co-stars Michael Wilding and Harry Andrews atop a raft of British and Italian character actors.

“The Guns of Navarone” (pictured above, 1961) Grand wartime adventure directed by J. Lee Thompson and based on a novel by Alistair MacLean about a group of Allied soldiers who must destroy a giant Nazi cannon so that convoys at sea might remain safe. Niven stars with Gregory Peck, Stanley Baker, Anthony Quayle, James Darren, Irene Papas, Gia Scala, Richard Harris and Anthony Quinn, whom Peck told me was the greatest scene-stealer in the movies.

“Ask Any Girl” (1959) Frothy comedy about brothers who fall for the same woman although one doesn’t realise it. Shirley MacLaine stars with Niven and Gig Young (“They Shoot Horses, Don’t They”) with the late Rod Taylor also in the cast.

“Separate Tables” (1958) Niven was named best actor at the Academy Awards for his performance as a stiff British Army officer with a secret in Delbert Mann’s version of the Terence Rattigan play about a group of off-season residents of a middle-class hotel at the English seaside town of Bournemouth. Deborah Kerr (pictured above), Rita Hayworth, Burt Lancaster and Gladys Cooper co-star with Wendy Hiller, who won the Oscar for best supporting actress.

“Bonjour Tristesse” (1958) Saucy Otto Preminger story of an unconventional playboy (Niven) and his fetching daughter, played by Jean Seberg (pictured above). Deborah Kerr and Mylène Demongeot co-star in a film whose reputation has grown over the years.

“My Man Godfrey” (1957) Niven is a butler with a dubious past to an American family dominated by women played by such as June Allyson, Jessie Royce Landis, Eva Gabor and Martha Hyer. Henry Foster (“Harvey”) directs.

“The Way Ahead” (1944) Carol Reed (“The Third Man”) directs a morale-building drama written by Eric Ambler and Peter Ustinov about conscripts who learn about battle in North Africa. Niven stars with a raft of British character actors including Stanley Holloway (“My Fair Lady”), James Donald (“The Great Escape” and William Hartnell (the first Doctor Who).

“Spitfire” (1942) British actor Leslie Howard (“The Painted Desert”, “Gone With the Wind”) directs and stars as the airplane designer who created the famous machine flown by “the few” in the Battle of Britain in World War II. Niven, who left Hollywood to return to England for the war, co-stars with Rosamund John.

“Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife” (1938) Directed by Ernst Lubitsch from a screenplay by Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder adapted from a play by Alfred Savoir. Screwball comedy on the French Riviera with Claudette Colbert and Gary Cooper. Niven co-stars along with the incomparable Edward Everett Horton.

“Dodsworth” (1936) William Wyler’s screen version of the Sinclair Lewis novel about a US industrialist (Walter Huston) and his wife (Ruth Chatterton) who drift apart on a European holiday picked up six Oscar nominations. Niven co-stars along with Paul Lukas, Mary Astor and Maria Ouspenskaya.

“The Charge of the Light Brigade” (below, 1936) The famous tale directed by Michael Curtiz, who gave Niven the title of his second memoir along with other very funny English-language clangers, my favourite of which is when the exasperated director told Errol Flynn (who starred opposite Olivia de Havilland) and Niven: “You think I know fuck nothing, but I know fuck all!”