By Ray Bennett

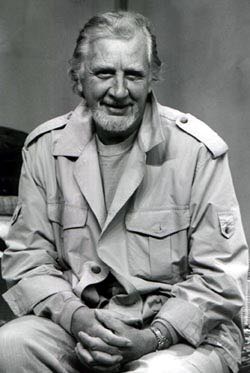

Argentinian composer Lalo Schifrin, who has died aged 93, is known for his concerts, recordings, film scores such as “Bullitt”, “Cool Hand Luke” and “Dirty Harry” and TV shows such as “Mission: Impossible” and “Mannix” but one of his most treasured works was for Carlos Saura’s Oscar-nominated musical “Tango”.

“I feel very proud of being involved in that movie,” Schifrin told me in 1998 just before the film had its international premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival.

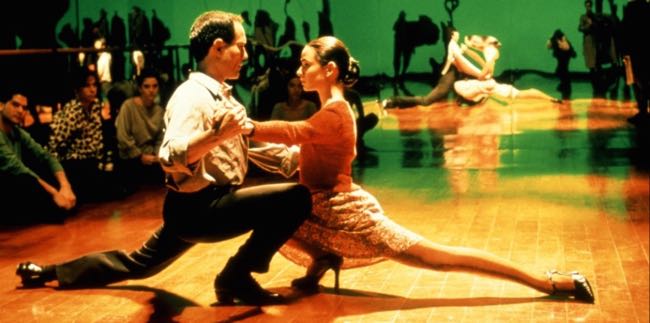

Directed by Carlos Saura and shot by three-time Academy Award-winning cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, “Tango” meant so much to the composer because of the way the film connected music and film to the terrifying period of dictatorship in his homeland.

During the years of repression in the Seventies when the military and Argentinian dictators were in power, they kidnapped people for any reason, he reminded me.

“It started as a civil war but then, like all these things, it got out of hand and the military became very fascistic and very brutal. Constitutional rights were finished,” he said. “They were torturing people and they were playing tangos very loud in order to cover up the screams of the victims. They used electric prods and any method of torture and they killed many people. They calculated that 40,000 to 50,000 people disappeared in that period. In the movie, there is a tango that I did with the Philharmonic Orchestra of Buenos Aires titled ‘The Repression’. It’s a very, very strong moment.”

He contributed around 45% of original music for “Tango”. Source music was used for the ballroom dance scenes but Schifrin supervised the orchestration of the traditional tangos and one titled ‘Calambre’ by Ástor Piazzolla, with whom he had performed: “I did the score in the rhythm of the tango. The movie is a musical without songs as Carlos tells the story through dance. It’s not a documentary; he tells a story through the tango.”

He contributed around 45% of original music for “Tango”. Source music was used for the ballroom dance scenes but Schifrin supervised the orchestration of the traditional tangos and one titled ‘Calambre’ by Ástor Piazzolla, with whom he had performed: “I did the score in the rhythm of the tango. The movie is a musical without songs as Carlos tells the story through dance. It’s not a documentary; he tells a story through the tango.”

Schifrin explained that what happened to tango music in that period in Argentina was similar to the swing era when bands led by Glenn Miller, Harry James, Artie Shaw and Duke Ellington were popular: “They were playing for dance but they sounded different. The same thing happened in Argentina for tangos. Each one of the bands had a style. Some of the arrangements we could retrieve but very few. The others had to be reconstructed from records. I had to supervise the hiring of different orchestrators and ensure that the arrangements were exactly the same style as those orchestras.”

He recorded the score in Buenos Aires, he said, because the best tango musicians were there: “I used very good soloists, in comparison, going back to jazz, with Charlie Parker. I had the best bandoneon player, Nestor Marconi. That’s the instrument that Piazzola played. It’s a concertina but it’s big and very difficult to play. It was invented in Germany in the 16th century. In poor churches, they couldn’t afford an organ so they had a portable bandoneon. I had some of the best violin players, all-stars. There’s a pianist named Horatio Salgan who is like an Argentinian Oscar Peterson. He’s 80 years-old and he not only plays but he appears in the movie.”

Schifrin’s musical reputation reaches far beyond Hollywood. Born in Buenos Aires into a musical family, he received classical training there and in Paris and then ventured into jazz in Europe and South America. He performed with Piazzolla and later Dizzy Gillespie, Xavier Cugat and Johnny Hodges. His own works range from concert music to jazz and he has recorded with artists ranging from Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan to Placido Domingo and Julia Migenes.

Schifrin’s musical reputation reaches far beyond Hollywood. Born in Buenos Aires into a musical family, he received classical training there and in Paris and then ventured into jazz in Europe and South America. He performed with Piazzolla and later Dizzy Gillespie, Xavier Cugat and Johnny Hodges. His own works range from concert music to jazz and he has recorded with artists ranging from Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan to Placido Domingo and Julia Migenes.

He has written many commissioned works and arrangements for orchestras around the world and for such events as the Three Tenors World Cup celebrations in Rome, Paris and Los Angeles. In 1996, he arranged and conducted a major concert in France to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the first cinema images by the Lumiere Brothers. Some of the tree-hour concert is available on a CD titled “Film Classics”.

With four Grammy Awards and six Oscar nominations to his credit, many of Schifrin’s recordings are available on his wife Donna Schifrin’s record label, Aleph Records, and via his own website.

He chooses not to name a favourite: “I like all of them because it’s like asking a father which of his children he likes better.”

He chooses not to name a favourite: “I like all of them because it’s like asking a father which of his children he likes better.”

Schifrin also declines to categorise film music. He told me, “In the whole history of talkies, since sound started in movies, you cannot talk about the state of the art in terms of music because it changes according to the movie and the composer and the style. Sometimes B-movies have great music, so it depends. I don’t think you’ll ever be able to make a generalisation because movies have one aspect that is artistic and the other aspect is industrial. It is an industry and because of that, it depends on fads – wide lapels, you know? Basically, the composers who have personality, they do what they do. Bernard Herrmann, when he did ‘Psycho’, he was not going by fads, he was inventing things. The best composers are the ones who try to make a contribution by inventing things.”

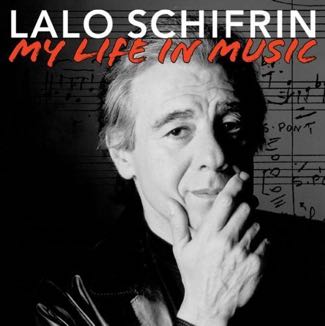

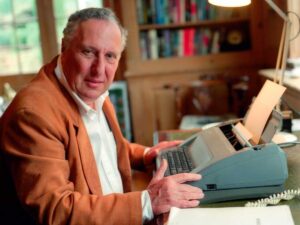

The photo of Lalo Schifrin at the top was taken when he was awarded BMI’s Max Steiner Film Music Achievement Award for his outstanding contributions to film music at the Wiener Konzerthaus in Vienna on October 22, 2012. Afterwards, David Newman conducted the Vienna Radio-Symphony Orchestra in a selection of Schifrin’s compositions during the annual Hollywood in Vienna Concert, which celebrates classic and current masterpieces of film music.

TV broadcaster Bill Moyers regarded the elite as the enemy

Veteran TV newsman Bill Moyers, former New York Newsday publisher and press secretary to President Lyndon Johnson, has died aged 91. As a broadcaster, he often spun off bestselling books from his TV productions and in 1989 he produced a documentary series with accompanying book titled ‘A World of Ideas’. I did a phone interview with him about it for a short-lived national U.S. magazine called Inside Books. I admired Moyers greatly and I was extremely pleased after my story was published when he wrote to say: ‘I don’t know how you managed to get in so much detail so accurately from a phone interview but I am very impressed and grateful.’

Here’s the story:

Bill Moyers talks candidly with Ray Bennett

Bill Moyers has the well-deserved reputation of exploring important issues and themes on his PBS-TV programmes that the rest of television ignores. But don’t accues him of appealing to an elite audience. He doesn’t buy it.

His series ‘Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth’, he says, has been seen by thirty-four million viewers and the accompanying book spent more than forty weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. Rolling Stone magazine says it is the most popular book on college campuses.

His new book book, ‘A World of Ideas’, also is based on a TV series that aired last year. He has received thousands of letters in praise and gratitude from teachers and judges and from housewives, single mothers and prisoners.

‘The response suggests,’ Moyers says, ‘that it is not just a small slice of the American elite who are interested in those deep questions of life. There’s a large audience out there not satisfied with the tabloid TV and sensastionalism that has gripped us today. The American mind is not only open but it’s yearning for, and seeking, something else.’

If anything, he regards the elite as the enemy whether it’s television, politics or religion. He created ‘A World of Ideas’ – a series of interviewes with an extraordinary collection of scholars, historians, philosophers, artists, writers and activists – specifically to air during last year’s presidential elections.

‘So few voices get heard in a political campaign and on TV it means that tens of millions of people are at the mercy of the brain cells of a very limited and narrow circle,’ he says. ‘We’re at the mercy, in a political campaign, of a relatively small handful of media advisers, politicians, pundits and journalists who say, “This is what the issues are about and if you don’t agree with us then you’re outside the pale.’

He chose people – from the late historian Barbara Tuchman to author Tom Wolfe to pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton – who could illuminate issues he believed would be treated poorly in the campaign. The danger of following blindly one school of thought, he says, is everywhere.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s five-million dollar murder contract on British author Salmon Rushdie is a horrying example of what he means. ‘What the Ayatollahs and Jerry Falwells – because Christianity has its ayatollahs too – show us is the great danger of dogmatism, of the doctrine,’ he says. ‘That’s where the mind closes, when it’s told, “This is the truth and you will either accept it or die”.’

Moyers says he hopes the Rushdie affair will bring people up short and make them think about the intolerance of religious dogma. ‘What the Ayatollah’s contract on Rushdie says,’ he insists, ‘is that religious dogma can be blind, malicious and murderous when all the great scriptures suggest that God does not fear the truth.’

As he makes clear on every page of ‘A World of Ideas’, Moyers is passionate about freedom of speech. ‘Americans are not more intelligent, more virtuous or wiser than other peoples,’ he says. ‘What separates our society from others is our constitutional guarantee of free speech – the First Amendment. That means nobody may have a monopoly on the concersation of democracy. It enables us to crawl up onto the bridge of the ship, grab the captain by the arm, shake him and say, “That’s an iceberg out there”. It is the First Amendment that allows the lonely dissident to say, “Wait a minute, is that true? Is that right? Is that just?”’

Moyers has been hammering this theme since his first book, ‘Listening to America’, almost twenty years ago, His conclusion was that civilization is a thin veneer of cooperation above a seething ocean of conflict, self-interest, fear and chaos. It is a fragile crust, he suggests, that can be destroyed under the boot of ignorance, prejudice and meanness as easily as the crust of life on the surface of the planet.

He holds the media responsibile for two great sins that endanger the crust – consumerism and forgetfulness. Moyers has worked in commercial television (in two stints with CBS) and he says his counterparts there are decent people who want to be serious about their work and who know that television has a role to play in the quality of democracy.

‘And yet,’ he says, ‘out of a fear that the American people have no attention span they keep going deeper and deeper into sensational subjects and titilating stories that they think will arouse viewes for one more minute until the next commercial.’

Moyers believes TV producers can be divided into those who see Americans as a society of citizens and those who them only as consumers. ‘If you see them as consumers, you go at them trying to divest them of their money,’ he says. ‘If you see them as citizens, you go at them trying to empower them to act in the public interest.’

Television today has seen an explosion of chatter from talk shows to tabloid TV. Broadcasters insist they only give the people what they want. ‘What they’re really saying is that consumers will tell them what sells,’ says Moyers. ‘That’s the ethic at the heart of this mania over tabloid TV and sensationalism. Everyone’s out there to sell something. On TV in general, and in political campaigns in particular, ideas mean what you have to sell, what you have to hustle – the point of view, the product, the ideaology, the position paper.’

As a result, TV concentrates on what’s happening this very minute and forgets the past. ‘I worry greatly that we, as Americans, know everything about the last twenty-four hours and nothing about the last twenty-four years,’ he says. ‘The Iran/Contra scandal was as dangerous a breach of democratic ideals as has happened since Watergate and yet we’ve relegated it already to a footnote in history.’

He cites Czeslaw Milosz (the Polish writer who won the 1980 Nobel Peach prize for literature and now teaches at the University of California at Berkeley) who said this era has seen such a proliferation of mass media that sociery is characterised by a refusal to remember.

‘A refusal to remember. I think that’s a horrifying reality,’ Moyers says. ‘In Orwell’s “1984”, Big Brother says everything must be flushed down the memory hole and washed away into that vast sea of ignorance out there. What the Iran/Contra scandal showed was an administration that wanted to play tennis with the net down so that it could decide what was foul and what was fair.

‘By consigning Iran/Contra to a footnote, by flushing it down the memory hole, we are leaving ourselves at the mercy of rulers who will tell us what is important and what we should pay attention to. The press seizes upon the moment, forgetting yesterday.’

Still, Moyers, married with three grown children and a confessed movie nut, believes that talk can save the day. ‘I think of democracy, particularly our democracy, as a long-running conversation beginning back in the revolutionary days,’ he says. ‘We talked this nation into existence and we’ve been talking about America ever since.’

He views television as the heart of the global village that Marshall McLuhan defined where people will occasionally come together and sit around the campfire not just to stay warm but to hear the tales of the tribe. He says the response to his TV series and books shows that there are millions who recognise that education doesn’t end with a high-school diploma; that it’s only just begun with a college degree.

‘I look at television as the largest evening class ever offered the American people,’ he says. Paraphrasing Saul Bellow’s observation that adults who attend evening class are seeking culture only ostensibly; that they are really seeking common sense, clarity and truth, ‘People are dying for something real at the end of the day,’ he insists.

While Moyers has achieved his greatest success as a broadcaster, he is at heart a journalist. He worked on the newspaper in the small Texas town of Marshall when he was 15. His books include ‘The Secret Government: The Constitution in Crisis’, a powerful indictment of the Iran/Contra scandal published in 1988. Invariably, his books contain much more material than the television programmes that inspired them.

Betty Sue Flowers, of the University of Texas, who edited ‘A World of Ideas’, says, ‘Editing these 41 conversations was like participating sentence by sentence in a seminar on our changing American values and how they affect our lives in an increasingly global culture.’

Flowers edits from the raw tape of Moyers’s conversations, which often run longer than an hour but for TV are edited down to 24 minutes. Interview subjects also are invited to amend or add to their remarks and Moyers himself approves the final printed version. Readers, therefore, have a richer abundance of information than viewers of the TV version.

Moyers says he chooses his guests with an eye for both TV and print. ‘I read constantly,’ he says, ‘and I’m always running into ideas whose authors intrigue me.’

For years, he’s kept a file of fascinating people he’s encountered in print that he would like to have to dinner or spend a weekend with. ‘People have asked me what book would I most want to take on a desert island,’ he says. ‘I always say I wouldn’t take a book unless I could take the author too. I can’t read a good book without wanting to talk to that person, to find out what he or she means and explore ideas further.’